“My fear was that one day someone would tap me on the shoulder and tell me I didn’t belong. I felt this for nearly 20 years.”

Unrealistic standards. Fear of failure. Obsession with results. Crushing self-criticism. Lawyers are battling a dark side to their relentless pursuit of excellence.

Anjani Amriit had the kind of legal career that belongs in a movie. She worked for top-tier firms in both the United Kingdom and Australia, flying first class around the world to negotiate deals worth many millions of dollars as part of her thriving mergers and acquisitions practice. From the outside, she appeared to have it all. On the inside, however, it was a completely different story.

“It was a lot of pressure, with long hours and no life outside of work. I had low-level anxiety constantly, coupled with regular panic attacks,” she tells LSJ. “When I say regular, I mean daily. I would have to go to the bathroom and get myself together. I lost 19 kilos. I couldn’t eat because I was so anxious.”

Amriit describes herself as a perfectionist. It worked to her advantage through university and the early years of her career, helping her turn heads by consistently achieving high standards. She drove herself to work longer than everyone else, bill more than everyone else, and to always deliver the best results.

“My fear was that one day someone would tap me on the shoulder and tell me I didn’t belong. Every single day, I felt like every single thing was make or break. I felt this for nearly 20 years,” she says.

Problematic perfection

Perfectionism describes a pattern of thoughts in which a person strives to be flawless. It can present with a range of symptoms that typically includes scathing self-evaluations, intense fear of failure, controlling behaviours, uncompromising standards, and obsession with structures such as rules and lists.

This is an issue that resonates with many in the legal profession. Close to 1,700 NSW-based lawyers signed up for a recent webinar entitled Understanding and Managing Perfectionism, hosted by organisational psychologist Kristiina Bedford, which was held as part of the Law Society of NSW’s Staying Well in the Law series. Polls taken during the session revealed some interesting insights.

Nearly 70 per cent of respondents agreed they feel they must give 100 per cent on everything. A third said they “always” put off work until they feel they can get it “just right”. A third of participants also expressed dissatisfaction, agreeing that things they accomplish are never quite good enough.

“Perfectionism can enable us to achieve high performance and deliver high results,” Bedford said during the session. “The key message to take away is that managing perfectionism isn’t about lowering your standards, it’s about recognising where it can become unhelpful and where you can use your time more efficiently.”

According to Bedford, perfectionism can either be adaptive (healthy) or maladaptive (unhealthy).

Adaptive perfectionism means people are able to accept small failures, set realistic goals, manage stresses surrounding achievement, and use positive reinforcement to motivate themselves. In this context, it can be a helpful and empowering trait with high levels of self-esteem and wellbeing.

Maladaptive perfectionism, on the other hand, is characterised by high levels of self-criticism, being terrified of criticism, constantly perceiving underachievement, and being paralysed by the fear of making a mistake. This is accompanied by strong feelings of shame and guilt, and mental ill-health.

Anjani Amriit

Anjani Amriit

‘I couldn’t breathe’

Cassandra Kalpaxis is a family lawyer with her own practice in Parramatta. She’s currently working from home, juggling a busy caseload and homeschooling duties for her kids, aged five and seven. She tells LSJ starting her own firm four years ago was a chance to not just to build the life she wanted around her family commitments, but to create a positive culture with space to prioritise mental wellbeing.

“Perfectionism became an issue for me as a young lawyer, needing to impress my employers, needing to impress my colleagues, and putting pressure on myself to get everything right all the time,” she says. “Eventually I developed a panic disorder. I didn’t realise I suffered from anxiety until I was working in the city and I realised I couldn’t breathe. I thought it was normal because I was stressed, until I went to a doctor and they said it wasn’t normal to always feel so worried about the next thing.”

It was something she kept well hidden – a common trait among perfectionists, who are highly skilled at masking their true feelings. Kalpaxis says it’s linked to cultural issues that urgently need to change.

“The culture that exists among lawyers is that, ‘I need to be the smartest person in the room’, or ‘I need to be the best at everything’,” she says. “We should recognise the strengths in each individual and work collaboratively in that regard. We can’t all be the best at everything – that attitude is toxic.”

Behind the mask

Left unchecked, perfectionism can lead to issues such as depression, anxiety, and even self-harm.

Greg de Moore is an associate professor of psychiatry at Westmead Hospital in Sydney. He says problems arise when this type of thinking becomes obsessional, resulting in black-and-white rationale and emotional instability that comes as a by-product of keeping everything bottled up inside.

“Shame and obsessionality go hand-in-hand. That feeling of failure, of having not achieved, is something you don’t want to expose publicly. It’s often a reason for people feeling reticent to talk about it,” he says, explaining this makes it hard to identify potential issues before a major incident occurs.

“A lot of these things can be terribly draining and lead to serious psychiatric disorders … People can work for a long time – two, three, four years – developing depression with an apparent appearance of normalcy.”

Once it reaches a critical point, things can spiral quickly – de Moore gives LSJ an example from his recent practice, treating a solicitor who runs their own successful practice, fits into an upper-middle class demographic, has a range of other interests outside work, and appears to be very successful.

The first hint of a problem was a rising tide of anger that was gnawing away inside. The second hint was an obsession with a cliff edge located nearby – this lawyer would walk there regularly and began to seriously contemplate self-harm. This was the point at which they spoke to a friend and sought help.

“It’s common for people who are depressed to feel like there’s nothing anyone can do to help them,” de Moore says. “There’s also the fear – the stigma – of being maligned as mad or incompetent. But this person has done extraordinarily well. One of the things we talk about quite a lot is obsessional thinking – I’m not talking about OCD here, I’m talking about people who are preoccupied with perfecting every detail, who rationalise their behaviour a great deal. I see that a lot in the legal profession.”

Note on mediocrity

A classic retort de Moore gets all the time, which he says he’s heard from a number of lawyers when talking about perfectionism, is: “Aren’t you just saying that we have to accept mediocrity?”

“They get tied up in words and we end up going round and round in circles,” de Moore says. “We can certainly try hard to maintain standards, but if we accept our imperfections, it’s not mediocrity. It’s human. There’s a real fear around that. No-one is saying we don’t want people striving to do things extraordinarily well – but when it impacts your work, your relationships, it can cause meltdowns.”

Rachel Setti

Rachel Setti

“If you’re the sort of perfectionist who berates yourself over every slight, that’s an issue. You’re likely to see that kind of behavior leading to avoidance and not getting things done because the fear of failure can be crippling.”

Lawyers are famously high-achieving, not just in the course of their work, but their other pursuits. How many do you know who run marathons, write books, run side businesses, play music at virtuosic levels, or show artworks in exhibitions? Tim Wu, a professor of law at Columbia University in New York who now serves as an official in the Biden White House, published an essay on this topic for the New York Times in 2018. He argued, “the pursuit of excellence has infiltrated and corrupted the world of leisure”.

Wu’s hypothesis is that most people are reluctant to start hobbies because we’re afraid of being bad at them. We no longer run just to run, or paint just to paint – we’re always aiming for the next big thing. The result is a population divided between “semi-pro hobbyists” and those who lack the motivation to get started at all, opting to passively while away their time in front of screens. Demanding excellence in all pursuits robs us of the simple pleasure of doing things merely because you enjoy them.

Black hole of time

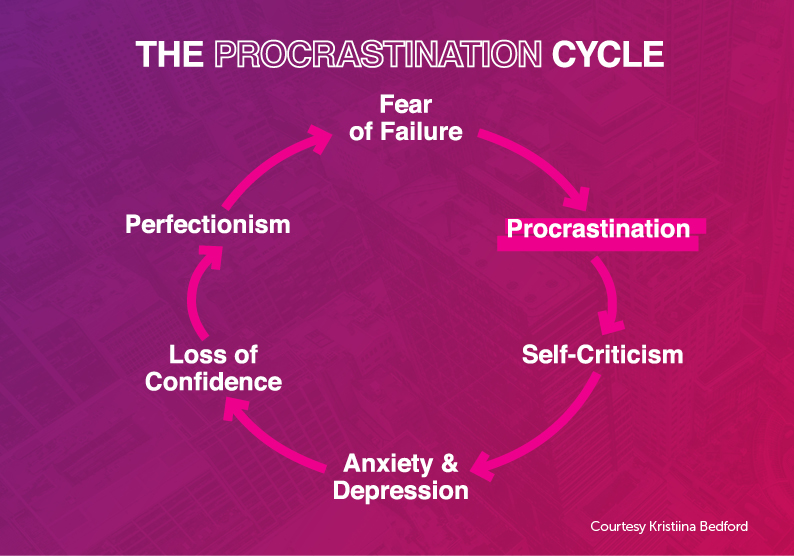

Procrastination is also a common trait amongst perfectionists, but it’s not to be confused with laziness.

“If you’re the sort of perfectionist who berates yourself over every slight, that’s an issue,” says Rachel Setti, an organisational psychologist.

“You’re likely to see that kind of behaviour leading to avoidance and not getting things done because the fear of failure can be crippling. It can actually become a self-fulfilling prophecy, leading to things like reduced productivity, slower turnaround times, low output, making promises you don’t keep, missing deadlines, et cetera. The smallest thing can lead to anxiety.”

Setti says there’s a significant body of research around the impact of pessimism in the workplace. It’s generally associated with poorer career outcomes – with the notable exception of the legal profession, where it’s critical to success. Lawyers are hired to not just resolve problems, but to anticipate potential problems before they arise. Although it’s a helpful trait professionally, it can cause problems personally.

“Most things are a combination of nature and nurture,” she says. “Given we can’t control nature, we have to look at nurture. Many people pick up perfectionistic tendencies, like inflexible thinking styles or catastrophising, from role models in their lives. The good news is that if you can learn to recognise this, you can work on reframing it. It’s really important to note that you can move on from perfectionism.”

However, Setti notes that understanding this on an intellectual level doesn’t necessarily mean it’s easy to put into practice. That’s where lawyers may benefit from the support of a mental health professional.

‘A bunch of self-doubt’

Stefanie Costi is a mature-age graduate who was admitted to the profession in February after swapping a media career for law. She says one of the challenges she’s encountered as a junior lawyer is taking a long time to do tasks because she wants to make them perfect for partners, while keeping a close eye on her billable hours.

“You’re constantly second guessing yourself. You know that you’re good at your job, but you’re also constantly thinking there’s someone who will take it if you don’t perform or you don’t make the budget,” she says. “It leads to a bunch of self-doubt. It’s a balancing act and it does lead to anxiety.”

Costi has learned that you have to know what you bring to the table and be confident in it. Some are traditionally book smart, some are great at thinking on their feet, some have great people skills. That’s where she excels – being able to read the room, read the client, read the partner, and respond.

“Perfection isn’t a buzzword, it’s something we use to torture ourselves,” she says. “I sometimes look at others and think, ‘What’s wrong with me? They’re doing it so much faster or so much better’. But with time as a lawyer, I’ve realised that I’m never going to know everything, and I’m never going to get everything right the first time I try it. Nobody is ever going to be perfect, we all have shortfalls.”

The path forward

In the end, Amriit walked away from law, travelling to India to find some perspective.

“I basically went to Eat, Pray, Love myself, before that book was written,” she laughs. “Over time, I was able to fully recover – mental health, physical health, emotional health, I realised that everything was an inside job. Nothing outside of us can help; we have to change from the inside out to recover our wellbeing.”

It took a while to find her next path, but she now runs her own business doing speaking engagements and corporate training, creating programs that empower leaders and build resilience. One of her goals is “helping lawyers stay lawyers” – by that, she means working through issues such as perfectionism to ensure people can work happily and healthily while avoiding career-ending burnouts.

“Once we let go of perfectionism, people feel more at peace, share more authentically, do way less work and achieve way more with our time,” she says.

“The main thing for people to understand is that we’re not meant to be perfect. We’re not infallible. We’re human, we make mistakes, and that’s OK.”