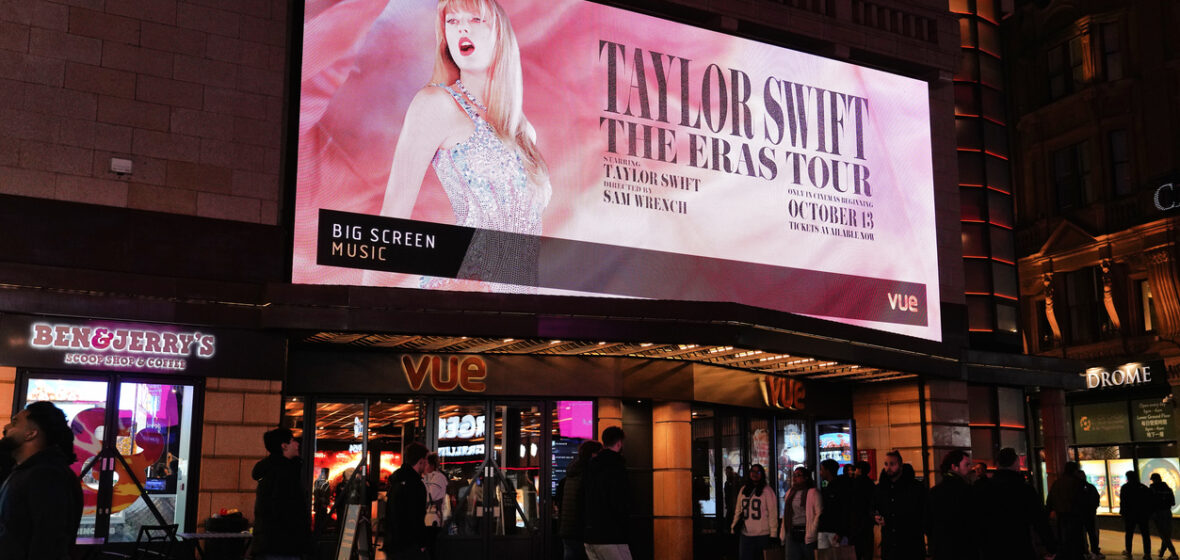

The issue of deepfake pornographic material has been thrust into the spotlight as a result of a high-profile celebrity being targeted and exploited by predatory creators.

Artificially manipulated images of Taylor Swift, which depicted the singer in explicit pornographic material were distributed via X (formerly Twitter) and Telegram, receiving more than 27 million views before the account posting images was suspended 19 hours later.

X responded publicly, claiming it was removing the images and denying users the ability to search for “Taylor Swift”, “Taylor Swift AI”, and “Taylor AI”.

Rather than X, it was largely Swift’s fans that were responsible for the removal of the images. Her fans reported accounts that were sharing the images, resulting in the suspension of offending accounts and removal of the explicit images.

As reported by the BBC earlier this month, a 2023 study by homesecuritiesheroes.com revealed that since 2019, there has been a 550 per cent increase in the creation of artificially altered images. Pornographic images make up 98 per cent of artificially images created and distributed and 99 per cent of the victims are women.

In the wake of the Taylor Swift event, US lawyer Carrie Goldberg, who has represented victims of non-consensual sexually explicit material, told NBC News that tech companies and platforms fail to prevent deepfake images from being posted and shared online, despite rules against this.

“Most human beings don’t have millions of fans who will go to bat for them if they’ve been victimised,” she said.

“Even those platforms that do have deepfake policies, they’re not great at enforcing them, or especially if content has spread very quickly, it becomes the typical whack-a-mole scenario.”

She added, “Just as technology is creating the problem, it’s also the obvious solution. AI on these platforms can identify these images and remove them. If there’s a single image that’s proliferating, that image can be watermarked and identified as well.”

Federal criminal and civil penalties for deep fake sexual imagery

While increased criminality of the sharing of non-consensual sexual imagery should theoretically deter or stop the production and dissemination of this material, there has not been a concurrent increase in prosecutions. This suggests the gaps and loopholes in existing legislation and the way it is enforced. Currently there are only civil penalties provided for in the federal laws, rather than criminal.

On January 23 2022 the Online Safety Act 2021 (Cth) came into effect, particularly to address the rise in sexual imagery as a form of abuse. Civil penalties for the non-consensual sharing of intimate images, including images which have been altered, are provided as Part 6 of the Online Safety Act, with a maximum civil penalty for the distribution or threat of distribution of such images set at $111,000.

While there are state-based criminal penalties for the creation and dissemination of non-consensual sexual images for those over the age of 18, there are no specific federal criminal penalties.

NSW, alongside all the other states except Victoria, includes altered – or deep fake – imagery within criminal laws.

Under the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth), there are various offences prohibiting the creation, distribution and access of sexual material depicting children. The Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) makes it an offence to “produce, disseminate or possess child abuse material” in section 91H. The offence carries a maximum 10 year prison penalty.

eSafety Commissioner enacts powers

Julie Inman Grant is currently serving her second five-year appointment as the eSafety Commissioner. Under the Online Safety Act, the eSafety Commissioner is empowered to issue a removal notice to online providers including Instagram, Facebook and YouTube, which require those platforms to remove the intimate imagery within a determined time frame (usually 24 hours) and to impose penalties upon the platform if it fails to comply with the removal order.

Grant told LSJ, “Deepfakes, especially deepfake pornography, can be devastating to the person whose image is hijacked and altered without their knowledge or consent, no matter who they are.”

“The rapid deployment, increasing sophistication and popular uptake of generative AI means it no longer takes vast amounts of computing power or masses of content to create convincing deepfakes,” she said.

“As a result, it’s becoming harder and harder to tell the difference between what’s real and what isn’t. And it’s much easier to inflict great harm.”

For that reason, acting on existing risks is as much of a focus as keeping an eye on potential new threats to online safety.

Grant said, “eSafety strives to be an agile regulator because we know that technology – and the creative ways humans inevitably find to misuse it – will always outpace policy. When we launched our first deepfakes tech trends brief more than two years ago, we foresaw the potential harm of this technology and ensured this was covered in the Online Safety Act and our image-based abuse scheme.”

Grant said they have received a small number of complaints relating to child sexual abuse material, deepfake imagery designed to bully the subject, and deepfake pornography.

“We find that most of the people who report image-based abuse content to us don’t want to go to the police or face a perpetrator in court, they just want the content taken down,” she said.

“Through our complaint schemes, we can provide and alternative pathway and real help to Australians who fall victim to a range of online harms, including image-based abuse. We have a 90 per cent success rate in getting this distressing material removed by informal means.”

Importantly, the perpetrator is not simply asked to comply with a removal order and free of liability once this order is made.

“We are also already taking remedial action against those who are weaponising generative AI to create deepfaked porn of both prominent and everyday Australian women,” Grant said.

“eSafety has commenced civil penalty proceedings against one such perpetrator, and these proceedings are ongoing. But a greater burden must fall on the purveyors and profiteers of AI to take a robust Safety by Design approach so that they are engineering out misuse at the front end. We’re not going to regulate or litigate our way out this – the primary digital safeguards must be embedded at the design phase and throughout the model development and deployment process.”

Grant believes the onus falls upon the platforms to step up their technological capacity to match the perpetrators using their platforms to create and disseminate offensive material.

“Platforms need to be doing more to detect, remove and prevent the spread of this extremely harmful content,” she said.

A successful removal

Grant says that once a report is made by a victim or their representative, eSafety can intiate an investigation “to determine whether the content constitutes image-based abuse, and potentially use our powers and a graduated set of powers to determine the best course of action to alleviate the harm.”

She explains that “this could include compelling removal of the material, requiring a perpetrator to take remedial action or, in especially serious matters, applying for an injunction to restrain a person from engaging in conduct that contravenes, or requiring them to take steps to avoid contravention, of the Online Safety Act.”

Even when content does not qualify as image-based abuse under the eSafety scheme, they provide advice and information about available avenues of support, including counselling and legal services.

“We recently received a complaint from a female in relation to threats and intimate images of her posted on social media. She told us she had been in a relationship during which her male partner took intimate images of her, including photos and videos,” Grant said.

“When the relationship broke down, the man started posting intimate images of the woman online. Initially, she was successful in having them removed but her former partner created further social media profiles on multiple online platforms to send her intimate images to current and prospective employers and others in her social circle.”

eSafety investigators were able to substantiate who the perpetrator was and a remedial direction was issued to him. Following the direction, the man removed the online accounts that had been used to post the intimate images and Grant says he is complying with eSafety’s directions.

“It’s hard to imagine how the woman in this example could have regained control of her intimate content – and her life – without the assistance of a scheme like ours, highlighting the importance of citizen-focused regulation,” she said.

That perpetrator, Antonio Rotondo, was later arrested and jailed for creating deepfake pornographic images of children and teachers at a particular Brisbane school along with violations against several women. The story was reported by the ABC in December 2023.

A spokesperson for eSafety says, “Our civil proceedings in the Federal Court centre on his failure to comply with directions from eSafety to remove image-based abuse content from his site that was reported to us by a number of Australian women.”

NSW addresses altered intimate images and ‘revenge porn’

In 2017, NSW introduced reforms to the criminal laws to target “revenge porn” or “intimate image abuse”.

Section 91P of the Crimes Act penalises the non-consensual intimate recording of a person with a maximum 3-year prison term and/or an $11,000 fine. Section 91Q and Section 91R respectively apply the same penalty to anyone intentionally distributing a non-consensual intimate image of another person, or anyone threatening to record or share an intimate image without consent of the subject.

Importantly, it must be proven the person creating and/or sharing the image knew the creation and dissemination of intimate images was non-consensual. NSW courts also have the power to order offenders to remove material from online platforms (or “to take reasonable steps to recover, delete or destroy images taken or distributed without consent”) with a penalty of two years imprisonment and/or a $5500 fine for non-compliance.

The images referred to also include manipulated – or deepfake – images, where genitalia or the performance of acts is depicted artificially. This is more broadly referred to as laws relating to “revenge porn”, since it is often ex-partners who create and distribute this material after the end of a relationship.

Potential avenues for legislation and extralegal solutions

In 2022, UNSW Law graduate Stephanie Tong, who presently works as a software engineer in legal technology, wrote a feature on the sexually abusive nature of pornographic deepfakes and the legal protections available to victims. Tong will be admitted to the Supreme Court of NSW next month.

She spoke to LSJ about the ongoing dilemma of dealing with deepfakes.

“A lot has changed since I conducted my study in 2022, even in this short period,” she said.

“The Taylor Swift deepfakes were available on X for 19 hours, were viewed 27 million times with 260,000 likes before the account that posted the deepfakes was suspended. It is important to note that this is far from the first incident.

“[Teenage actress] Xochitl Gomez and her team tried to remove pornographic deepfakes of her earlier this year also, but she was unsuccessful in having those images removed. So, despite X saying that it actively removes such material, this isn’t the case.”

Tong adds: “companies like X and TikTok should take active steps to identify and remove this material in a much responsive manner.”

“I talked quite little about deepfake detection in my paper, but recent studies have demonstrated that the accuracy of deepfake detection frameworks can be quite low, which means manual detection is necessary, which may not be sustainable due to the cost and capacity of the workforce required.”

Top image: Natacha Pisarenko/AP