Equity is well and good, in theory. But how far is the legal profession from really achieving equitable outcomes for First Nations Australians? We ask three Indigenous lawyers to give it to us straight.

“Australia, as we know, hasn’t always been an inclusive society,” UNSW Professor of Law Megan Davis said in a powerful speech during the NRL’s 2021 Indigenous round. “There was a time when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people lived under extremely oppressive and draconian restrictions, known as the ‘protection era’ in Australia – a rather benign term.”

It was a time of compulsory racial segregation, she continued, when freedoms were restricted and brutal policies were actively trying to destroy the world’s oldest living culture. Fast-forward to today, and reconciliation is the word of the month – but what does that mean in a practical sense?

LSJ invited three prominent Indigenous lawyers to discuss how far the legal profession has come, and how far we have to go.

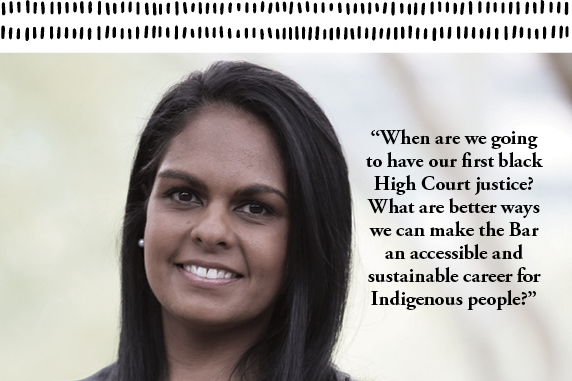

Teela Reid

Teela Reid is a Wiradjuri and Wailwan woman, a Sydney-based solicitor, advocate, and writer who gained notoriety for a fiery exchange with former Prime Minister Malcom Turnbull about the Uluru Statement from the Heart on ABC news panel program Q&A in 2017. Reid is a leading advocate for the proposal to officially establish an Aboriginal sentencing court in the NSW District Court, known as the Walama Court.

What does the Uluru Statement from the Heart mean to you?

The Uluru Statement is the most significant legal and political document of our time. I was a working group leader on s 51(xxvi), the Race Power, in the Sydney constitutional dialogue process and this was a profound experience for me as a young lawyer, because I was mentored by elders. In particular, Uncle Sol Bellear, who is no longer with us. Along the way we have lost elders in this struggle and it is so important that the next generation step up to continue the fight for voice, treaty and truth.

The Statement covers a lot of different issues, including structural problems in criminal justice and constitutional reforms. In your view, what are the most significant things the legal profession can do to support Indigenous Australians and ensure they are heard?

It’s important that the legal profession continue to support the Statement by sharing correct information. That way, citizens can make informed decisions about their understanding of our history, and Australia’s unfinished business with Indigenous peoples, and why it’s essential we all support this movement. As lawyers, we play a critical role in powering the peoples’ movement.

We have a privileged position in society to understand legal and political structures and how these institutions historically silenced and oppressed Indigenous people. It’s time to put power back into the hands of Indigenous people through critical changes to strengthen our democracy. The Uluru Statement invited the Australian people to enshrine a First Nation’s Voice in the Constitution and to establish a Makarrata Commission to enable national processes of treaty making and truth telling.

You’ve written an essay called “The Art of Seeding First Nations Sovereignty – Can You Handle the Truth About Treaty?” What is the truth? What should people know about Treaty?

This was one of my favourite essays to write. It’s essentially analysing what sovereignty is and how we enforce it, bearing in mind lessons from other jurisdictions such as treaty processes that have diminished [the rights of other Indigenous peoples]. It distinguishes the notion of sovereignty from an Indigenous perspective by highlighting other factors, such as power and accountability, which is what the Uluru Statement from the Heart attempts to correct.

Ultimately, the essay is about how Indigenous sovereignty cannot be ceded by western laws, and the importance of storytelling in Indigenous communities that are written into the landscape.

How can we make the law more equitable for Indigenous people?

We need to ask ourselves what an Australian Republic looks like – how we redefine our nation to break the shackles of our colonial past. We need to remain vigilant about how the law has been weaponised to oppress Indigenous peoples and go on our own journeys of understanding the truth about our nation’s history. I also think we should remain vigilant and call out racism in our profession. If we want to grow our profession and ensure Indigenous people feel safe in it, some things need to change.

When are we going to have our first black High Court justice? What are better ways we can make the Bar an accessible and sustainable career for Indigenous people? We also need to constantly ask ourselves whether we’re enabling racist systems, or working to dismantle these systems. What legacy is our profession going to leave the next generation?

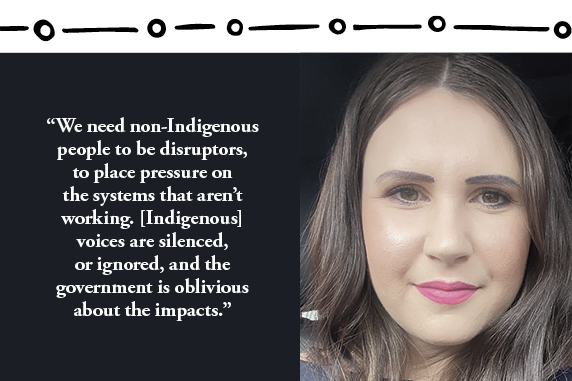

Danielle Captain-Webb

Danielle Captain-Webb is a Wiradjuri and Gomeroi woman. She is a criminal lawyer at Legal Aid NSW and Chairperson of the Darkinjung Local Aboriginal Land Council. Captain-Webb entered law through an alternative pathway at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) and began her career with the Australian Federal Police. Captain-Webb is based at Gosford, on the Central Coast.

What could the legal profession be doing better as allies?

We talk a lot about non-Indigenous people being allies of Indigenous people, but I think it needs to go further than that. We need non-Indigenous people to be disruptors, to place pressure on the systems that aren’t working. A lot of the time, [Indigenous] voices are silenced, or ignored, and the government is oblivious about the impacts things like procedures and processes have on us. I think sometimes lawyers forget our broader role in society – for me, for example, I’m a criminal lawyer. That’s my job, day in and day out. Lawyers get pigeon-holed, but we’re all admitted as officers of the Supreme Court and society looks at us as being change-makers. We need to think broadly about what we can do better.

Indigenous Australians are incarcerated at much higher rates than non-Indigenous Australians. As a criminal lawyer, what’s your view as to the best way to improve outcomes?

For me, a big part of it is truth-telling. Australia is slowly starting to move towards acknowledging the truth and talking about what our people have gone through. Why are we the fastest-growing population in custody? Why are our children still being removed in such significant numbers? Truth-telling allows healing. We still carry trauma with us every day, from our grandparents and great grandparents in the Stolen Generation. Our language was taken from us. Our cultural practices were taken from us.

Younger generations don’t know the stories and the traditional practices, and when they do, they don’t know what it means. Within Aboriginal communities, people have complex mental health conditions, health issues, addictions. The criminal justice system isn’t equipped to deal with those things. We have community corrections, probations, and parole. The system needs to adapt from a punitive approach to more of a healing framework. How can we do better? We need to start with young people. We’re going through what some people are calling a second stolen generation. There’s a lot of overlap between children in out-of-home care and those who enter juvenile justice. That’s where we should focus.

There’s been a lot of research done in this area and, in some respects, the intersection of the social and justice systems looks like a revolving door. Would extra support make a real difference?

Myself and my husband – he’s also a lawyer – finished Year 12 and didn’t know what to do. We couldn’t get into law straight away, but we did a bridging course and were both offered a place. It shows that if the right support systems are in place for Aboriginal people, we can achieve what we want. We have the ability, but education and support are crucial to achieving good outcomes.

We have four children, we were 19 when we had our first baby, but we both went to UNSW and they were amazing. If it wasn’t for those systems, and scholarships, and people who really believed in us, we might not be where we are. We’ve had quite a journey. Our lives could have been completely different. I see a lot of young Aboriginal people in the criminal justice system and I think they could easily be doing what I’m doing. A lot of them just haven’t had the opportunities in front of them, or taken them.

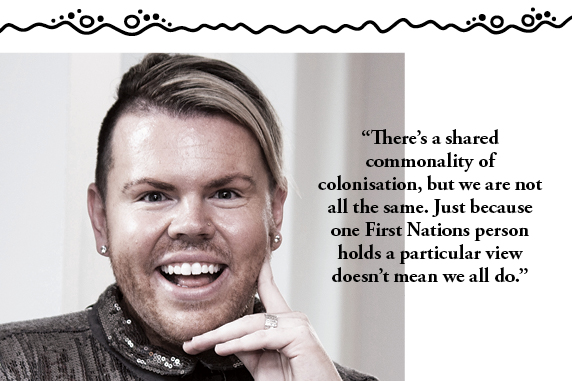

Trent Wallace

Trent Wallace is an Indigenous man who grew up on Darkinjung Country, a First Nations Advisor, Pro Bono and Social Impact at Ashurst. He’s the first and only Aboriginal person to occupy this role in a global law firm and is passionate about educating legal professionals about Indigenous peoples and the law and promoting Indigenous voices. Wallace also lectures at his alma mater, the University of New England.

How can the law begin to address hurt from the past?

What question are we really asking here? I feel like it always comes down to, “What would it feel like to finally matter in Australian society?” The first thing is to acknowledge that we can’t be homogenised and assimilated. Addressing the hurt comes down to each individual First Nations person. We have different views, different experiences. There’s a shared commonality of colonisation, but we are not all the same. Just because one First Nations person holds a particular view doesn’t mean we all do.

You’ve said that often you’re the only Aboriginal person in rooms where Indigenous issues are being discussed. What are the main issues you wish the legal profession knew?

It’s a lot of pressure. For me, it’s like using the methodology of a handbrake, pulling people up, but with kindness. It’s taxing, it’s hard work, but I don’t know any different. Historically, I wouldn’t be allowed into such rooms, so we’re making some progress – albeit slow.

What do I wish people knew? It’s about being culturally aware, informing yourself, hiring people to come in and educate your firm, and embracing a learning journey. We need culturally aware practices; it needs to be embedded in the way we do business. Indigenous voices need to be heard.

We have expertise – especially in strategic and risk advisory – and that’s valuable. It’s what I call cultural due diligence. This is a profession based on expertise and learning, but you can’t get our knowledge from a degree or post-admission experience. It’s lived experience.

That’s an interesting one. You’ve also previously said that, as an Aboriginal male, you’re more likely to be imprisoned than formally educated. How has this lived experience impacted your work?

I don’t represent every First Nations person, nor could I, but there are a lot of stereotypes. People assume we only come from a place of deficit, but we’re rich in our culture, history and ancestry.

Ashurst has been very supportive; First Nations work here is just business as usual. It’s embedded into the DNA of the firm. It’s not something we need glossy promotion for, it’s just normal, and that’s a really good thing. Otherwise, we’re generally only invited to speak on designated dates – like NAIDOC Week. It’s an extremely emotionally taxing time, because people seem to ask, “Tell us how difficult your life has been and how triumphant you are?” Racism is also heightened around those times.

For me personally, I would’ve liked to be an entertainment lawyer or maybe a barrister. As a student, I realised there was such a gap in First Nations knowledge, the same Eurocentric principles being applied over and over again. I had to change career paths. I took up advocacy because of the work of the many First Nations warriors who came before me, so I could carry it forward. This work is far from done.