“Imagine if we were free and the system actually invested in our youth. We have so much to offer, but we can’t do that in jail.”

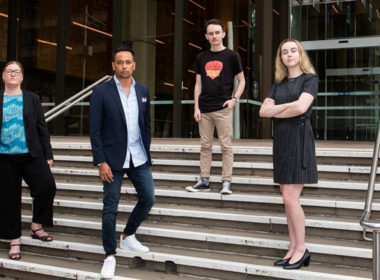

The legal profession is more diverse than it has ever been. Our newest lawyers are chasing goals so big they could change the way we practise forever.

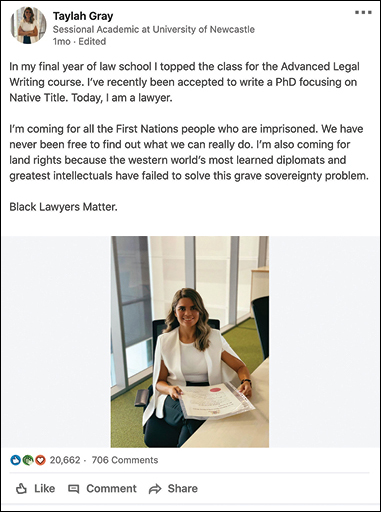

Even if you don’t know Taylah Gray’s name, there’s a fair chance you will recognise her face. The new lawyer, who was admitted in March this year, posted a photo to her LinkedIn profile with her crisp certificate of admission that attracted more than 20,000 likes.

When asked why the post garnered so much attention, she doesn’t hesitate: “Black lawyers matter,” she responds.

Gray, originally from Dubbo, is a proud Wiradjuri woman. She’s a sessional academic at the University of Newcastle who is about to dive into a PhD focusing on native title, sovereignty, and economic theory. She’s a fierce advocate for Australia’s First Nations communities and she proudly led the Black Lives Matter rallies in Newcastle last year, even getting a prohibition order struck out in court so her community could protest for justice. Next, she’s got her sights set on a treaty.

Pursuit of justice

There are two key issues in Gray’s sights. The first is the question of native title, and finding a solution that will allow everyone to come together and benefit from the land without “mining the hell out of it”. Native title stems from case law, but Gray argues legislation has watered down the rights of First Nations people, largely due to the misconception that it could be applied over private land – and white people own a lot more land than people from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds.

Taylah Gray

Taylah Gray

The second is the rate of incarceration among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. First Nations people make up approximately 3 per cent of Australia’s population, but represent about a quarter of all adults and about half of all young people in criminal detention. In 2019, the Northern Territory’s Social Policy Scrutiny Committee was told that every single child in detention was Indigenous. “It’s sickening,” Gray says. “Imagine if we were free and the system actually invested in our youth. Once we’re free we can really give back to society. We have so much to offer, but we can’t do that in jail.”

Once her thesis is done, she plans to become a criminal defence lawyer, but she knows the road ahead won’t be easy. “I feel misunderstood. There aren’t many First Nations lawyers in there,” she says of the profession. “What’s going to happen in the future? I don’t know. What I really want is a treaty and I’ve got tunnel vision for that. Sometimes it makes me angry, and the power of an angry black person is often misconceived. When you’re sad, you cry. When you’re angry, you do something about it.

“There’s a lot of unfinished business on this land.”

Changing our constitution

There are currently 36,400 solicitors with practising certificates in NSW, according to Law Society records from December 2020. About 19,000 are female and about 17,000 are male. The greatest number are in the 30-39 age bracket, with an estimated 30 per cent of practitioners falling into this category.

The data shows that 42 per cent work as employees of law practices. Almost half – 48 per cent – work in the city while 34 per cent work in suburban law firms. Limited data exists about ethnic diversity, save for the 2018 National Profile of Solicitors report, which revealed the number of First Nations solicitors decreased in proportion after 2014 to less than 1 per cent of solicitors around the country.

Anecdotally, there has been a significant increase in the number of lawyers joining the profession from racially, culturally, and socially diverse backgrounds. The fresh faces flooding in on LinkedIn, posing in front of the Supreme Court of NSW with their parents, partners, or the lawyers who moved their admissions, certainly indicate that to be the case. It doesn’t yet match the community it represents, but the profession has come a long way, and diversity is a priority all the way to the upper echelons.

Priorities from the bench

“When we think of the diversity of the legal profession, we encounter the duality that we have come very far, and that much still needs to be done,” the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of New South Wales Tom Bathurst said at an admission ceremony for new lawyers in December 2020. Representation of women, he noted, has transformed since the days when they were not allowed to practise at all.

However, the Chief Justice flagged other noticeable concerns “that we must face head-on”. He pointed to a lack of representation of First Nations people, of those from diverse cultural backgrounds, and those from less privileged backgrounds, in his address. But there is hope that the profession will eventually reflect the community.

“There is far greater diversity of background among junior lawyers than those who have been around as long as me – and you only need to look around the courtroom, and then at the paintings on the walls, to see so,” he told the new cohort. “You are in a unique position as new lawyers who are entering the profession at a time when, more than ever, your words and actions are having an impact for good … You are the future of the profession and will steer the direction it will take.”

Faces of change

Ferdous Bahar, who was admitted in November last year, is one of them. She’s currently in the final rotation of her graduate role at Ashurst, working with the Intellectual Property and Media team, and she proudly volunteers as a member of All at Ashurst, the company’s multiculturalism network.

“I’ve wanted to be a lawyer since I was in year four,” she tells LSJ. “My parents were supportive, but we didn’t know anyone who had studied or practised law in Australia. It was a steep learning curve on many levels.”

Bahar is Bengali Australian and a practising Muslim. Born in Bangladesh, her family moved to Minto, in the south-western suburbs of Sydney, when she was one. She has always been a passionate debater and a skilled writer, and says her biggest motivator has always been access to justice. She first jumped into advocacy as the Ethnocultural Officer at the University of Sydney Law School, which was a big factor in her decision to choose Ashurst. In addition to the excellent legal training, she explains, she immediately felt like people were listening when she talked about the importance of diversity in the legal profession.

Ferdous Bahar

Ferdous Bahar

“My parents were supportive, but we didn’t know anyone who had studied or practised law in Australia. It’s not the usual pathway into the profession.”

“Speaking as someone who is very active in conversation about racism and systemic discrimination, I think a lot of people are unaware of how deeply entrenched these things are in Australia,” she says. “Part of my role is encouraging people to feel they have a safe space to talk about these issues, and part of it is actually helping to create that safe space through our initiatives.”

Her work with the multiculturalism network has given her the ability to have important conversations with lawyers at all levels of the firm. And while the profession has a long way to go, she’s optimistic about the future.

Then versus now

A lot has changed since Keerthi Ravi was admitted to practice six years ago. She was the only person of colour in her original clerkship cohort, but she says she really noticed the disparity in her first few years of working full-time.

“There was not even a discussion about cultural diversity or race when I started,” she says. “People put their heads down and worked hard and that was it. Now I get people knocking on my door asking to talk. People are aware this is an issue and they want to do something about it.”

Ravi, who was born in India and migrated to Australia at the age of 10, moved to Sydney and joined Allens in 2018. She currently works in the regulatory investigations and commercial disputes team as a senior associate and is the co-founder of a not-for-profit group called Diverse Women in Law (DWL) to support female lawyers in all stages of their careers.

Keerthi Ravi

Keerthi Ravi

“People might look different, but they also often present differently, and that comes with different strengths that can be harnessed.”

“Diverse numbers are increasing, but it’s often hard for people to find mentors and build the confidence to find their voice and use it.

“People might look different, but they also often present differently, and that comes with different strengths that can be harnessed.”

DWL launched a membership program in December 2020, which has already grown to include 400 law students and 120 mentors. More than 800 people receive the mailing list and 10 corporate sponsors have come on board: Ashurst, Herbert Smith Freehills, Norton Rose Fulbright, Minter Ellison, Baker McKenzie, Thomson Geer, Wootton and Kearney, Gilbert and Tobin, Allens, and Carroll O’Dea.

“I started putting the word out and people came in droves. It was incredible,” Ravi says. “I spent years talking to people to understand what the issues were and what we were trying to resolve. I found a gap around intersectionality when it comes to women.”

DWL’s key focuses moving forward are leadership and retention, to ensure the ranks of female lawyers are ready for promotion in years to come.

Advocating for change

Representation is also important for clients. This is something Nicholas Stewart, a criminal lawyer, sees on a daily basis. He found the law after completing a commerce degree and landing a job that required a lot of statutory interpretation, which he loved from the outset.

“I knew this was for me,” he says. “But did I see anyone like me? No, I didn’t. Even in law school, I didn’t really see many members of the LGBT community, at least not visibly.

“I was living my gay life outside of my student life.”

Stewart obtained a clerkship at Minter Ellison, which he says was “phenomenal”. He found out the firm was advising the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, so he joined a group of lawyers who were on the committee and connected with other employees who were members of the LGBTQI+ community. As his career progressed, he joined Dowson Turco – “Australia’s only out and proud law firm” – as a partner.

“It allowed me to really share my personal life and my professional life,” he says. “It was confronting in a way, because it made me realise how important the law is to the LGBT community and that there are parts of the law that need better experience when these clients are navigating legal issues.”

It has allowed him to dive headfirst into social issues – such as pushing for the recent parliamentary inquiry into gay hate crimes and supporting four gay police officers who sued NSW Police for discrimination.

“We’ve done so much at the firm in terms of acting for clients in really difficult situations where there is a connection between their legal circumstances and their sexuality. We pride ourselves on being technically brilliant lawyers, but our sexuality gives us an edge. We’re lawyers before we’re gay.”

Shaping the profession

The future is bright and there is perhaps no better example than Raul Vellani. He was admitted last December and is currently working as a graduate at Herbert Smith Freehills. Vellani is still deciding what his next step will be, but his enthusiasm for the law and legal practice is contagious.

“I think I’ve always known that I was going to be a lawyer,” he says. “The degree was fun, but it also felt like a mandatory waiting period until I could start working. I learnt a huge amount, obviously, but this is what I’ve been most excited about. I’m so lucky that I wake up every day and know I’m in the right profession.”

Raul Vellani

Raul Vellani

“Clients increasingly want diversity of thought going into their matters. We have to recognise that diversity has benefits all by itself.”

Vellani was born in Australia to Singaporean and Indian parents, and grew up at Beecroft, on Sydney’s upper north shore.

“I’ve always grown up around a huge selection of different people and from day dot I’ve learnt to value that. It’s normal to me.”

Upon reflection, he says there are three reasons why diversity matters in law. First, he says, it’s essential in terms of equitable access for new lawyers. Second, in his experience, diversity of thought really does lead to more well-considered outcomes. Finally, he believes it’s good for business.

“Clients increasingly want diversity of thought going into their matters,” he explains. “We have to recognise that diversity has benefits all by itself.”