Possibly no nation in the world operates with greater secrecy than North Korea. Two defectors shine light on the dark state of affairs in their country.

Satellite images taken from space of North Korea at night show a country swathed in darkness.

The black space signifies a nation cut off from the world as a result of international trading sanctions, tenaciously guarded borders, and the threat of nuclear war. The northern side of the Korean peninsula has – both literally and figuratively – been left in the dark since the Korean War Armistice in 1953.

The darkness can be blamed on electricity shortages plaguing an isolated nation lacking the wealth or industry to light its cities. This is blindingly apparent next to the sea of electric splashes coming from South Korea, the seventh most prosperous economy in the world with a gross domestic product (GDP) estimated at US$1.4 trillion by the International Monetary Fund. North Korea’s GDP is closer to US$40 billion, with a per-capita GDP lagging behind developing countries like Myanmar and Bangladesh.

But the darkness also hides an array of human rights abuses occurring under the noses of the international community.

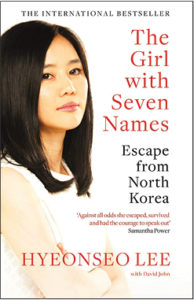

North Korean defector, author and peace activist Hyeonseo Lee shines light on some of these abuses in her bestselling biography The Girl With Seven Names. Her book, which she has also presented as a TED talk viewed more than 13 million times online, paints a harrowing picture of fear, indoctrination, bribery, propaganda, starvation and disappearances of North Korean citizens under the communist regime.

Lee witnessed the first of many public executions when she was just seven years old. When she was 14, her stepfather was accused of treachery and tortured to within inches of his life by the bowibu – the secret police and agents of Kim Il-sung (then Supreme Leader of North Korea and the grandfather of current Leader Kim Jong-un). When Lee’s stepfather was finally released to hospital, he took his own life.

“Very little do international citizens know about ordinary people surviving in North Korea,” Lee tells me during a private interview in Seoul, where she has lived as a political refugee since 2008.

She explains how the plight of North Koreans, who she refers to as the “forgotten people”, is overshadowed in world news by military displays of force, nuclear weapons tests, or photos of Kim Jong-un riding white horses through snow. Or, in 2019, the unprecedented meeting between Kim Jong-un and US President Donald Trump at the demilitarized zone (DMZ).

“It’s like the allegory of a cave,” Lee continues. “The North Korean people have no power to deliver messages to the world. They have no voice. The world only knows what their dictator tells us – about political and military issues.”

Life in the dark

North Korea was known as the “hermit Kingdom” even before the Japanese occupation that preceded the Korean War. It developed as an ancient and obscure culture whose people kept to themselves. But this secretive nation’s retreat into its shell has been propelled by the totalitarian rule of the “Kim” regime (the succession dictators Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-il and Kim Jong-un) since it was artificially cleaved in two during the Korean War. Only recently have defectors such as Lee begun to shine a light on the darkness north of the border.

Lee’s cave allegory is apt. North Koreans have no access to the internet. Four state-owned television stations broadcast “news” promoting the communist regime’s ideologies. Twelve newspapers and 20 major periodicals are all published in the capital of Pyongyang by trusted officials in Kim Jong-un’s Workers’ Party. This state media managed to convince Lee that her childhood in “the greatest nation on earth” was blessed, while citizens in South Korea and America (“yankee bastards”) were suffering and deprived. This was even as she witnessed whole families starving to death in the streets during the 1990s.

Her book also explains the black space representing North Korea on satellite images: blackouts occurred most nights, and electricity was a rare luxury.

Today in Seoul, Lee has addressed hundreds of lawyers at the 2019 International Bar Association (IBA) Conference about the dearth of human rights or legal protections in her birth nation. Her opening sentence speaks volumes.

“This is more lawyers than I have ever seen!” she exclaims to the auditorium. “Before I left North Korea I had never heard of a lawyer – I didn’t even know they existed.”

Even after 10 years and seven name changes to escape the North Korean regime, Lee is covert about the interview she has granted me following her speech. Security guards wave metal detectors over me, then guard the door as we chat in a private meeting room with no windows. The Kim regime has openly denounced Lee as an enemy of the state and speaking with a journalist for a legal magazine in a free country like Australia is a risk, even in South Korea.

When I ask Lee what human rights are being violated in North Korea, she responds in a hiss. It’s as if Kim Jong-un himself could be listening.

“Everything!” she whispers. “In North Korea you are deprived of freedom of speech, religion, food, movement, water, everything. Even breathing the air is considered a gift from the Supreme Leader.

“In the north, people have no concept of human rights. People are so scared of having any opinion, and there is no access to information from the outside world, so people don’t know they are oppressed. They can’t even know that their human rights are being violated – because they don’t know what human rights are.”

What little we know

Between 2013 and 2014, the UN Human Rights Council led a commission of inquiry into human rights violations in North Korea. North Korea refused to participate in the hearings, but 80 defectors, refugees, and abductees publicly testified to the committee. A further 240 witnesses gave evidence via confidential interviews to protect them and their families from retaliation by the Kim regime. The resulting Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea declared evidence of “systematic, widespread and grave human rights violations”, as well as “a disturbing array of crimes against humanity”.

Former Australian High Court judge Michael Kirby chaired the inquiry and presented its findings to the UN Human Rights Council in 2014. He likened the horrors of the North Korean regime to the atrocities of the Nazis, apartheid and the Khmer Rouge.

“Extermination, murder, enslavement, torture, imprisonment, rape, forced abortions and other sexual violence … The gravity, scale, duration and nature of the unspeakable atrocities committed in the country reveal a totalitarian state that does not have any parallel in the contemporary world,” Kirby told the Human Rights Council.

During daylight hours, Google Earth shows what appear to be prison camps, in the same location and as described by North Koreans who testified to the UN. The Korea Institute for National Unification has estimated that there are between 80,000 and 120,000 people imprisoned in those camps.

Judge Thomas Buergenthal, a survivor of Auschwitz who served on the bench of the International Court of Justice and in 2017 sat on the bench of an IBA inquiry into North Korea, concluded that the conditions of those prison camps are “as terrible, or even worse” than the Nazi concentration camps he experienced during the Holocaust.

North Korea has denied their existence and rejected the findings of the UN commission of inquiry. It has also refused to allow amnesty groups and UN officials inside its borders to disprove them.

Escaping a lawless state

One of North Korea’s most high- profile defectors, former deputy ambassador to the United Kingdom Thae Yong-Ho, describes the dubious legal process North Korean citizens are afforded before being sent to prison camps.

“If, by accident, you kill someone by car, you would be brought to trial and have an opportunity to defend yourself,” explains Thae. “But if you do or say something – anything – against the system and the Leader … For example, if you were drunk and told your friend, ‘Kim Jong is a son of a bitch!’, the secret police might find out. Then there would be no trial. You would be arrested and sent to the prison camps.”

Thae is the highest-ranking North Korean diplomat to defect. He has granted me an interview at great risk to himself, his wife and two sons, who all made their daring escape to the South Korean embassy while he was posted in London in 2016.

A team of bodyguards pat me down and check my bag to ensure I carry only the agreed-upon notepad, pen and iPhone. They eventually wave me inside the interview room, where a man in a low-brimmed hat, long coat and dark glasses begins to dismantle his disguise. It is Thae.

“In South Korea there are many North Korean spies and agents,” he says. “I’m number one on the North Korean assassination list. My family and children are protected by bodyguards 24 hours a day. Whenever I travel, I wear a cap and sunglasses. I like living in the free world, but I am not totally free at all.”

Thae is certain he would be killed if he returned to North Korea while the Kim regime rules. He explains that travel to the country, even by non-partisan tourists, is highly dangerous. The most recent example of this occurred when Australian student Alex Sigley, who had been organising state-sanctioned tourism to North Korea under his company Tongil Tours, was arrested and vanished suddenly in June 2019. Sigley was released one month later and returned to Australia but has refused to answer any questions about his arrest.

US student Otto Warmbier, who visited in 2016, was not so lucky. The 21 year old was arrested and held hostage for 18 months. When North Korea eventually released him, he was flown home in a coma with unexplained brain damage. He died without regaining consciousness.

“I still have a lot of nightmares about what has happened to my sister and my brother, even my friends, back in North Korea after my defection,” Thae says. “My ambassador, he used to be my good friend. He was called back to Pyongyang and he just vanished. Like steam in the air.”

If a regime headquartered in Pyongyang – just 200 kilometres north of where we are speaking in Seoul – wields such power, why would Thae put himself at risk by publicly denouncing it to a magazine read by Australian lawyers?

“I want to ask the world community of lawyers to do something to improve the situation of North Korea,” he says.

“Every year in December in Geneva, the United Nations adopts the resolution on North Korean human rights. I think if the world continues to do it again and again and again, the legal community of the world can let the North Korean people know that the world is trying, that they are not neglected.”

An end in sight?

Many North Koreans believed that the death of the first Leader Kim Il-sung in 1994 would lead to the communist regime’s collapse. But when he died of a heart attack aged 82, his son Kim Jong-il took over and the regime continued.

When Kim Jong-il passed away in 2011, his son Kim Jong-un succeeded him. It’s why Thae ultimately decided to defect – to free his family from the tyranny that could go on for decades.

“As a father, I thought it would be a crime to force my children to go back to Pyongyang. I decided I should cut off the slavery at my point,” Thae explains.

Both Thae and Lee say it is difficult to imagine an end to the totalitarian regime, when current generations have never seen or experienced an alternative. They believe the Kim dynasty will ultimately be toppled by a lack of money and resources, but neither can put a timeframe on that demise.

“Last year, countries were all talking about putting pressure on North Korea and I hoped that the regime would collapse,” Lee says, indicating the new sanctions that US President Trump and South Korean President Moon Jae-in imposed on North Korea in 2018.

“But right now, it seems like we are giving more power to the North Korean dictator, so I am unsure. The summit that President Trump and Kim Jong-un held seemed to legitimise his system. I really hated seeing that.”

Many human rights groups oppose economic sanctions, warning that they cause suffering and starvation for North Korean people. But Lee believes the sanctions can force a decline in state income, and will be a key factor in the demise of the totalitarian system. Besides, she says, most North Korean people have already stopped relying on government jobs and rations. Her book describes how ordinary citizens have developed creative ways to smuggle and trade goods on the black market via corrupt officials. It’s one of the biggest ironies in the communist state: American dollars have become the most valuable commodity.

Both Lee and Thae long for a future in which they can return to their hometowns and be reunited with friends and family. Until then, Lee has an emotional message for the North Korean people.

“I don’t know when we can be united or when I can meet them again, the North Korean people. All I can hope is they are not dying,” she says.

“There is not any message of strength or bravery that I want to send. Other than to stay alive. Just stay alive. In North Korea, there is nothing more important.”