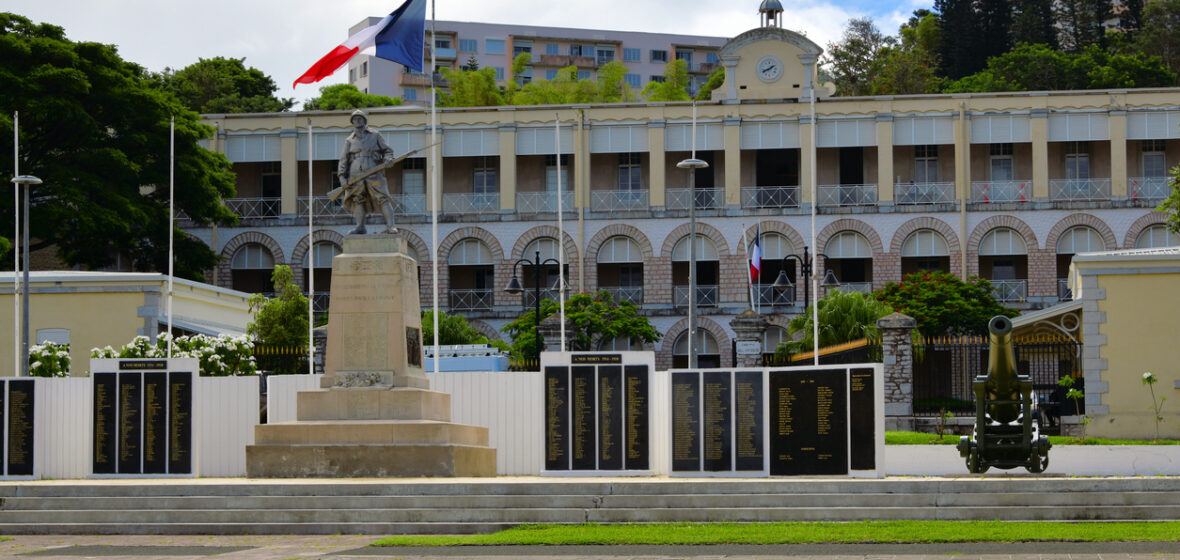

A state of emergency and curfew was declared last week in New Caledonia, which has been a French territory since it was colonised by France in 1841. Officially a French overseas territory since 1946, New Caledonia lies between Australia and Fiji in the Pacific Ocean, though it has not been a focal point of Australian media attention until current events unfolded.

For decades, debate has reigned over whether the islands should be part of France, autonomous or independent. The responses are largely divided by attitudes to colonialism or decolonisation.

When Paris announced plans in January to impose new voting rules that could give tens of thousands of non-Indigenous residents voting rights, along with introducing national legislation to defer local elections due in April 2024, it resulted in a violent uprising in Noumea that has resulted in six deaths and around 200 arrests. Indigenous Melanesian peoples, Kanak people have lived on the archipelago that would later become New Caledonia for thousands of years and they make up nearly 40 per cent of New Caledonia’s population, along with sizeable Vietnamese and Polynesian communities, and pro-independence groups say any such change to voting rules would dilute the Kanak vote.

The new laws allow French residents who have lived in the archipelago for at least 10 years to vote. Voter eligibility restrictions ensuring only longstanding residents could vote in local elections was a precondition for Kanak leaders to formally end civil disturbances from 1988. This followed years of French immigrants into New Caledonia to skew the vote away from independence.

Visiting Fellow at ANU Centre for European Studies, Denise Fisher, was an Australian diplomat for thirty years. Following diplomatic missions as a political and economic policy analyst in Rangoon, Nairobi, New Delhi, Kuala Lumpur and Washington DC, she was appointed Australian High Commissioner in Harare then Australian Consul-General in Noumea, New Caledonia in 2001. Between 2001 and 2004, her work covered the French Pacific territories.

She says this move by the French government was not a surprise, since Macron had signalled his intention late last year.

“All the independence leaders had sent people to Paris to lobby against it, and it was widely known that this was a core issue for the Kanak people. This is not something new, it goes back to their longstanding demands for independence. 40 years ago, who could vote in local elections was at the root of the peace agreements. Everybody made huge concessions: the state, the loyalist parties that want to stay with France, and the independence parties. One of the foundational compromises that the Kanak leaders secured for the last 40 years was a special definition of who could vote in local elections, which since the agreement in 1998 had required 10 years residence from that time.”

Fisher says, “In the 1970s, there was an overt French policy, fully acknowledged by the French, to bring in people from other parts of France simply to outnumber the Kanak. So, the issue that Mr. Macron has chosen is very deep seated, the most delicate issue. And don’t forget it’s also the most important issue for the loyalists and loyalist parties. They want to roll this [special definition] back because it’s obviously given an electoral advantage to the indigenous people who are not going anywhere, whereas the European population sort of comes and goes.”

On May 19, the presidents of four other French overseas territories signed an open letter calling upon France to withdraw the voting reform plans (La Reunion in the Indian Ocean, Guadeloupe and Martinique in the Caribbean and Guyane in South America).

The letter stated: “Only a political response can halt the rising violence and prevent civil war…[we] call on the government to withdraw the constitutional reform bill aiming to change the electoral roll … as the precursor to a peaceful dialogue.”

Around 1,000 security forces began reinforcing the 1,700 officers already on the ground from Thursday. On May 21, Australia and New Zealand sent planes to New Caledonia to evacuate the approximately 3,000 tourists unable to access commercial flights, which have been disallowed from the main airport.

The Matignon Agreements

On June 26 1988, the Matignon Agreements were signed in the Hôtel Matignon by loyalists to the French government who wished to keep New Caledonia within the French Republic, Jean-Marie Tjibaou and Jacques Lafleur, and separatists who opposed this. The agreements resulted from negotiations arranged by the French government. The 10-year accords led to a period of institutional and economic development that made provisions for the Kanak community in return for an end to demands for independence.

At the finality of the Matignon Agreements, the Nouméa Accord was signed on 5 May 1998, enabling a further 20-year period of transition prior to votes on sovereignty in 2018. It aimed to address long-running tensions between the Kanak and the French government. The Accord promised to give increased political power to Indigenous people. However, following three referendums to determine whether New Caledonia would remain part of France or become its own country, independence from France was rejected in all. The result was that France continued to control New Caledonia’s military, immigration, foreign policy, economy and elections.

In December 2021, France held the final of three independence referendums in accordance with the Noumea Accord. The Kanak communities were suffering from Covid deaths in their communities, and despite their protestations and eventual boycott of the referendum, it went ahead. This resulted in 3.5 per cent of pro-independence votes, significantly less than the 43.3 per cent and 46.7 per cent in the first two referendums.

Forty years ago, New Caledonia was also the hub of violent protests when the pro-independence Kanak and Socialist National Liberation Front (Front de libération nationale kanak et socialiste, or FLNKS) boycotted an election and set town halls alight. Four years of civil war followed from 1984.

Australia had initially supported the Kanak independence movement but by 19 November 1984, then Foreign Minister Bill Hayden asserted that violent uprisings would result in Australia losing ‘immense sympathy’ with the Kanaks.

Fisher recalls her time in New Caledonia between 2001 to 2004 as a time of optimism, which may since have been tempered by the way the agreements within the Noumea Accord played out.

“I was there in the first mandate of the 5-year congress and it was fabulous then. There was a collegial government, or the cabinet of the local government. There were members of the cabinet from the loyalist side and independent side, as there are today, and at that time, loyalists outnumbered Kanaks. There was a loyalist president and a Kanak vice president, and they attended functions and official events side by side. The [Noumea Accord] agreements worked well for 30 years, but then the final of three independence referendums ended that. In the first two, the French organised the referendums in a very impartial way in 2018 and 2020,” she says.

“But in 2021, it was not impartial. Even during the campaigning, there were publications put out by the French state patently siding with loyalists. When they set the date, it was the height of Covid, and the main impact of the deaths was in the Kanak community. There were 300 deaths and even for one death in the Kanak community, there are lengthy mourning rituals. So, they asked to delay but the Defence Minister Sébastien Lecornu went ahead with the vote and since then, Kanak have rejected the vote and want another.”

Fisher says the protestors are largely the young Kanak, who have been squeezed out of the education system and the economy, which is modelled on the French system.

“The Noumea Accord was remarkably successful, going swimmingly, but the young Kanaks were kept out of the economy, and they dropped out of the very strict French system of schooling, which often required them to travel far from home to live in boarding schools, so there’s been a building resentment and frustration amongst Kanak youths. Kanak leaders called for an end to violence after two days but the youth kept going. The French have sent 2000 reinforcements to the 500 normally there, but the violence just keeps going.”

On 23 May, Macron met with the pro-independence President of the Government of New Caledonia Louis Mapou and the President of Congress Roch Wamytan in Noumea.

Fears of a ‘domino effect’

Fisher says that “French Polynesia, historically, has always wanted what New Caledonia has got. They got a special statute in 2004, and they have a lot of the autonomies New Caledonia has got, but not all of them.”

“The Noumea Accord was remarkable in the number of changes the French state made to give more autonomy to New Caledonia. They changed the French constitution to provide for the voter eligibility provision in 1998. Then 22 French parliamentarians from overseas territories wrote to the President and said, ‘you need to withdraw this legislation for peace to be re-established’, and a number of independence leaders from French overseas territories said the same thing,” she says.

“What will be important for governance, and the institutions in New Caledonia will be what happens now and what they define for their future. Certainly, what happens in New Caledonia will have an effect on the other territories France has as possessions.”