It is said that those who come to equity must come with clean hands. But what of those who come to the law with empty pockets? Statistically speaking, most lawyers in Australia come with pockets lined by wealthy families and relatively privileged backgrounds. In comparison, prospective lawyers from low socio-economic circumstances battle systemic biases and disadvantage. Until this changes, the legal profession cannot hope to achieve true diversity.

Few white-collar professionals know what it is like to have lived below the poverty line. Lawyer Arlia Fleming does. At various points in her youth, Fleming was homeless and cashless, with no secure bed to sleep in, no income and no family support to fall back on. Her low socio-economic background meant her pathway to becoming a lawyer was never typical or straightforward.

“It was really just life circumstances that made things difficult,” she tells LSJ. “I came from a single-parent household and was the first in my family to go to university. There was no easy road into law school and to get admitted to legal practice.”

Fleming grew up attending public schools in the Hawkesbury and western Sydney regions where her mum, who worked in hospitality, could find affordable rent. She started washing dishes in restaurants at age 14 to contribute to household bills. No one in Fleming’s family had a tertiary degree and for a long time it seemed out of reach for her, too.

Studying law while working to keep a roof over her head – as an 18-year-old living out of home with no financial assistance from parents – was an arduous balance. Fleming dropped out of her first year studying a Bachelor of Criminology at University of Western Sydney. She tried TAFE, dropped out, then finally went back to university to study law at Southern Cross University in Lismore at 19, where the lower cost of living put graduating within reach.

“I was on Centrelink and I always struggled to pay rent, always lived in share housing, which comes with its own challenges,” she tells LSJ.

“I would spend hours every semester trying to track down second-hand textbooks, often relying on the outdated version of a textbook so I wouldn’t have to buy the new one. I remember being in classes, scrambling to find and match up the pages of the textbook in the reading material to the old edition I had.

“In my first year studying law, it was so overwhelming. I was trying to live out of home, everything was so difficult, and it was really challenging for me. A series of events in my life led to me being homeless for a time.”

How many lawyers come from poor backgrounds?

More than 15 years on, Fleming now manages and is Principal Lawyer at Elizabeth Evatt Community Legal Centre in the Blue Mountains. She took 10 years to pay off her student debt but finally managed it in 2018. Becoming a lawyer, she says, has provided life-changing financial security she never experienced growing up.

Fleming’s story is not completely rare, but it is certainly not common in a legal profession historically dominated by wealthy white men.

As Angela Melville, a senior law lecturer and published researcher at Flinders University, wrote in her 2014 report Barriers to Entry into Law School: An Examination of Socio-economic and Indigenous Disadvantage, “Until the early 1970s, the Australian legal profession was almost exclusively the domain of white men from privileged backgrounds.”

Since then, the profession has made considered efforts to promote – and, in many cases, achieve – greater diversity based on measures like gender, race, and LGBTQI status. In 2018, the Australian profession even reached an historic milestone in gender diversity, reporting more women than men solicitors across the country. But, as Melville notes, the number of lawyers from low socio-economic backgrounds has remained persistently low.

While there is no published data about the socio-economic backgrounds of practising lawyers across Australia (the NSW Law Society’s National Profile of Solicitors does not collect it), university student enrolment data offers some insights into the relative wealth of students gaining entry to law courses. This is relevant because these students make up the pool of graduates from which the legal profession can be formed.

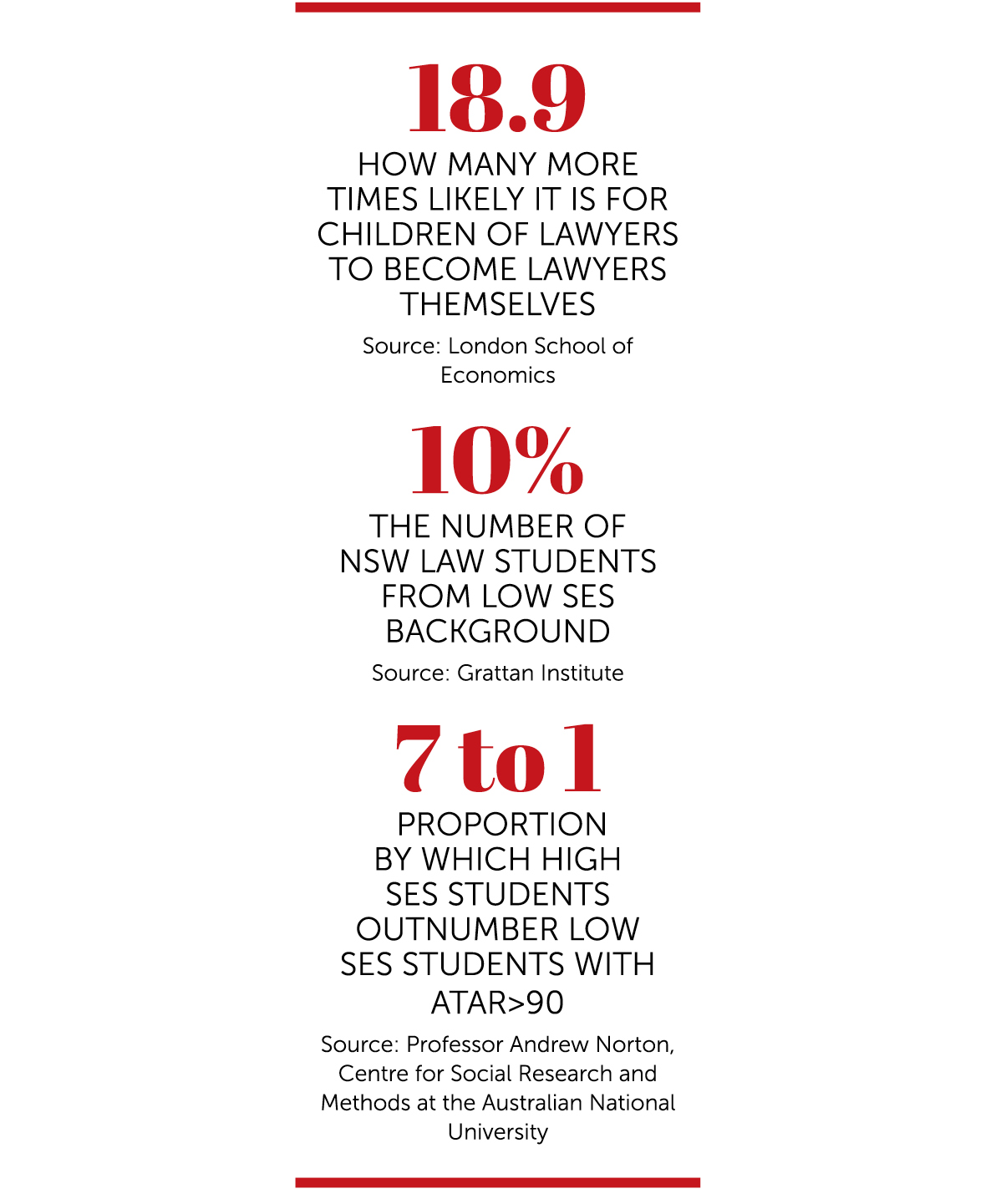

According to research by the Grattan Institute, just 10 per cent of high school students enrolling in law degrees across Australia between 2005-2015 came from the lowest quartile of socio-economic status measures as defined by the Department of Education. Almost 60 per cent of law students came from the top two quartiles.

Andrew Norton, a professor in higher education policy at the Australian National University, explains this is largely because the high ATAR entry requirement for law degrees disadvantages students from low socio-economic backgrounds.

“Law is at the lower end of the range for low SES [socio-economic status] enrolment share,” he tells LSJ. “This is primarily due to the relatively high ATARs required for most law courses. Higher SES school leavers dominate the top range of Year 12 performance.

“In NSW, high SES students outnumber low SES students in the 90-plus ATAR group by more than seven to one.”

At the University of Sydney, home to one of Australia’s most prestigious law schools, the ATAR requirement for guaranteed entry to law in 2020 was 99.50. The University of Wollongong offered a slightly more attainable mark of 92.

UNSW Law requires students to undertake the two-hour Law Admission Test (LAT), which assesses students on a range of skills and aptitudes for law, such as problem-solving, comprehension and analysis. The LAT is considered complementary to the ATAR and can assist students from high schools with lower weighted ATAR marks. In 2020, the lowest ATAR for admission to UNSW Law was 88.15.

However, even that ATAR could be difficult for students with backgrounds like Fleming, who may be juggling high school with part-time work and the myriad other stresses that come with poor socio-economic status.

“It’s pretty well known that the ATAR ranking system comes down to your cohort and your school,” says Jason O’Neil, an Indigenous lawyer from Parkes in central NSW, who earned a place at UNSW Law eight years ago via an Indigenous scholarship scheme.

“I was at a pretty big disadvantage compared to other students applying to law from elite Sydney high schools,” says O’Neil. “I came first or second in most of my classes at high school but that didn’t give me the mark I needed, with the ATAR ranking system the way it is. When I arrived at UNSW in my first year, everyone was talking about what Sydney high school they attended – I had never heard of these schools. I was stunned.”

O’Neil received an ATAR in the 70s – almost 30 points off the required mark for guaranteed entry to UNSW Law. However, after gaining alternative entry through UNSW’s Indigenous Pre-Law program, O’Neil graduated with Honours in 2018 and was awarded the university medal for his success. He was admitted as a lawyer in NSW in 2019 and is now the director of Ngalaya Indigenous Corporation, the representative body for First Nations lawyers and law students in NSW.

“My parents did not go to university. They owned a video store and worked as couriers,” he explains.

“Dad was a truck driver. Mum is Indigenous. But when I started studying law, the instant generational impact on my family was so obvious. My little brother started talking about going to university. He applied for the Indigenous entry scheme and is now at UNSW with me [Jason is studying a PhD].”

Embedding disadvantage

Diversity has become the catchcry of law firms across the nation in recent years. The legal profession has held events, conducted surveys, published studies, and shouted warnings about unconscious bias and the business failures that can stem from a lack of diversity. But it seems little or no spotlight has been shone on socio-economic or class-based discrimination; an issue that has ripple effects impacting all other types of diversity in law.

Even as firms begin to set racial diversity or gender targets – as many Australian mid- and top-tier firms have done recently – socio-economic biases will persist as long as the profession favours those who can afford to dress sharp and “present” well. A study by a coalition of British and Scottish universities, submitted to the UK Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission in 2015, found that elite firms defined “talent” in recruitment based on factors such as drive, resilience, strong communication skills, confidence and “polish”. The authors pointed out these are traits of middle-class status and socialisation.

In the UK, where the “class” of a person’s socio-economic status still largely depends on family wealth, researchers have also documented the disadvantage working-class people face when trying to break into high-status professions like law. Utilising a large data set from the UK Labour Force Survey, the London School of Economics found the legal profession has a distinct pattern of “micro-class reproduction”: children with parents who were lawyers were 18.9 times more likely to become lawyers than the population as a whole.

There is no similar mapping of the professions in Australia, but Fleming believes we suffer similar problems. Some commentators point to the recent promotion to the High Court of Justice Jacqueline Gleeson, the daughter of former High Court Justice Murray Gleeson, as symptomatic of micro-class reproduction in the legal profession.

“It’s still a very insular profession,” says Fleming. “I have been lucky enough to go and move the admission for graduates who come through our legal centre. You still see there are at least half a dozen people who get up and they are moving the admission for their daughter, or their nephew or their wife.”

It’s pretty well known that the ATAR ranking system comes down to your cohort and your school. I was at a pretty big disadvantage compared to other students applying to law from elite Sydney high schools, I came first or second in most of my classes at high school but that didn’t give me the mark I needed, with the ATAR ranking system the way it is.

Zaahir Edries, a Muslim lawyer from a South African migrant family, who is General Counsel at GetUp and former President of the Muslim Legal Network NSW, agrees.

“Let’s just say this: it’s more often that John moves his son Mark’s admission, than Hassan moves his daughter Amira’s admission,” says Edries.

Edries explains that having a lawyer in the family offers dual advantages to aspiring lawyers: parents are more likely to be able to offer housing or financial assistance to their children studying at university. This gives the children more time to focus on study and achieving high marks, putting them ahead of other graduates who split their time between studying, working, and all the time-consuming domestic chores that come with living away from home. On top of this, family links in the profession can assist graduates looking for work in a tight legal market upon graduation.

“If you don’t have to work at university, there is no question you will have more time to study and get good marks,” says Edries.

“I was from a migrant family; my father was a cab driver and I moved out of home to go to university. I worked three jobs; at Big W and Kmart and as a paralegal just to afford the rent in Sydney. There’s no way that I was going to get high distinctions. I didn’t do well because I couldn’t afford to do well.”

Law affects the lives of every single person in the community and yet the experience of law across our community can be very different. A profession that reflects the diversity of our community is one that better understands the needs of the clients it represents.

Higher fees, higher barriers

As long as the pool of Australian law graduates remains shallow in terms of socio-economic diversity, the diversity of the legal profession can only reach as deep as that shallow pool. Unfortunately, barriers at university still prevent many students from poorer backgrounds trickling in.

This inherent disadvantage became amplified in August, when the federal government announced sweeping changes to university fees. Under a reform package sometimes dubbed “the Tehan reforms” (for Education Minister Dan Tehan), which passed parliament in October, the government decided to drop its financial contribution to law courses by up to 28 per cent. It also proposed to remove government fee assistance (those long-lasting HECS-HELP loans) for students who fail more than half their first-year subjects.

Tasmanian Senator Jacqui Lambie wrote on Twitter that “this bill makes university life harder for poor kids and poor parents … The ones who get pushed out of their preferred courses based on price are the ones who are watching ever dollar, knowing they might need that money down the track”.

She said the idea to remove funding assistance for students who fail half their subjects in first year would disproportionately affect Indigenous students and favour “rich kids” who could afford to study full time.

Toni Mudditt, a final-year Honours student at the University of Wollongong (UOW) and President of the UOW Law Student Society, agrees.

“People fail for a myriad of reasons – none of which would make them a bad lawyer,” she tells LSJ. “I think it’s quite upsetting. The legal profession already has a diversity problem. The government may not have considered the impacts it will have on people who are coming from diverse backgrounds and are not privileged.”

Neither of Mudditt’s parents went to university. A plumber and a bookkeeper living in the south-coast regional centre of Nowra, they could not afford to help Mudditt move out of home and rent closer to campus. It meant Mudditt was always juggling a 2.5-hour round trip to attend university with working at a Nowra pharmacy and a law firm in Ulladulla, on top of getting her nose in law textbooks whenever she could squeeze in time.

Mudditt will leave university at the end of 2020 with a HECS-HELP debt equivalent to the cost of a house deposit in areas around Ulladulla. She tells LSJ she would be reconsidering her decision to study law if she was applying under the new fee system.

“Law degrees are already incredibly expensive,” she says. “My degree costs about $50,000 and then it will be another $10,000 for the College of Law. I will finish this year with about $60,000 in debt.

“If I was applying for university this year, with the fee increases, I’d definitely be reconsidering my options.”

A profession for the one per cent

The Special Committee of Law Student Societies of NSW Young Lawyers, of which Mudditt is a member, wrote to LSJ in the wake of the university fee hikes, expressing alarm about the financial burden people from less privileged backgrounds will carry into the future. The deterrent effect of this burden means law risks becoming a profession for the wealthy that does not represent the broader community.

“Increasing the financial burden future law students need to carry upon completing their degree is not conducive to an accessible and diverse legal profession,” the committee wrote in a statement to LSJ in October.

Dean of UNSW Law Andrew Lynch believes any lack of socio-economic diversity has ongoing impacts for the rule of law and the development of our legal system more broadly.

“Law affects the lives of every single person in the community and yet the experience of law across our community can be very different,” he says. “A profession that reflects the diversity of our community is one that better understands the needs of the clients it represents. Lastly, a diverse judiciary, drawn from such a profession, is best able to serve the whole community, rather than narrow sectional interests.”

Fleming, meanwhile, reflects that people from lower socio-economic status backgrounds might be better equipped to help some clients. Her broad life experience has been invaluable in informing her work in the community legal sector.

“My experience is that I have a great deal of empathy for people,” she tells LSJ. “I don’t judge people for their experiences or where they ended up. I’ve worked with people in prisons, in various disadvantaged communities in rural and remote areas.

“Do people from high socio-economic status backgrounds have the same rapport with clients? I don’t think so.”