People from diverse communities explain how their cultural background shapes their views on including the Voice in the Constitution.

An invitation to walk hand in hand

The Desis for Yes campaign was launched at the start of July 2023 by members of the Indian diaspora in Australia. Co-convenors Nishadh Rego and Khushaal Vyas, both of South Asian heritage, shared with LSJ the campaign’s objectives and the reason each is involved.

Rego is a first-generation Indian-Australian and the Co-Chair of the Sydney Alliance.

“Desis for Yes,” says Rego, “is an initiative that seeks to strengthen understanding of and engagement with the upcoming Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum and the Uluru Statement from the Heart within South Asian diaspora communities.

“Many of us are interested in the upcoming referendum and inevitably have questions about what it means and what its consequences will be. We are talking with families, communities, and businesses to deepen understanding of the referendum among South Asian Australians, so that community members are well informed ahead of the vote.

“Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians are our first peoples and have been custodians of these lands for 60,000 years. The ancient connection to the land is a fundamental part of our country’s story and warrants constitutional recognition for Indigenous Australians.

“A constitutionally enshrined voice to parliament will give Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians a means to advise our elected representatives on how to address long standing issues that affect them, many of which stem from the legacy of colonialism. Its constitutional quality will ensure that the Voice is not subject to the vicissitudes of party and electoral politics.

“So many diaspora communities have endorsed the Uluru Statement from the Heart and accepted its generous invitation to walk alongside our Aboriginal and Torres Islander sisters and brothers on the journey towards Voice, Treaty, and Truth. The journey itself will make us a stronger and more mature nation.”

‘The journey itself will make us a stronger and more mature nation.’

Vyas, formerly a commercial lawyer, is currently working in the community legal sector. He says, “South Asian Australians are proud Australians and share a passion for justice and improving the lives of Indigenous Australians. However, many have not had the opportunity to learn about the history that has resulted in the intergenerational trauma and significant barriers that Indigenous Australians still face. It’s a history that South Asians can empathise with given the impacts of colonial rule are still felt in the subcontinent today.

Vyal says, “With all non-Indigenous Australians having been benefactors of Indigenous dispossession, informing the wider community, combating misinformation and standing in solidarity with Indigenous Australians is a significant step we hope Australians of all backgrounds will take together to ensure ATSI communities are meaningfully recognised in the constitution and are able to have a say on the issues impacting them.

“The Uluru Statement from the Heart generously invited Australians of all backgrounds to join them on this journey. Through Desis for Yes, we are proud to take up that invitation and walk hand in hand with Indigenous Australians to play our role in bringing in a positive new chapter for Australia.”

‘We are proud to take up that invitation and walk hand in hand with Indigenous Australians.’

Our backyard, our responsibility

Mark Leibler is a tax and corporate strategy lawyer and Senior Partner at Arnold Bloch Leibler.

His interest in the Voice comes from two places, he says: both personal and professional.

“Even as a boy, I had a sense that the law and the overriding principle we understand and accept in the community as the rule of law are fundamentals of civil society.

And while I was attracted to the idea of knowing more and being part of that system, regardless of whether I’d end up practising law, I knew that the reasoning process I would pick up as a law student – the ability to order and structure – would be of great value.

More than half a century later, I’d say that all my success and pleasure in the law has been afforded by the revelation I had towards the end of my articles that I could – indeed I should – shape my career in the law in a way that worked for me personally.

I’ve been able to pursue my passions and interests both inside and outside of the law to leverage a most rewarding career and life.

I graduated from the University of Melbourne’s Law School in 1966 with a first-class Honours degree and the year’s Supreme Court Prize. Nevertheless, it was clear to me that no mainstream Melbourne law firm was going to take on a Jewish articled clerk.

It was a reality of life at the time and, ultimately, a blessing in disguise, because I was taken on by Arnold Bloch in his sole practitioner firm, alongside his associate Ron Merkel. Arnold taught me, by example, what makes a great lawyer, how to build a great firm culture and the imperative of meeting, indeed exceeding, client expectations. Both Merkel and Arnold as my first legal role models, had a strong sense of the law as an instrument of social justice and of the need to serve the public interest alongside the profit motive.

The firm established a public interest law practice with a focus on Indigenous human rights and empowerment. This practice, a great strength of the firm, grew from our supported for a range of community causes over the years.

In 1993 we were invited to represent the Yorta Yorta people of north-eastern Victoria and southern NSW in what became an epic battle for native title justice.

The story of the Yorta Yorta, and what I learned about the history, culture and suffering of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, was nothing short of a revelation for me.

When I was a boy, growing up in Melbourne, we learned nothing at school about Australia’s Indigenous history. Before we took on the Yorta Yorta case, I was not aware of having met an Aboriginal person, let alone the extent of the continuing injustice Indigenous Australians were suffering, how they had been scarred by dispossession, disrespect and racism – the same weapons that have been used against the Jewish people for millennia.

My sense of the ties between the Jewish people and Aboriginal people grew even stronger through my friendship with Noel Pearson, who was articled to me after graduating as a lawyer. Noel says that the time he spent at Arnold Bloch Leibler taught him how much our two peoples have in common and his main take-out from working with me and meeting many Jewish Australians was that, like us, Indigenous people can and must resist victimhood, as Jewish people have done, even in the face of persistent racism and victimisation.

This is where the Voice to Parliament comes in. There is no better country on earth than Australia. It’s given me a great life but there is one undeniable failing in terms of the brutal treatment inflicted on the nation’s Indigenous peoples, and we have an obligation to do something about it.

Of course, there are terrible things happening to people all over the world, but this is our backyard and it’s our responsibility.”

‘There are terrible things happening to people all over the world, but this is our backyard and it’s our responsibility.’

You need to step into the room

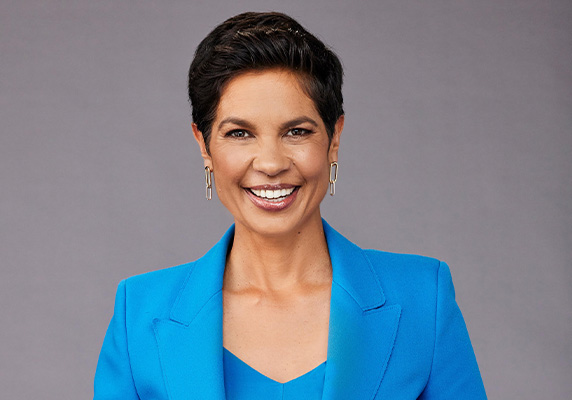

Narelda Jacobs, a Whadjuk Noongar woman from Perth, is a television presenter and journalist. Jacobs has experienced the full range of emotions, from the Uluru Statement from the Heart in 2017 to when the referendum was formally put on the agenda during Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s victory speech in May 2022.

“When it first looked like the referendum was coming up, that the Voice might become a reality, there was so much hope,” she says.

“That was six years ago. I read the Statement from the Heart, and there was so much hope. Then came negative comments about it, comments from politicians that there was no chance of its succeeding.”

“And so we had years in the wilderness – until the last election,” Jacobs says. “I was in the newsroom on election night, and I heard Prime Minister Anthony Albanese talk about the Voice in his speech, and it really it moved me to tears.

“I felt such elation, elation that the ancestors are going to be listened to, that the fight hasn’t been in vain.”

Jacobs adds, “that’s my feeling about the Voice to Parliament: that we have this chance. This is our best chance now, and we can’t waste it.”

A society with the Voice in place, with its recommendations acted on, “that society would look like the United Nations,” Jacobs says.

“Imagine, if you can,” she continues, “imagine all the First Nations in Australia being on the Voice to Parliament, each from their own nation.

Jacobs offers a comparison to the countries of Europe. “If you look at Australia and imagine Europe,” she says, “the Yolnu nation might be France, the Yamaji nation in WA would be Italy, and so on. Our First Nations are as big as whole European countries – that’s the comparison I’m making. Each with their different wish lists.

“But there would be commonality: the effects of being listened to.”

“And saying what is needed in their own country. All of the First Nations in Australia are different because of where they are, the types of food they have, the seasonal changes they experience.

“And that’s just the physical and the geographical elements of it.

“Then you’d have the different land usages. The interest in mining, whether it’s pastoral country, whether it’s islands, such as the islands of the Torres Strait, whether you’re impacted by climate change, whether that’s an immediate threat.

“I think I’d envisage a meeting of all the First Nations,” Jacobs concludes, “a meeting of people from all over this country, each with their own unique needs and wishes for what will make their Country better.”

‘… a meeting of people from all over this country, each with their own unique needs and wishes for what will make their Country better … but there would be commonality: the effects of being listened to’

“And in each nation,” she continues, “there are some issues with detention, imprisonment; there are child protection issues and health issues. There are so many issues like these, and the commonalities are the gaps that need closing.

“And I would love to see the way each representative is consulted as knowing about their own homes, their own lands, because this would be a powerful tool: someone with that direct ear who also has a direct voice to government. That is such a powerful tool.

“Those people who are our elected representatives are going to be the ones to unite us and make it possible for us to learn so much from each other as well.

“The beauty of the Voice to Parliament is that it would show the will of all the people.”

“We all need to be active in standing for this change,” Jacobs adds. “You need to step into the room in order to change it. The halls of power are a place we should definitely be stepping into. Look how beautiful that space is now with the number of women, and the number of people from diverse backgrounds who are there.

“And that wouldn’t have been the case if the first woman hadn’t walked in there. We all need to be there, and we also need to remember that the visual of everyone being there together in the halls of power is very important.”

‘The halls of power are a place we should definitely be stepping into. Look how beautiful that space is now with the number of women, and the number of people from diverse backgrounds who are there.’

The impact of displacement and injustice

Solicitor Sawathey Ek says that people from a refugee background like himself support the Voice, seeing it as an “opportunity” for those who have suffered “the loss of identity, the non-recognition of status and the loss of your sense of value.”

Ek is Founder and Spokesperson of the Australian–South East Asian Network, which has enabled members of the Lao, Cambodian and Khmer Krom communities in south-west Sydney to come together to advocate to governments on behalf of multicultural groups in Australia, as well as citizens in their homelands.

Admitted to practice almost 25 years ago, Ek is principal of western-Sydney based EK Lawyers. For the past 15 years he has campaigned for the rights and opportunities of refugee and migrant communities, representing clients in human rights cases, and engaging with federal parliament on humanitarian issues at a national and international level.

Ek was 14 when he came to Australia with his family in 1983 as one of the 12,000 Cambodians who sought refuge in this country between 1979 and 1986. He speaks of himself as “someone with the bitter experience of life in a Cambodian refugee camp in the ‘80s, and with memory of a profound loss, being displaced as a result of civil wars under successive genocidal regimes led by Pol Pot and then being under the dictatorship government of Mr Hun Sen”.

Ek’s parents, who survived the Khmer Rouge reign under Pol Pot, instilled an indelible work ethic in their son. His father was an Indigenous Cambodian, from the Khmer Krom people, who lived in what is now known as the South Mekong Delta in Vietnam. Ek’s father fled to Cambodia in the 1940s, then to Thailand in 1979 and eventually to Australia, so Ek is acutely conscious of “the generational impact of displacement and injustice”.

Ek’s father, as with most Indigenous Cambodians, was given a Vietnamese surname designated specifically to identify Khmer Krom families. The Khmer Krom were regarded as an unrepresented nation. “The policy of forcing the adoption of a new heritage and identity inflicted generational hurt,” says Ek, who sees clear parallels in this with Australia’s Indigenous communities.

In recent years, Ek’s focus has shifted towards advocacy on national issues he sees as impacting on communities with lived experience of oppression. The Voice is one such issue, he believes. And, far more than an important constitutional debate, this is deeply personal to him.

“Supporting a Voice for First Nations peoples is the least I can do. My father would have been pleased to know that his belief in humanity has lived on through my advocacy. I believe leadership on this issue starts from inside our home,” he tells LSJ.

“If compassion and inclusion are [what characterise us] as Australians, then a Voice to Parliament for First Nations (people) is an opportunity for us to promote inclusion. As refugees from civil wars and dictatorial regimes, we were deprived of the fundamental rights and freedoms we are seeing now as being promoted by Australian society.”

These freedoms and rights, he says, should be extended to First Nations people. Though his own family and other refugee families were able to migrate to Australia and find a work and home, Indigenous people face structural disadvantages.

From age 14 Ek lived in Australia in public housing and was a recipient of a humanitarian scholarship to Sydney Grammar School in 1987. He graduated with honours in law in 1993 from Bond University when he was 24, just ten years after arriving in the country.

Prior to his admission as a lawyer, he founded the Khmer Krom Cultural Centre of NSW. In 1998, the then Justice of the High Court Michael Kirby became patron of the centre, a position he still holds.

Ek believes that “in order for our nation to move forward and promote multiculturalism, we must first recognise that the intention of the Voice is to bring some closure” for past injustices that have left Indigenous communities behind.

Ek refers to the concern expressed by some that “singling out Indigenous people for a voice could fragment society, with preference given to a particular racial background.” He adds, “people are saying that the Voice would re-racialise Australia and make some people more equal than others,” he says.

But, Ek says, those who call for the proposed Voice to include a multicultural voice are missing the point. “It’s a misguided conversation inferring an element of competition I believe is unhelpful and unnecessary – it serves no purpose,” he adds.

Ek says that to parallel the situation of multicultural communities with that of Indigenous communities is to imply that “multicultural communities suffered [the same] oppression and violence in Australia that Aboriginal peoples did during those years of colonisation.”

“The least we can do,” he says, “is to contribute to a positive debate, as opposed to being seen as competing with First Nations peoples.”

Having the opportunity to take part in this national discussion about the Voice, he adds, gives him “a sense of liberation and recognition”.

As the referendum draws closer, Ek pleads for empathy from those who remain unsure about or fearful of the proposed constitutional change. This is a plea to “imagine you and your ancestors have experienced violent policies of discrimination, exclusion and denigration of basic human rights.”

Unless we promote the inclusion of the Voice in the Constitution, Ek says, “we will continue to serve Australia’s First Peoples with injustice.”

Ek ‘s perspective was developed from a story by writer Jen Cowley. LSJ thanks Cowley for permission to incorporate it here.