Rohan Browning made his Olympic debut last night on the 100m track in Tokyo, clocking a 10.01 - the second-fastest time an Australian has ever run. If he qualifies for the Olympic final, it will be the first time an Australian has run the 100m final since 1956. However, the sprinter and Sydney law student reveals that his forthcoming constitutional law exam is keeping him grounded.

Hurtling down a 100m track in 10.05 seconds takes a lot of talent, precision and hard work. Every aspect of every day is considered and deliberate, designed to maximise the chance of shaving off another 0.01 seconds – or, if you get it just right, another 0.02 or 0.03. When 23-year-old law student Rohan Browning set this sizzling time at the Queensland Track Classic athletics meet in March, however, he says it was a blur.

“It’s funny, it’s all very automated,” he tells LSJ. “The best races are the ones when I can’t remember a thing. The worst races, I can walk you through it step-by-step afterwards. It clearly means I was trying too hard and thinking too much. Sprinting is really about the maximum exertion of power in the most relaxed way possible, so it’s really about preparation. You want to avoid errors and just let it happen.”

The race cemented his title as fastest man in the country and secured his spot at the 2021 Olympics, making him the first Australian to qualify for the men’s 100m in 17 years. He knows there’s more where that came from. Back in January, he broke the notorious 10-second barrier with a blistering (albeit wind-assisted) time of 9.96. On the home front, Patrick Johnson’s record run of 9.93 in 1993 provides constant motivation. Breaking it would certainly thrust Browning into medal contention in Japan.

The challenge sustains him through about 30 hours of training a week, split between track runs, gym sessions, Pilates, physio, saunas, and the dreaded ice baths that form a crucial part of recovery.

“It all adds up,” he says. “In professional sport, especially in this event, fractions of a second matter. The most infinitesimal margins are important. It becomes a full-time job – what you eat, how many hours you’re on your feet, how much you sleep, everything. You really do commit years to improving by 0.1.”

Browning is speaking to LSJ from a training camp in Northern Queensland, where he narrowly escaped the Sydney lockdown that could have dashed his chances. He was planning to go to Mackay anyway, but the outbreak of the Delta strain meant he and his coach dropped everything and went straight to the airport. Somewhere in the middle of it all, he sat a three-hour administrative law exam – worth 70 per cent of his grade – at a budget airport hotel in Brisbane, writing straight through his check-out time.

“Obviously it was a far from optimal situation,” he laughs. “One of the best things I’ve learnt from sport, that I hope will one day transfer to the law, is the ability to adapt and not get flustered under pressure.”

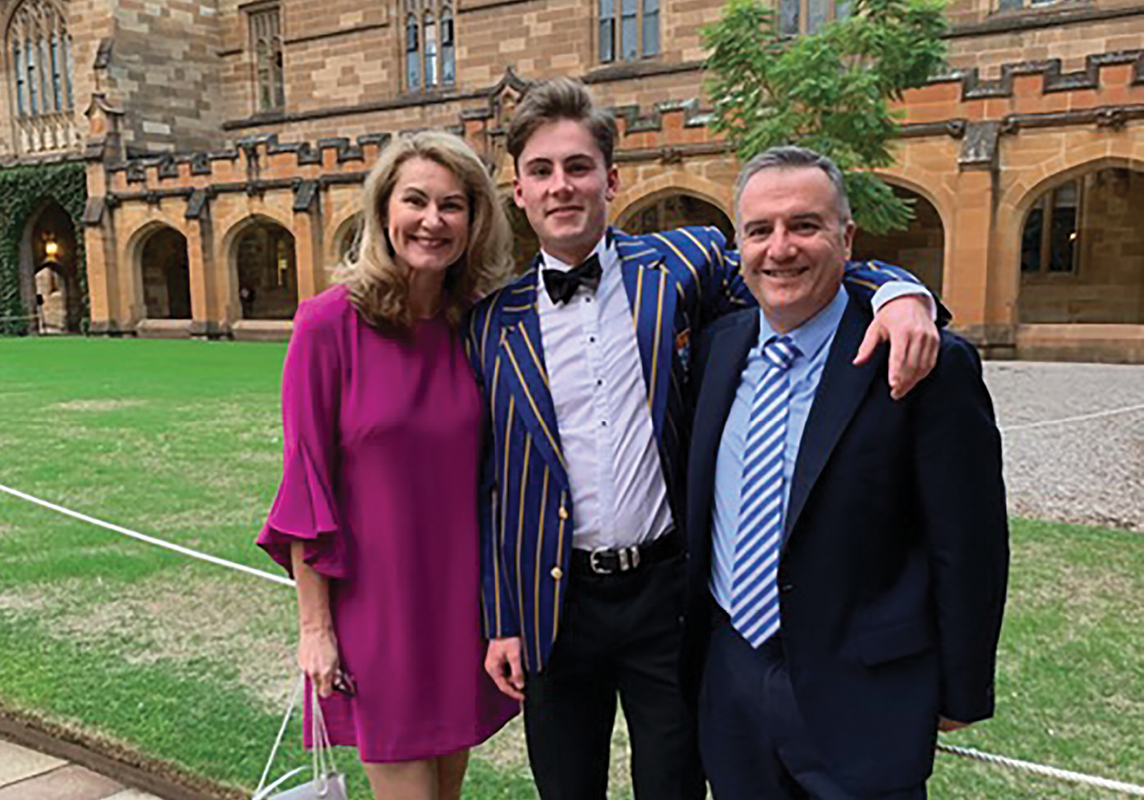

A talented high school debater, law was the obvious next step. He enrolled at the University of Sydney and spent a few years living on campus, but he says studying remotely is suiting him well as he juggles training commitments and competitions. He’s got about 10 units remaining, which he estimates will see him through until the end of 2022. And while he’s looking forward to completing clerkships – he’s interested in working in litigation or mergers and acquisitions – for now he admits sport is in the driver’s seat. There’s a beaten path for law students, but he knows the road less travelled will make him stand out.

“I’m drawn to the sporting aspect of the law,” he says. “Long-term, I think I’d like to become a barrister. I’m drawn to the gamesmanship and competition of litigation and I’m a very pedantic sort of person. If I look ahead to the transition from professional sport, that’s what really excites me.”

Coronavirus is casting a looming shadow over the upcoming Games. It’s Browning’s first Olympics, but he’s competed at the Commonwealth Games before, and he says the social side is huge. There’s a communal dining hall with cuisines from all over the world, open 24/7, as well as a festival atmosphere that he says feels like a real celebration of sport and humanity. The contrast will be brutal.

“If you get COVID, or you mix with someone who has, you’ll be frog-marched out of there and unable to compete at all,” he says. “The people who do well in this Olympics will be the ones happy to sit in their rooms and be content in their own company, because you won’t be able to go out and mix with anyone.”

Immediately after the Games, he’ll return to Australia and face a two-week hotel quarantine. It means no commiserating, if things go poorly, and no celebrating if things go well. Fortunately, he has a secret weapon that will help him through weeks of isolation: a three-hour constitutional law exam will be waiting for him when he gets home. He laughs. “That could be the trick up my sleeve.”