In a special address at the Federal Court of Australia, Chief Justice Sir Gibuma Gibbs Salika of Papua New Guinea (PNG) commemorated the nation's upcoming 50th Anniversary of Independence and highlighted the critical role of legal pluralism in its judicial system.

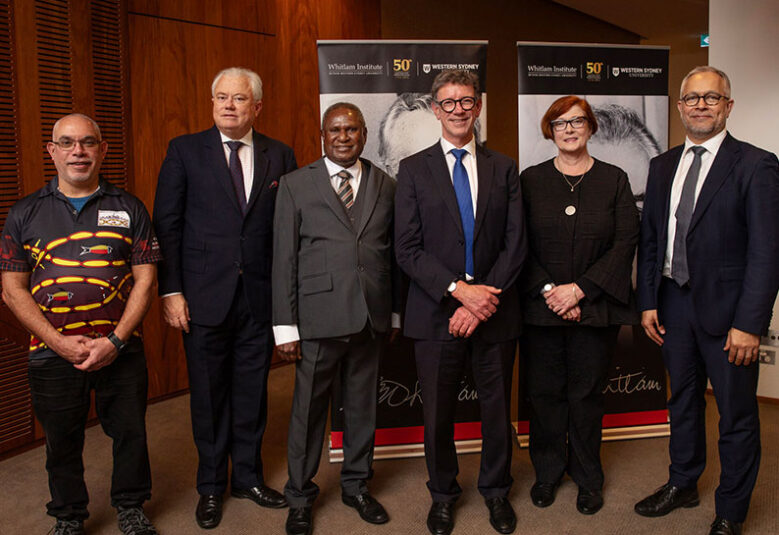

The event, hosted by the Whitlam Institute, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and the Federal Court, celebrated the legal and cultural ties between Australia and Papua New Guinea and highlighted the crucial role the judiciary has played in protecting democratic processes in PNG since independence, with attendees including distinguished members of the Australian judiciary and diplomatic corps.

Justice Stephen Burley of the Federal Court of Australia introduced Chief Justice Sir Gibbs Salika, calling him a “long-standing friend and partner of the Australian judiciary.” Burley noted Gibbs’ impressive career spanning over 35 years as PNG’s longest-serving judge in the National and Supreme Courts. He also highlighted the two nations’ enduring judicial partnership, which was formalised by a Memorandum of Understanding on Judicial Cooperation that has been in place since 2009. In his remarks, Burley stated, “democracy never sleeps, and the birth of a nation requires nourishment,” and that it was a “particular pleasure to be able to honour Sir Gibbs, whose court has done much to ensure that from its early roots, Papua New Guinea could grow and develop as a nation.”

PNG achieved independence on 16 September 1975, with then Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam playing a crucial role in the process. The Whitlam government accelerated PNG’s transition to self-governance, and at PNG’s independence ceremony, Whitlam famously acknowledged, “Australia could never be truly free until Papua New Guinea was truly free. In a very real sense, this is a day of liberation for Australia as much as for Papua New Guinea.”

However, this freedom came with the challenge of reconciling three legal systems: Customary Law, Common Law, and Statute Law.

“This is true legal pluralism putting academic theory to practice,”

A key theme of Salika’s address was legal pluralism, which he defined as the coexistence of traditional customary laws and the common law system in PNG’s administration of justice.

He stated that without the existence of legal pluralism in PNG, “the loss of our cultural identity, customs and dignity of who we are as individual cultural groups would have been lost.”

Chief Justice Salika emphasised that PNG’s “home-grown” Constitution is a unique document that provides a legal foundation for its system of legal pluralism. He stated that the decision by the nation’s founding leaders to incorporate “indigenous laws” into the constitutional context was a “significant milestone” in the birth of the nation, ensuring that the indigenous way of doing things was captured in addition to the common law.

“Such clarity of purpose provides assurance to the people of PNG that our indigenous legal development has a place within the modern PNG. This is true legal pluralism putting academic theory to practice,” Salika said.

The address underscored the deep ties between Australia and PNG, which share a common history and an enduring bond. It also served as a powerful symbol of the ongoing friendship and collaboration between the legal systems of both nations. Former Senator for NSW and current Whitlam Institute board member Marise Payne said that the connections between the courts in PNG and Australia are “strongly emblematic of that close relationship,” but added, “[N]othing exemplifies better or is stronger than our people-to-people relationships,” connections formed through history, war, communities, education, and the judiciary.

Australia, like PNG, grapples with the concept of legal pluralism, though in a distinct way. While Australia’s legal system is primarily based on Common Law and Statutory Law, there’s a growing recognition of Indigenous customary law. The High Court of Australia’s landmark Mabo decision in 1992 was a pivotal moment. It overturned the doctrine of terra nullius (“land belonging to no one”) and recognised that a form of native title to land existed at the time of British settlement. This decision acknowledged that Indigenous customary laws and traditions have a legitimate place in Australia’s legal framework, especially concerning land rights.

However, the coexistence of these legal systems remains a complex issue. While native title is now part of Australian law, Indigenous customary law is not fully integrated into the mainstream legal system. Unlike PNG’s Constitution, which explicitly recognises customary law as a foundation of its legal system, Australia’s approach has been more gradual and case-by-case.

An article published on LSJ Online last year argues that Australia’s common law system, which is based on a Western concept of family and inheritance, is ill-suited for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and that recent amendments to intestacy laws in New South Wales are a step toward recognising and accommodating Indigenous customary law.

The challenge for Australia lies in reconciling these systems to achieve a more equitable application of law for its First Nations peoples, which is part of a broader national conversation about constitutional recognition.

Photo Credit: Sally Tsoutas, Whitlam Institute