As we celebrate 800 years of Magna Carta, it's timely to reflect on the bloodshed and tyranny behind its creation and the reasons for its powerful and enduring legacy.

Since the 13th century, Magna Carta has been looked to symbolically for guarantees of royal conduct and the regulation of power between governors and the governed. It has been respected and referenced whenever individual freedoms have been threatened or needed to be asserted.

It has been regarded as akin to legislation, and the fact there are so many versions and interpretations of the document creates a certain mystique.

However, it is not so much reference to the words of any particular chapter that is important. The whole document is symbolic of the continuation of the “good old laws” of England – even unwritten laws – and of the subjection of all, even monarchs, to those laws.

Magna Carta’s importance lies less in its text and more in the principles that underlie it – and the symbolic way in which it has been invoked for 800 years in many countries and circumstances.

From the late 13th and early 14th centuries, Magna Carta became regarded as the pre-eminent statute of the realm. It was given pride of place in publications of statutes and other legal texts. It was lavishly illuminated in the fashion of the times. It played an important part in legal education, including as a source of moot questions in legal training. It was publicly proclaimed from time to time and copies displayed. It was cited in political debate, litigation and as authority for legal remedies from the monarch by petition or otherwise.

A crucial aspect of the rule of law is affirmed by the charter: that justice will be done by following rules that have been stated in advance and are knowable by all and fair.

From the 16th to the 18th centuries, Magna Carta was invoked in battles between monarchs and parliaments over the nature of law, in defining the prerogatives of sovereignty and individual property, through to conflicts between the people and anyone who claimed power.

In 1628, Sir Edward Coke in his Institutes of the Laws of England included a complete commentary on Magna Carta. It was closely studied and quoted in constitutional struggles in the 17th and 18th centuries when it was invoked to legitimise protest and resistance to invasions of personal liberty.

It was a foundation for the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the English Bill of Rights of 1689 and the Act of Settlement of 1701. It inspired the American independence movement in 1776 and the American Constitution (“no taxation without representation”).

In 1948 Eleanor Roosevelt, the champion of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, told the United Nations: “We stand today at the threshold of a great event in the life of the United Nations and in the life of mankind. This declaration may well become the international Magna Carta for all men everywhere.”

The origins of Magna Carta

Throughout its long history, Magna Carta has acquired a significance the originators could never have foreseen. And while most people think they know the origins of Magna Carta, the real story is much more interesting.

A view commonly held (but incomplete) is that King John made an agreement with the barons in 1215 at Runnymede. This agreement became “law” and created rights, and it has been applied ever since as the source of good in public administration, democracy, separation of powers, the rule of law, independence of the judiciary, trial by jury, equality before the law and more.

In the early history of England, kings held sway. There was competition between kings, nobles, their subjects, and the Christian Church of Rome. Over time, laws developed to regulate these matters, but they were not, until at least 594, written and recorded laws.They survived thanks to memory and retelling. Laws began as dispute resolution mechanisms among the people and were appropriated by kings claiming to be acting in the interests of peace.

There were not police or legal professionals working in criminal justice and violence was prevented and suppressed through the infliction of even greater violence. Every community and its lord needed a basic understanding of the law, as did the king.

There was a communal and largely unwritten understanding of what was or was not lawful. At the time of the 594 code of Aethelbert, King of Kent, the written versions of laws claimed not to make new laws but to define customs and practices already in place.

The Norman Conquest in 1066 embedded the pre-existing “English” laws that William acknowledged, but tension was created between the force of conquest and obedience to the old law. From about 1100, English law was again operating routinely. The Domesday Book from the survey of 1086 shows the survival of Anglo-Saxon laws. The Coronation Charter of King Henry I of 1100 and his laws of 1115, and the so-called laws of Edward the Confessor, compiled in about 1140, were significant in the later drawing of the document sealed in 1215.

Life before Magna Carta

King John was a Plantagenet, an ancient line from Angers on the Loire with a history of conquest and plunder, connected to the English throne by the marriage of his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine. When Henry I died, Stephen reigned. His heir died and, after some dealings involving Empress Matilda, he recognised Henry II as king. In 1154, he inherited a system of law from his grandfather, Henry I, which he set about changing while quarrelling with Thomas Becket. Becket’s murder in 1170 did not play well for Henry II or his line and it aided in the revitalising of the Coronation Charter of Henry I. Becket had called for the “liberties” (or privileges) of the English church, which inspired others to seek to have their liberties enforced against a tyrannical king. For the time, however, the king held sway.

From the Assize of Clarendon in 1166, while Becket was in exile, Henry II set about reforming the criminal law. He provided for juries to report suspected robbers or murderers who would be detained by sheriffs for trial before local law officers. Prisons were built, exile and outlawry were decreed for notorious criminals, and other laws were enacted that created a flood of litigation. Henry II had to employ additional judges and officials to deal with it. By the 1170s, there were professional courts centred on Westminster but travelling periodically on circuit. Knights and local landowners were drawn into law enforcement. But before long, inequities appeared and resentment was strong.

A crucial aspect of Magna Carta is that justice will be done by following rules that have been stated in advance and are

knowable by all and fair. It is a shield against tyranny and abuse of power.NICHOLAS COWDERY, AM QC

In 1173, rebellion broke out and was put down the following year. The king then tackled more strongly the powers of local lords and assumed greater control over the administration of both criminal and civil justice. A significant segment of the population viewed Henry II as a tyrant.

One chronicler, Ralph Niger, claimed that Henry II deliberately delayed judgments so justice could be bought and sold. He promoted serfs and soldiers as officials. He debased monasteries and debauched the wives and daughters of barons. He overruled the old laws, set aside “liberties”, legislated scandalously for royal dominion in the forests, supported the usury of the Jews, ordained barbaric punishments and so on. All this served to increase the power of the king – and these failings heralded some of the clauses of Magna Carta.

If Henry II was a tyrant, he was nonetheless effective in government. England expanded and prospered. By contrast, his youngest son, John, was a tyrant with no redeeming qualities. He was cruel and contemptuous and came after his elder brother, Richard – who died without heir – had bled the country for his own gain. John was crowned in May 1199 and, over the next five years, piled catastrophe upon catastrophe at a personal and national level, including losing most of his territory in France. He routinely abused the law and his subjects but, because the law was regarded as being there primarily to serve the monarch, little could be done.

After losing Normandy in 1204, King John was obliged to stay in England among the barons, where propinquity bred contempt. From 1205 he challenged the church, seeking to have his own candidate elected Archbishop of Canterbury. He lost that contest and Stephen Langton, a staunch Becket supporter, was consecrated by the pope in 1207 but was obliged to live in France. King John refused to recognise him and in 1212 Pope Innocent III excommunicated England and the royal court.

From 1208 to 1214, the services of the English Church were suspended and the populace adversely affected in various ways. John retaliated by expropriating what he could from the church and bled the barons to build a war chest to retake his French territories. The pope was rumoured to be plotting to depose King John and put a Frenchman on the throne. Some barons were discovered plotting John’s death and fled to France. A powerful group, English and French, baronial and ecclesiastical, grew around Stephen Langton in exile in France in 1213 where the Coronation Charter of Henry I (from 1100) was invoked. A French invasion loomed.

King John, having none of the diplomatic talents of his father, capitulated in 1213. To gain protection from France, he surrendered England and Ireland to the pope, promising a perpetual annual rent the equivalent of one million pounds in today’s money. In 1214, he attempted to re-establish a foothold in northern France but was defeated. The English churchmen feared papal interference in their English church. Langton returned to England and preached against King John’s moves and seizures of church properties – and became pivotal to the development of Magna Carta.

Late in 1214, the circulation of Henry I’s Coronation Charter led to King John’s issuing a charter of liberties for the English Church, but it was not enough. Barons and churchmen were meeting at various places and a group of barons known as the “northerners” emerged. It was this political movement that forced King John to Runnymede. The alternative was deposition or death.

The birth of Magna Carta

Documents began to be prepared from late 1214 through to June 1215, including the so-called Unknown Charter, probably dating from the spring of 1215. Various drafts of clauses survived and were later distributed in various places, sometimes with provisions that differed from the sealed Charter. King John, seeing the writing on the wall, granted new privileges to bishops and barons, abolished large tracts of royal forest, granted privileges and made concessions to barons and opponents about the arbitration of disputes. But it was too little, too late. On 5 May 1215, the malcontents gathered at Brackley in Northamptonshire and publicly repudiated their oaths of allegiance to the king. On 17 May, a group seized London and Westminster on behalf of the rebel barons. Negotiations continued as both sides tried to preserve the peace. Langton was concerned to ensure the English church was properly considered.

A place had to be selected for the agreement to be sealed. Runnymede (unnamed until then) was at an appropriate distance from both the rebel stronghold of London and the King’s castle at Windsor. Agreement was reached on 15 June 1215. The document was first called the Charter of Liberties. (The title “Magna Carta” came in 1217 to distinguish its reissue from the smaller Forest Charter of that year.)

Liberties were then understood a little differently from today. The word “liberty” was coined by the Greeks, meaning immunity from taxation. The Romans used it to mean negation of slavery. The Anglo-Saxons used it in the sense of “privilege”, denoting freedom from dominion by royalty. This was well short of the catalogue of rights and freedoms in international and domestic instruments that we now understand as liberties.

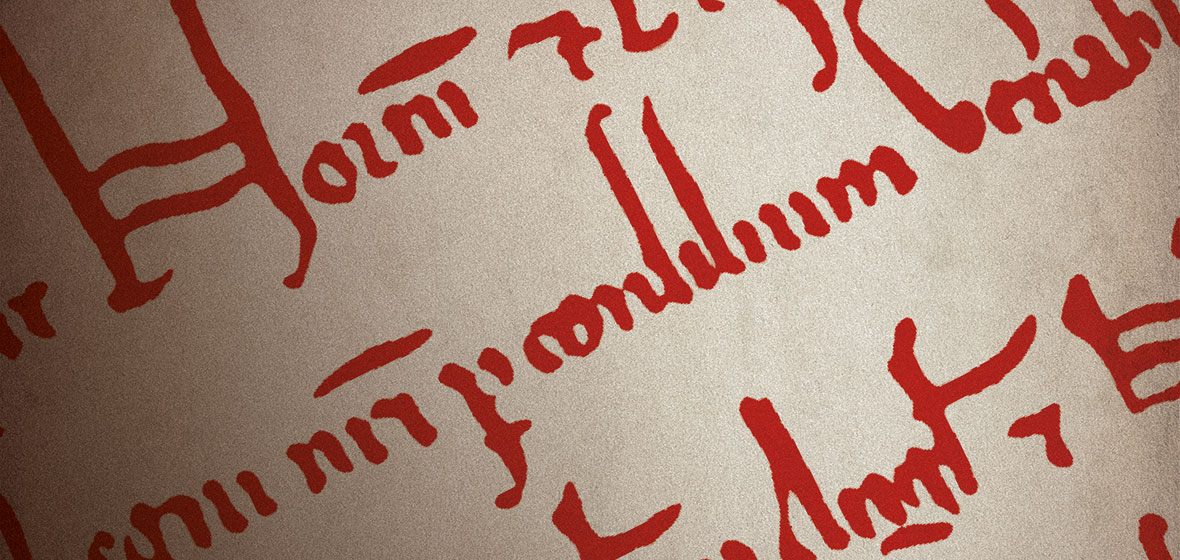

Much of the Charter of Liberties reflects the Coronation Charter of Henry I of 1100 and the Laws of Edward the Confessor. Some of it reflects more international influences from Europe. Some of it was inspired by Stephen Langton. The original Charter of Liberties was handwritten in mediaeval Latin on untanned animal skin (vellum).

It was more than 3,500 words and what later became 63 chapters. The first and most important chapter granted liberties to the church, not the barons. “Free men” – up to 40 per cent of the population of England of between two and four million people at that time – had their liberties declared in subsequent clauses and all “the men” of the realm were mentioned later.

On 19 June 1215, four days after the sealing, the rebels paid homage to the king and he declared an end to hostilities. Two uneasy months followed while all sides waited for the contract to be honoured. Copies of the Charter were made throughout July and sent out to be read aloud in more than 30 county courts, probably in Latin and French and possibly in English.

Sealed copies were still being copied and dispatched by 22 July. There are four surviving originals of the document of 15 June 1215, but the copy bearing the King’s seal has been lost. (They were brought together in the British Library and House of Lords in February this year.)

Not all went to plan, however. The barons refused to surrender London. The king refused to dismiss his constables. Langton was suspended and went into exile. The king sent envoys to Rome with a copy of the Charter, but the pope had learned of it and was already taking action. He annulled the Charter on 24 August 1215, the letter arriving in England near the end of September by which time the Charter of Liberties was already dead (at the latest probably from 5 September when other documents were proclaimed at Dover on behalf of King John). It thus survived in its first life for about nine weeks.

From 17 September 1215, the king issued many instructions for the seizure of rebel lands. Civil war began and the rebels sought help from the Scots, the Welsh and the French (whom they invited to invade, and they did).

While campaigning in Lincolnshire in October 1216, King John fell ill and died (it is said from dysentery after eating a surfeit of peaches). The Crown passed to his eldest son, Henry (then nine years old), and the coronation occurred at Gloucester Abbey on 28 October 1216 – Westminster still being in the hands of the rebels.

On 12 November 1216 at Bristol, the Charter of Liberties was reissued as affirmation of the new king’s future good government. It was sponsored by a papal legate, so acquired explicit papal approval. But the text had been significantly modified from that of 15 June 1215. The war continued, the French were forced out and the rebels sued for peace.

In November 1217, the Charter of Liberties was again reissued, with still further modifications to the text. In 1216 and 1217, the clauses that most directly challenged royal sovereignty were removed.

Key dates

- 1215 sealing of the Magna Carta

- 1679 passing of the Habeas Corpus Act

- 1948 The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- 2015 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta

Also in 1217, Henry III issued a distinct charter, the Forest Charter, regulating and restricting royal administration of those parts of the country under forest law. The Charter of Liberties became known as Magna Carta to distinguish it from the smaller Forest Charter. (The idea that “Magna Carta” was intended to reflect its significance was a later invention.)

In 1225 Henry III confirmed both Magna Carta and the Forest Charter. This version of Magna Carta differed again and became the standard, as reproduced (more or less) in subsequent reissues. It was down from 63 chapters to just 37.

There were further reissues of Magna Carta over the next 70 years. In 1253, the document is known to have been read aloud throughout the land in English, as well as Latin and French. In 1265, the 1225 Charter was reissued.

The last two issues in 1297 and 1300 were intended to achieve support for King Edward I in high spending on warfare that was unpopular with barons and the population generally. The 1297 document was the first to be copied onto the official “Statute Roll” and its 37 clauses thereby became the text that is definitive under English law and most often quoted.

The power of Magna Carta

The main contemporary strength of Magna Carta is as a foundation of what is described as the rule of law. It is said to show that no person is above the law and the process whereby agreement was reached is said to reinforce that the people should not only be governed by the law, but be willing to be so. That is likely only if those in power are also subject to the law.

The notion of the rule of law may conveniently be described in the words of the Secretary-General of the United Nations in 2004: “For the United Nations, the rule of law refers to a principle of governance in which all persons, institutions and entities, public and private, including the State itself, are accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced and independently adjudicated, and which are consistent with international human rights norms and standards. It requires, as well, measures to ensure adherence to the principles of supremacy of law, equality before the law, accountability to the law, fairness in the application of the law, separation of powers, participation in decision-making, legal certainty, avoidance of arbitrariness and procedural and legal transparency.”

Magna Carta has provided inspiration and support for progressive development in governance worldwide since the Middle Ages. It stands for the continuation of basic law – a framework for order and peace fashioned by and from the people upon which contemporary laws are made and which is innate and inalienable.

It stands for the triumph of liberties over tyranny, and that justice will be done according to certain laws that are knowable in advance. It stands for the value of democratic processes in the government of the people, the value of the separation of powers, independence and professional competence of the judiciary, equality before the law and due process, including the presumption of innocence and burden of proof on the prosecution, trial by a jury of one’s peers (as it later developed), “no taxation without representation”, freedom from arbitrary punishment and proportionality in sentencing.

It is said to have been the origin of the law of trusts and an early example of the protection of women’s rights, in widows not being forced to remarry and being entitled to their inheritance. It also dealt with a multitude of local and temporal regulations that are of less enduring significance but which secured common freedoms for that time. Magna Carta, as it has come to be understood and called upon for 800 years, operates as a shield against tyranny, abuse of power and oppression of the governed.

It has become the talisman of a society in which tolerance and democracy reside.