While often used interchangeably, the concepts of morals and ethics have subtle but important distinctions. Understanding these differences will guide how we navigate complex situations and address issues like recovering from moral injury.

Morals: Can be seen as your personal compass, guiding your individual decisions based on internalised principles like honesty, fairness, and equality. Morality often carries a religious connotation, with moral theology being a cornerstone of many faith traditions.

Ethics: Ethics, on the other hand, serve as a community-driven code of conduct. Think of it as a framework established by groups like businesses, professions (medicine, law), or even society at large. These codes define acceptable behaviour within specific contexts.

While morals provide a personalised sense of right and wrong, ethics set broader standards based on societal values and legal boundaries. Many moral dilemmas arise when individual morals clash with established ethical codes.

Healing from Moral Injury

Recovering from moral injury, when personal beliefs are deeply challenged by experiences, requires a customized approach based on individual values and beliefs. Various pathways like talk therapy, religious dialogue, creative expression, and group discussions can facilitate the healing process.

Healing doesn’t happen in a vacuum. The social context, including family, community, and organisational culture, plays a crucial role in supporting the individual’s journey. Additionally, core personal values and the influence of changing societal attitudes over time further shape the recovery process.

Where do you assign responsibility?

Locus of control theory

The Locus of Control theory, developed by Julian Rotter in the 1950s, explores how individuals perceive the control they have over events in their lives. It categorises people into two main groups:

Internal Locus of Control Group

- Take responsibility for their own actions

- Less influenced by the opinion of others

- Work hard to achieve the things they want

- Feel confident in the face of challenges

- Report being happier and more independent

External Locus of Control Group

- Blame outside forces for their circumstances

- Credit luck or change for any success

- Don’t believe they can change their situation through their efforts

- Feel hopeless or powerless in the face of difficult situations

- More prone to experiencing learned helplessness

Circle of Concern model

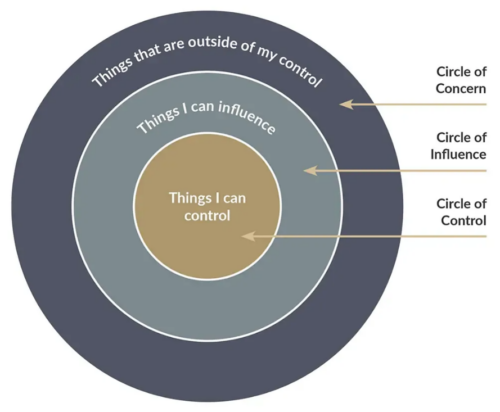

The Circle of Concern model, popularized by Stephen Covey in his book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, helps individuals focus their energy on areas where they can truly make a difference. It consists of three overlapping circles:

Circle of Concern: This represents everything we care about or think about, regardless of whether we can control it. It includes global events, other people’s behaviors, the economy, the weather, and basically anything that impacts us in some way. Worrying about things in this circle is natural, but dwelling on them can be draining and unproductive.

Circle of Influence: This is the smaller circle within the Circle of Concern, encompassing the areas where we can exert some influence. This might include our own actions, reactions, choices, attitudes, and communication. By focusing on this circle, we can channel our energy into making positive changes in our own lives and those around us.

Circle of Control: This is the smallest circle, representing the things we have direct control over. This typically includes our thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and choices in specific situations. Focusing on this circle helps us prioritise our efforts and take responsibility for our own well-being and actions.

The key takeaway of the model is to shift our focus from the overwhelming Circle of Concern to the more manageable Circle of Influence and, ultimately, the Circle of Control. By consciously directing our energy towards areas where we can make a difference, we can reduce stress, increase effectiveness, and live more fulfilling lives.

Therapeutic modalities that can help

While PTSD and moral injury are linked, the latter isn’t classified as a mental illness. This distinction is crucial when seeking treatment. Fortunately, several therapeutic modalities can support healing after a moral injury. These include:

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy adapted for moral injury: This therapy focuses on aligning actions with personal values through self-compassion and mindfulness practices,even when guilt lingers.

- Individual therapy: Exploring personal values,both upheld and violated during the traumatic event, aids in evaluating beliefs and assigning responsibility in hindsight.

Moral Reckoning with Self Compassion

Facing a moral transgression often triggers a storm of emotions: shame, guilt, anger, injustice, and fear. These emotions fuel anxieties and can lead to social withdrawal. However, the Circle of Concern model can assist by helping us understand how much control we truly have over events and reframing these rigid thinking styles. Accepting the things we cannot change while taking responsibility for our actions allows for self-forgiveness and the courage to express bottled emotions, allowing us to take the first step towards healing and reconnecting with society.