It is becoming increasingly clear that the pandemic we all hoped would be done and dusted by now is still in it’s early stages. So how is the legal profession, known for its issues surrounding mental health, tracking during the pandemic – and what can be done to safeguard wellbeing?

The COVID-19 pandemic is having a profound impact on the mental wellbeing of all Australians. From coping with changes to the way we work, a lack of social interactions and the challenges of home schooling, the new realities of life in 2020 are taking a lot of getting used to. Not to mention worries about the virus itself and uncertainty about what lies ahead – in terms of our employment prospects, finances and mobility.

For many legal practitioners, an average work day looks vastly different to just six months ago. Working from home is the norm, it’s harder than ever to switch off from work, and job instability is everywhere – all of which, experts say, could contribute to soaring rates of mental health problems in the months ahead.

Working from home

Since mid-March, many lawyers have been required to work from home, and instead of taking place in offices and boardrooms, much of the country’s legal work is now completed in home offices and on kitchen tables.

For many professionals, the opportunity to work from home is a welcome respite from long commutes and workplace politics, but Rachel Setti, an organisational psychologist and executive coach, says the arrangement can exacerbate the difficulties many lawyers experience maintaining a boundary between work life and personal life.

“Most lawyers I’ve worked with work a full day in the office, go home, take a couple of hours off and then log on again and do another half day’s work in the evening,” she says.

“Although most people dislike commuting to and from work, it does provide a time and space between the office and home. Working from home often means they don’t have that break, and that’s increasing the danger of burnout for some lawyers.”

And even though one of the perks of working from home can be more time with family, this arrangement can also contribute to stress.

“Home has become a bit of a pressure cooker,” says Beyond Blue’s lead clinical advisor, Dr Grant Blashki.

“People are suddenly working from home, perhaps with a partner who is also working from home, and they may have children who are at home, too. What used to be a relaxing space has now become a work space.”

Setti says living in shared housing can present similar challenges for junior lawyers.

“They’re not as likely to be living in homes where they have a home office or quiet part of the house to sit and focus and do their work,” she says.

“Junior lawyers are more likely to be living with other young people, and with less space.”

Change of pace

With much of the professional workforce working from home and many businesses closed or operating at reduced capacity, dramatic changes to the structure and pace of work are another source of stress and anxiety among legal professionals, says Emi Golding, Director of Psychology at the Workplace Mental Health Institute.

“Lawyers on average tend to measure higher on a scale of urgency than the general population,” she says. “They are used to and enjoy a fast-paced way of working and have established routines that work for them – and now that all has to be adapted.

“They might be doing video calls instead of meetings, which can take a bit longer, and there’s lots of other people that they may need to work with who might not be as available as usual to move things along.”

Dr Christopher Lennings, a clinical and forensic psychologist with expertise providing reports for courts, says one of the most significant challenges has been disruption to the day-to-day running of the legal system.

“The custodial system and the police system and the like have all come to a halt,” he says. “In some cases, there are problems being able to get evidence. There are problems getting witnesses. There are problems with judges not wanting to sit in open court. There are problems interviewing clients in jail.

“Having to work with different elements of the legal system that are not functioning properly and not being able to do the normal routines that are part of your legal practice increases stress and strain on lawyers.”

Coping with uncertainty

Along with where and how they work, many lawyers are struggling with the uncertainty of whether they will have enough work in the short and long term. In a recent survey by Hamilton Locke examining the impact of the pandemic on the mental health of legal professionals, half of respondents listed uncertainty as one of their biggest challenges. Uncertainty disrupts the way our brain anticipates and prepares by generating hundreds of possibilities and threats, which contributes to fear and anxiety.

“Busy professionals, particularly people in the legal profession, are often high achievers who like a sense of control over their environment,” says Golding. “And obviously there’s many aspects of the current situation that we’re not in control of, and that can definitely lead to more anxiety for people.”

Setti says the ongoing nature of the pandemic is the biggest challenge for lawyers. “It’s hard to ignore the question of how long staffing levels will be sustained at the level they are now, and concerns around future career and job security is most likely to be anxiety provoking,” she says.

Dr Lennings agrees: “If, for instance, lawyers were aware that there was going to be a period of shutdown for six weeks or eight weeks or 12 weeks then everything would spring back, people would take that in their stride, but that’s not what we’ve got. It’s the uncertainty about when it’s all going to end that fuels anxiety”.

You don’t get taught the skills and equipment you need to deal with failures, setbacks and not being in control. And that is not talked about enough.

On the rise

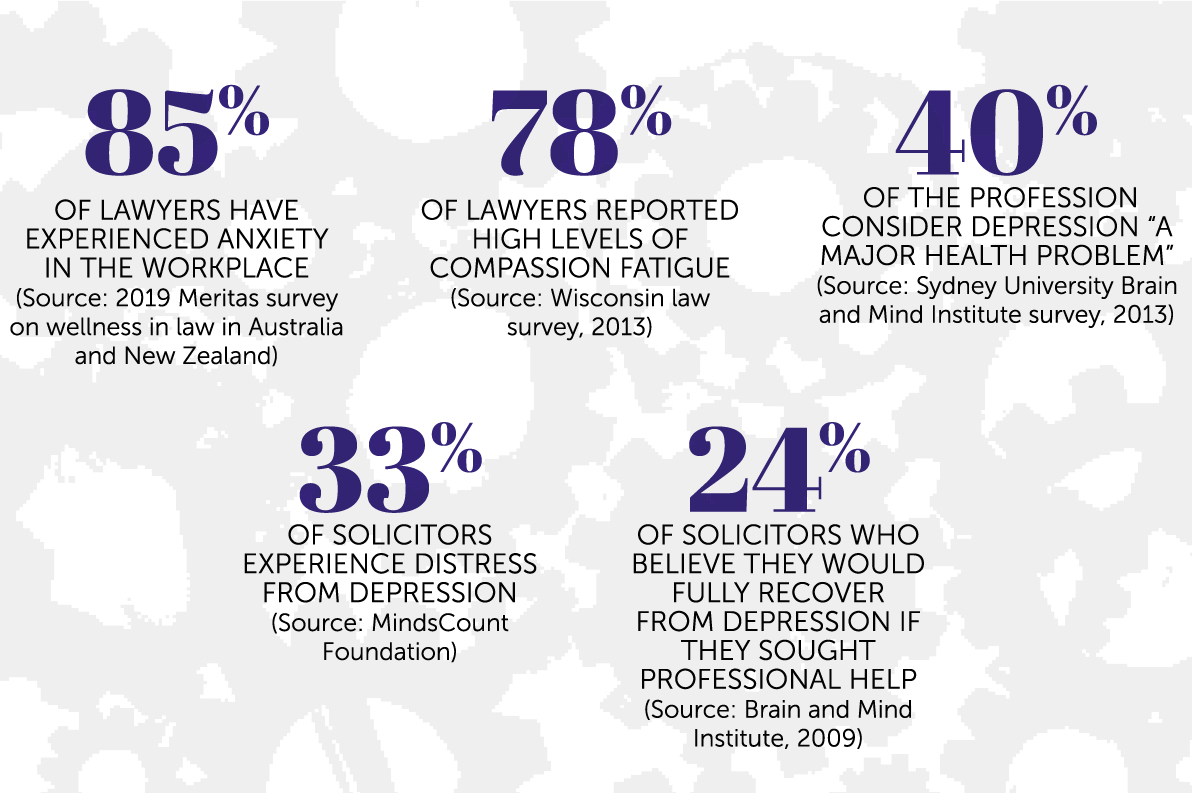

It’s still too early to measure the full impact of the pandemic on mental health, but early research suggests a significant increase in diagnoses of mental health conditions. One study published in the Medical Journal of Australia that examined Australians’ mental health in April – the first month of the pandemic – found mental health problems were at least twice as prevalent as before the pandemic began.

Since then, mental health services have reported a big jump in requests for support. “We have seen an absolute increase in demand for telehealth services, including mental health services,” says Dr Sadhbh Joyce, a senior psychologist at the Black Dog Institute.

“What that generally indicates is that the general population is feeling the stress and the mental health strain of the pandemic. When people are under significant stress it can put them at greater risk of common mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression.”

People with pre-existing mental health problems are at even higher risk of anxiety and distress during a disease outbreak.

“Law is a very stressful profession – it’s up there with frontline workers, first responders and people in the field of health who are at higher risk of mental health difficulties,” says Dr Joyce.

Indeed, Golding says it’s clear that professionals are looking for extra support. “In my private practice, I tend to work with people that are in the professional space and executive level, and the number of inquiries has increased dramatically,” she says.

President of the Law Society of NSW, Richard Harvey, said the Society is cognisant of the potential for increased impacts on the mental health of solicitors as a result of COVID-19 and associated challenges.

The flip side

Thankfully, it’s not all bad news. Like people from all walks of life, many lawyers have also enjoyed the change of pace and opportunity to evaluate what they really value in life.

“People have been able to reflect on their time in lockdown and question where it’s being spent,” says Dr Joyce. “That’s a very powerful question to ask as human beings as time is our only true currency – we never get more time. For those who put a huge amount of time and energy into their work, it’s really been something to consider.”

At firms that are slowly asking staff to return to the office, Setti says as many as 50 per cent of lawyers report being reluctant to leave their home office. “People are finding more time to do hobbies that they like and develop better relationships with family members and neighbours. What this pandemic has given some of us is the luxury of considering what was working for us and what wasn’t working for us in our pre-COVID-19 world.”

Managing mental health

With the ebb and flow of lockdowns and social distancing rules around the world, it’s evident that this pandemic will be more like a marathon than a sprint. So, what are some practical tips that can help to ease stress and anxiety, and reduce your risk of mental health problems?

Amidst so much uncertainty, having a regular workday routine is one of the most effective ways to create a sense of certainty – even if it needs to change over the months ahead. If the routine can help to delineate between work and home life, even better, says Dr Blashki.

“Routine is very important – work out the time you’re going to get up, start work and switch off from work,” he says. “You can also use symbols to help with the transition, like changing out of your work clothes at the end of the work day.”

Dr Joyce says it’s crucial that your routine includes self-care activities like eating a healthy diet, enjoying regular exercise, spending time with family and friends, and engaging in hobbies.

“For busy professionals there’s a tendency to resort to self-care when you can fit it in or when you’re feeling really burnt out and stressed,” she says. “That approach is never going to serve you long-term. We need to make self-care a foundation.”

Golding says a key aspect of self-care is positive self-talk. “The most important thing is to get comfortable with uncertainty and get comfortable being uncomfortable,” she says. “There is a lot of uncertainty but how you talk to yourself about that can make a huge difference.

“So rather than getting frustrated with it and talking to yourself negatively, practice taking a deep breath and learning to love and even thrive in what you might previously have thought of as chaos and unpredictability.”

Managing your media consumption is another helpful strategy. “Lawyers rate high on the scepticism scale, but it’s still important to be careful not to overdo your media intake,” says Golding. “We know that the media loves drama and fear because it sells, but getting caught up in it can be unhelpful for mental health.”

And if you’re feeling particularly flat for more than a couple of weeks, don’t be afraid to seek help from your GP or a mental health professional – in person or over the phone. The recently introduced Solicitor Outreach Service allows NSW solicitors access to three free counselling sessions a year.

The law society responds ...

Solicitors struggling with mental health can access up to three psychological sessions per financial year as part of the Law Society of NSW’s landmark mental health and wellbeing program, the Solicitor Outreach Service (SOS).

Law Society President Richard Harvey said the Law Society acknowledged the unique challenges of 2020 for the state’s 35,000 solicitors, including the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing recovery in the regions from bushfires and drought.

“The legal profession, like any other portion of society, is made up of human beings, so there’s always going to be a level of distress, but of course we have solicitors freely acknowledge that there is a great deal of pressure in legal practice,” Harvey said.

“As a result, the Law Society prioritised efforts to improving accessibility to qualified psychological services via our recently launched Solicitor Outreach Service.”

SOS connects NSW solicitors to confidential psychological support. By calling 1800 592 296 you can access: up to three psychological sessions per financial year, paid for by the Law Society of NSW and 24/7 telephone counselling with a psychologist if you are in crisis or distress. The SOS hotline will be operational around the clock, 365 days a year.

No information will be provided to the Law Society of NSW which could identify solicitors accessing SOS. For further details, visit lawsociety.com.au/sos

Inoka Ho is a family lawyer and legal consultant in Sydney. She shares her story.

“You can’t control what happens, but you can control how you react. In 2019, I worked on building up my mental resilience and sought out resources on this, through books and podcasts. If I didn’t have that grounding going into lockdown, I do not think I would have coped as well as I have over the period of isolation. Little things – like having a separate part of my dining table that is my work area and then leaving that once I finish for the day and never checking emails in bed – make a big difference. I like to start the day with a cup of coffee or tea and a book that enriches me, before checking my emails. It helps me set myself up for the day, rather than letting the day control me.

I think we have come a long way in the past 10 years. We definitely have a lot more people being open about things if they are struggling. But I think that the legal profession reflects the wider community, and the work of organisations like RUOK? – we have become part of a broader movement on this.

We say a problem shared is a problem halved. In the network I work with, I feel they are more open to saying, ‘You know, I am struggling this week’ and asking for help. I feel like as a profession, as colleagues, we need to be more open with eachother. I think there has been a fear in the past, especially in large firms, that there just isn’t a culture there that supports people speaking up about these issues. If you do, it’s just considered that you can’t cope with things and you are not up to the job, and people feel like they have to constantly keep up.

Certainly, from my experience as a law student, you don’t get taught the skills and equipment you need to deal with failures, setbacks and not being in control. And that is not talked about enough. Mental resilience is a big factor for me in how I have coped with the challenges of being a solo practitioner and the challenges of the pandemic.

We often talk about arming ourselves with tools to deal with these challenges, but that often involves what can be described as ‘lean out’ advice, like finding a hobby. That is really important, but I don’t think we do enough with helping people to ‘lean in’ to these challenges. I compare it to running a marathon. There are outward things you can do, and you can have cheerleaders encouraging you, but what gets you putting one foot over the other to the finish line is your inner mind.

I am still discovering new things that improve the way I see the world. It took the isolation of being in this situation as isolation that inspired me to change things. I have felt very fortunate to be able to connect with people using technology; it has made a huge difference during the restrictions. I can’t imagine what it would have been like during the Spanish Flu pandemic in 1918.

We have come a long way but there needs to be an ongoing commitment to a culture shift. Where we don’t just associate our success with the number of hours we have worked, our status in the office and achieving a promotion at work. It has to be holistic and healthy.”