If high-profile estate cases estate can teach us anything, it’s that where there’s a will, there is often a day in court. LSJ explores this testy area of law.

Without leaning too heavily on the cliché about the two guarantees in life, the fact remains that most humans face a statistical likelihood of at some point coming into contact with or being a part of a will.

For plenty of people, the only direct experience they will have with the legal system will be in relation to a legal estate – either when they make a last will and testament, or when they must decipher the meaning of a loved one’s final wishes in the cloudy aftermath of their death.

So why, despite the inevitability of death and the necessity that we will have to pass on money, assets, or treasured mementos, are so many still so bad at building a watertight will?

A string of high-profile Australians have been the subject of Supreme Court stoushes about their messy estates. Such disputes can tear families apart.

So when deciding what becomes of what one leaves behind, what can lawyers and their clients learn from such stoushes in order to avoid similar scandal?

Where there’s a will …

It may be tempting for some to save on lawyers’ fees and pick up a cheap do-it-yourself will kit at a newsagency, but experts warn it is in everyone’s best interests to properly consider and map out one’s estate.

Under the Succession Act 2006 (NSW)¸ spouses and children are automatically eligible to make a claim for provision in the deceased’s estate but pretty much anyone else is free to challenge it. The challenger must be able to successfully prove their moral claim, and that the deceased had a moral duty to ensure they were provided for.

NSW has the most generous estate provisions of all states and territories, especially when it comes to notional estates. In the case of insufficient funds in an estate, a court can look to assets that were gifted by the will-maker during their lifetime for less than market value, or those held in structures that were controlled by the now deceased. Examples could include jointly-held property or a superannuation death benefit.

Jill Wilson and Ben White, who spent a year examining the case law relating to estate contestation in Australia, found many claims were being made by well-off adults. Many of them had high net wealth, and in one case they studied the claimant had a net worth of more than $1 million. Their study also found 75 per cent of estate claims contested in court were successful.

White says the findings concluded that “the balance needs to be struck” between allowing for adequate provision and negating claims from people who “even by very conservative estimates are financially comfortable”.

“It is a question of whether we are striking the right balance between testamentary freedom and providing for people who have a genuine need,” he tells LSJ.

“Our finding [of a 75 per cent success rate] raised the question of whether the framework, at that time, was too generous.”

But Wilson adds that wealth calculations are relative: “What some regard as comfortable others would regard as semi-poverty.”

Wilson also notes that some people believe the effort they made in caring for an elderly parent should be rewarded with a bigger slice of the estate pie.

“People cope with loss quite differently. A dispute over an estate can be a result of partly grief, partly anger, and the anger is often connected to things that have happened in the past,” she says.

“For others, they may feel they have had no recognition for the care they have given an elderly parent, when they were the only one of their siblings who provided that care.

“What is happening now is that some people might leave a letter acknowledging the care that child provided – in a way an explanation that they had no other option but to leave an equal share [of the estate] for all children. It may not feel like it, but the equal share is doing them a favour by preventing a challenge to the estate.”

Wills and estates expert Rod Cunich points out this area is of law is often not offered as a subject in many universities. He believes it should be.

“Simply, there are not enough lawyers who are deeply knowledgeable about this area of law to identify the potential risks,” Cunich tells LSJ.

“The vast majority of lawyers leave university with a law degree and no idea about wills and estates. Until College of Law, most are ignorant about this area.”

But estate litigation specialist Monica Ross-Maranik says there is sometimes little that can be done to make an estate completely watertight.

“It could involve having a conversation with family and friends, in making a will, as to how to divide up assets, and having a court sign off, but many would consider that a fairly morbid approach and perhaps also hitting a nail with a sledgehammer,” she says.

“The other option is to die with no estate and to divest all of your assets in the three years before death. But taking this approach also requires a total trust in the people [the assets are divested to], and human nature is that sometimes people do the wrong thing.”

There’s a way …

Cunich says the high rate of successful estates claims contributes to “fertile ground” for lawyers to run cases, even though taking a case to the courtroom may drain the money being fought over in the first place.

However, he says that for many, the fight is worth it. He points to the exploding property market, especially in Sydney, and superannuation to explain how modern estates are becoming far more lucrative.

“With property prices today, for most people who have owned a home and accumulated super, there can be $1 million-plus in their estate,” he says.

“In a case of a first marriage, this could be a divorce going back 20 or 30 years, someone may believe the ex-partner and children were effectively provided for as a result of the [matrimonial] settlement. Sometimes it can be purely emotional and someone believes their [children from the first marriage] have already had their bite of the apple.”

Often people may have earned the bulk of their wealth during a later marriage and feel those family members are “more deserving” of the estate.

“Consideration will be given to the value of the estate, as well as the wealth of each person who is benefitting,” says Cunich.

This applied in the estate of Australian cricket legend Richie Benaud, whose long-time wife Daphne lived in a waterside property while his ex-wife and son were residing in public housing.

A battle of wills

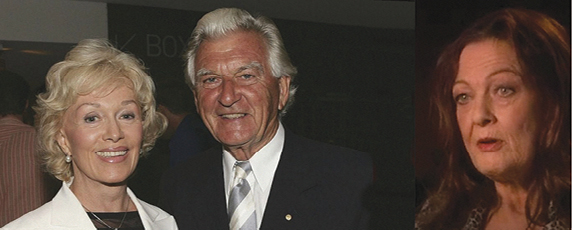

Bob Hawke

It is understood the former Prime Minister’s daughter Rosslyn has engaged family lawyers ahead of a challenge to his estate, which left everything to his long-term second wife Blanche d’Apulget. All of Hawke’s children received $750,000 in a payment from d’Apulget following his death as per an attachment to his will.

Katharine Howard Olson

Prominent Australian artist John Olson won a legal battle against his stepdaughter earlier this year, after a court determined Karen Mentink secured a $2.2 million payment from her mother, John’s wife Katharine, through “unconscionable conduct” two months before Howard Olson died from cancer.

Richie Benaud

Benaud’s wife Daphne was sued by his first wife Marcia and eldest son Gregory, who asked the court to make provision for their “maintenance and advancement in life.” At the time both were living in public housing. The case settled before trial after the trio agreed on a payment to be made to Marcia and Gregory.

Neville Wran

The children of the former NSW Premier settled their dispute over his multi-million-dollar estate in mediation. It followed a battle between the daughter of his first marriage, Kim Wran-Sheftell, and his two children from his second marriage, Hugo and Harriet. The case settled as Harriet faced court for her role in a murder over a drug deal.

“A court might well [ask] why a person who doesn’t need to ends up on Centrelink when a wealthy family member could have made provisions for them,” Cunich says.

Ross-Maranik believes this is appropriate. “Should the public purse be burdened when somebody else could support them?” she asks.

“People should be entitled to bring a claim that they are entitled to a share of an inheritance, and I don’t think the taxpayer should support people who could be provided for – it’s why we should have family provision.”

When other children have modest but satisfactory incomes, Ross-Maranik says it is often the “lame duck” of the family – who may have received more money from their parents during their lifetime – who will benefit the most due to their clear dependency.

“There are often big dollars involved, and that level of wealth breeds litigation,” she tells LSJ.

“People are living longer. Traditionally, people receiving an inheritance were once in their 40s and they would buy a house outright from that money. Now people in their 70s – who in a sense have been holding out for this money to pay off a mortgage or something like that – are the ones now looking for family provision.

“If someone is considering leaving someone out, the decision needs to be made as to whether to exclude them outright or to leave them something that may or may not be considered adequate.

“If someone is left something, obviously there is a chance they can challenge it and a court can find it was not adequate. But it is a much easier leap to challenge if they are just left out entirely.”

When a stranger calls

Cunich offers an example of an older couple who retired to a regional town and assisted a struggling man with accommodation in return for help on their property.

“He had helped them with their cottage and they had allowed him to stay in exchange for mowing lawns and doing odd jobs around the farm” Cunich says.

When they died, the man was found by a court to have a moral claim on the estate, as he had come to rely upon them during their lifetime; a decision that most likely surprised the couple’s surviving adult children.

“It was clear to me, based on the Act, that he was going to win something. It shows how complicated it can be and why it is so important to get proper advice. It is multi-factorial and a litigator’s delight.”

Estates and elder abuse

While the Succession Act might be causing heartache for those who would prefer to assign their assets to those they felt gave them the most care and love, it also provides a safeguard against the emerging scourge of elder abuse.

The Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) estimates that as many as 14 per cent of Australians aged 65 years and older experience some form of abuse every day. In a similar vein to family violence, elder abuse is likely to go underreported.

As the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety drags this often-hidden form of abuse into the light, a new report suggests more evidence is needed to determine the effectiveness and suitability of emergency shelters or crisis helplines, which could become a last resort for those facing threats from relatives or others to amend their will.

In some cases, children have sought to get a certificate from a dentist to certify that their parent has the required mental capacity to make changes to the will, when other doctors have refused to verify it.

The Australian Law Reform Commission found that “while elder abuse often occurs in a family context, it is a broader phenomenon than family violence”.

The AIFS report identified risk factors for perpetrators, including the stress and burden on caregivers. Older persons with a cognitive impairment are at higher risk of experiencing elder abuse.

“Perpetrators of abuse are more likely to depend on an older person in various ways – emotionally, financially, housing – than non-perpetrators of abuse,” the report found.

“In some cases, such relationships of dependency have been described as ‘parasitic’, where an adult child with associated risks lives in a dependent relationship with their older parent.

“Among the barriers to reporting are fear of retaliation, embarrassment, shame and fear of consequences for adult children if they report the abuse.

“There is a need to take seriously the economic and social demands of an ageing population, while avoiding disempowering people that can lead to forms of elder abuse.”

The AIFS report urges more should be done to build the evidence base on interventions that could support older persons who are not living in care and may be suffering abuse from a family member.

The NSW Government recently appointed the state’s first independent Ageing and Disability Commissioner, Robert Fitzgerald, to investigate the rise of elder abuse and ways to combat it. Fitzgerald has powers to initiate investigations into allegations of abuse, neglect or exploitation, as well as compel individuals and organisations to provide information regardingthose claims.

Challenges under the Succession Act 2006 (NSW)

Steinmetz v Shannon [2018]

The court held that the deceased had left adequate provision for his widow’s “proper maintenance” after she sought an altering of his will, which left the bulk of his estate to the children of his first marriage. Pembroke J remarked in the judgment: “She will not have the benefits, the security, the holidays, the comforts and the additional financial advantages that she enjoyed during her relationship with the deceased. But as a matter of law, should she be entitled to expect more?” In May the NSW Court of Appeal overturned the decision.

Sgro v Thompson [2017]

The court held that the adequacy of provision in a will is not to be determined solely by reference to a claimant’s poor financial circumstances. White JA said: “The deceased will have been in a better position to determine what provision for a claimant’s maintenance and advancement in life is proper than will be a court called on to determine that question months or years after the deceased’s death, when the person best able to give evidence on that question is no longer alive.”

Lodin v Lodin [2017]

The court held the factors relevant to whether a claimant, in this case the former spouse, is ‘a natural object of testamentary recognition’ must not be conflated with factors determining if a family provision order should be made. The CCA determined she did not establish the factors to warrant such an application. The marriage had ended 25 years earlier, and the residual moral obligation was discharged by a divorce settlement and the deceased’s unfailing child support payments.

A change of heart, a change of estate

In the twilight years, a new romance might be reflected in an older person’s estate and there is little the surviving children can do.

“The question is who has the dependency issue, because the courts don’t necessarily state that in the definition,” Wilson says.

“Someone might meet another resident in a nursing home, and they get married. Then one of them dies a year later and everything has been left to the new husband or wife. That one year [of marriage] might have been the happiest of their life, but the kids may not see the relationship that way, and then the issue of equal share and appealing the distribution arises.”

Ross-Maranik says it is difficult for an estate to truly reflect “the fluidity of relationships over a lifetime”.

“With blended families, and children from multiple relationships, there is a natural tension that exists in those two pools of beneficiaries.

“And if something is left out, they feel like their parent didn’t love them like their other kids.”