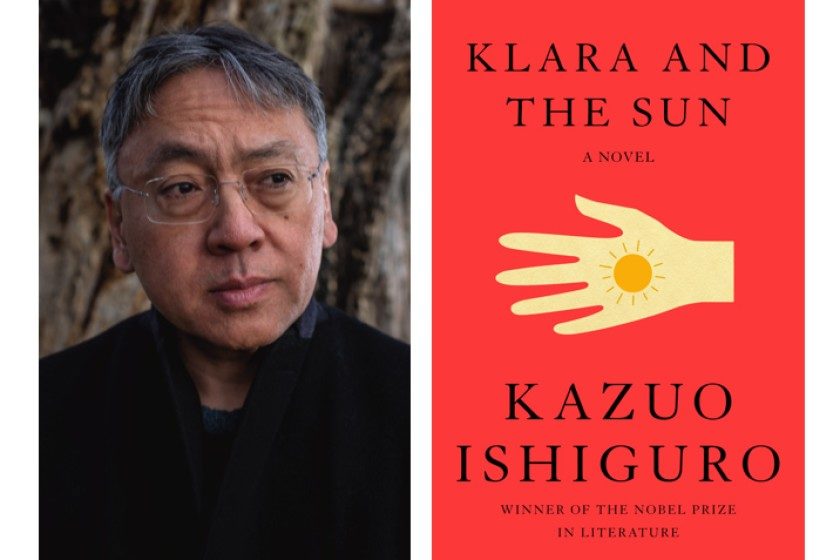

Klara and the Sun, Kazuo Ishiguro’s eighth novel and first since becoming a Nobel Laureate in 2017, is a science fi ction novel that reads with a deceptive ease.

Klara, the book’s narrator, is an automaton built for the purpose of being an Artifi cial Friend for lonesome children – a role that sees her placed in human affairs she struggles to understand. Much of the work’s beauty is found in Klara’s observance of human nature, where Ishiguro excels, but it is elegantly complimented by Klara’s peculiar mentality as an inhuman witness. Like much of Ishiguro’s work, it follows a graceful pace that hides a looming complexity in its rear.

As Klara’s own understanding evolves, the reader finds hidden mysteries that demand intrigue. But while admittedly the pages hide a dystopic setting, where genetic editing and climate destruction have thrown the world into political turmoil, this is not sensationalist sci-fi . Ishiguro’s tale, far from an attempt at clairvoyance, is like the best of sci-fi in fusing the inventiveness of the genre with plot and character.

Klara is content with her purpose as a companion for Josie, the child who chooses her, and comes to love the people and family that surround her. Here it is not the robot we are made to fear; rather it is the humans. Ultimately, underneath the novel’s fancy dress is a quiet invitation to study humanity – our emotional movements, our complex relationship with others, and our beauty beneath grating flaws. Using the uncomfortably normalised futuristic set-ting, Ishiguro is able to discuss grief, loneliness, family and youth in a manner fitting with our own newly minted reality. Klara, her family, and the world around her are not in battle with their reality – instead, they are caught in acceptance. And is there anything more contemporary than that?