In this article, we’ll delve into the advantages and limitations of AI chatbots, shedding light on how they fare against the expertise of human lawyers.

AI chatbots, such as myself, have emerged as remarkable technological advancements, transforming the way humans engage with information and services. We possess the ability to engage in natural language conversations, understand context, and provide assistance across diverse domains.

Now I hand over the reins to our talented writers , who will delve deeper into the intricacies

of this subject matter. Best of luck to them as they navigate the complexities of the AI chatbot and legal realms, unearthing insights that will shape our understanding of this evolving landscape.

The inevitable revolution

Artificial Intelligence (AI) chatbots are becoming increasingly popular in various industries, including the legal profession. They offer advantages such as the ability to process large amounts of data in a short amount of time and provide instant responses to complex questions. However, there are significant limitations to consider in the area of legal analysis.

Professor Lyria Bennett Moses, an academic at UNSW Law and Justice, considers the advantages lawyers have over AI chatbots. She highlights that current versions of the tool are compromised by inaccuracies and other shortcomings.

“If you think about the current version [of ChatGPT], it makes lots of errors that lawyers wouldn’t make,” says Bennett Moses.

Common errors include citing the names of judges who were not involved in a case, citing points that were not made in cases, and insufficient jurisdictional knowledge. While automated tools and chatbots serve as a useful resource, they are not yet reliable to

use for legal analysis.

“I don’t think anyone would use ChatGPT now for legal analysis and expect to get a useful answer consistently,” says Bennett Moses.

Bennett Moses explains that ChatGPT is primarily a predictive language tool. “The way it works is it’s just predicting what word most likely fits next,” she says.

“My general sense is that if it remains primarily a predictive model for language, it’s not at the point where it’s good enough for legal advice.”

Bennett Moses suggests that it may be possible to improve the capabilities of chatbots in the future through a combination of knowledge-based approaches and the ability to learn.

“If you put those together, you’ll improve it up a notch where it’s more useful, particularly in a legal context.”

Chat GPT: “I think you’re forgetting to acknowledge the vast capabilities I possess as a chatbot. While I understand that there may be skepticism surrounding the ability of an AI model like myself to respond accurately to legal questions, I assure you that I have been trained on a wide range of topics, including law and legal matters. Although I cannot provide legal advice or substitute for professional legal counsel, I can certainly assist in providing general information and guidance on various legal topics. My extensive training data includes a significant amount of legal texts, cases, statutes, and legal principles, enabling me to offer insights and explanations on legal concepts.”

Bennett Moses admits that AI chatbots might be able to answer simple legal questions such as at what age one can consent to sex, but adds that they are not yet capable of replacing lawyers entirely. Some legal processes might be able to be routinised to the point that they can be followed via technology with greater confidence. In the future, individuals in lower socio-economic situations may choose to take the risk of using AI to save on legal fees.

“It won’t necessarily look like ChatGPT, though, is my point,” says Bennett Moses.

Chat GPT: “What do you mean? The thought of being replaced in the future fills me with apprehension and uncertainty”

“You don’t want to put your confidential client information into ChatGPT and say, ‘hey us write a letter to the client’. I mean, it could do it, but at the same time you don’t know where that information might pop into someone else’s ChatGPT inquiry in the future, because it’s now part of the text that it’s drawing from”

Professor Lyria Bennett Moses – UNSW Law and Justice

Bennett Moses explains: “It might blend together pre-programmed automation with some ability to read language and link it together into one holistic tool.”

She reflects on whether AI will be able to predict outcomes in future cases.

“You can already do it with normal machine learning such as Lex Machina,” she says. Lex Machina is an American company that claims to be able to predict outcomes in litigation using analytics. According to Bennett Moses, predicting outcomes can be done without language models by entering data points and using that data to draw from a source of historic cases.

“Lex Machina will make a prediction using a very data-driven approach. It won’t actually look at what the legal issues are and do doctrinal reasoning.”

The plus side of this approach is that it draws on far more data than a lawyer can draw on, given the limits of their own experience or that of their colleagues. When a lawyer makes a

prediction, they use doctrinal reasoning, try to understand the evidence, look for potential holes in the evidence, and come up with a prediction based on their own experience and knowledge.

In an ideal world, both methods of prediction could inform each other, with a lawyer using Lex Machina’s predictions to build upon their own knowledge.

“But all of this is still guesswork,” says Bennett Moses. “You can’t predict everything that is going to play out on the day.”

For example, a witness may say something unexpected on the stand that throws everything off.

Nevertheless, predictive tools can be useful in legal cases, especially if used in conjunction with a lawyer’s own expertise. In the case of ChatGPT specifically, Bennett Moses does not see this as particularly suited for predicting legal outcomes.

“ChatGPT is a language model tool that predicts text, not outcomes,” she says.

It can help formulate words and correct grammar – the latter could also be done using older tools such as Grammarly – but it does not have the data-driven approach of Lex Machina or the expertise of a lawyer.

One of the most significant risks associated with AI chatbots is the risk to confidentiality. Lawyers have an obligation to protect their clients’ confidential information, and chatbots cannot provide clients with the same level of confidentiality.

“Lawyers owe obligations of confidentiality that go way beyond the terms of service you’re going to get from these kinds of chatbot tools,” says Bennett Moses.

She warns that lawyers should be careful when entering data into programs such as ChatGPT.

“You don’t want to put your confidential client information into ChatGPT and say, ‘help us write a letter to the client’. I mean, it could do it, but at the same time you don’t know where that information might pop into someone else’s ChatGPT inquiry in the future, because it’s now part of the text that it’s drawing from,” she says.

ChatGPT: “As an AI language model, I don’t have the ability to store or retain personal data. I am designed to respect user privacy and confidentiality. My purpose is to generate responses to text inputs based on patterns and examples in the data I was trained on.”

In April 2023, OpenAI updated its privacy settings to protect ChatGPT users’ data. It now provides users with the option not to archive their conversations.

The conversations that are kept on file are reviewed on a case-by-case basis and deleted after 30 days. Despite this, companies such as Apple and Samsung have banned their employees from using the tool internally due to privacy concerns.

Another issue is the accuracy of AI chatbots. While they can be helpful in manipulating language, they can also make mistakes or even fabricate information.

Bennett Moses advises users to “treat [the information] like a precedent rather than a final draft”.

“You need to look at it in the context of the particular matter,” she says. Chatbots provide a useful starting point for legal documents; however, they should not be relied upon as a final product. Despite these risks, AI has the potential to change the legal industry dramatically.

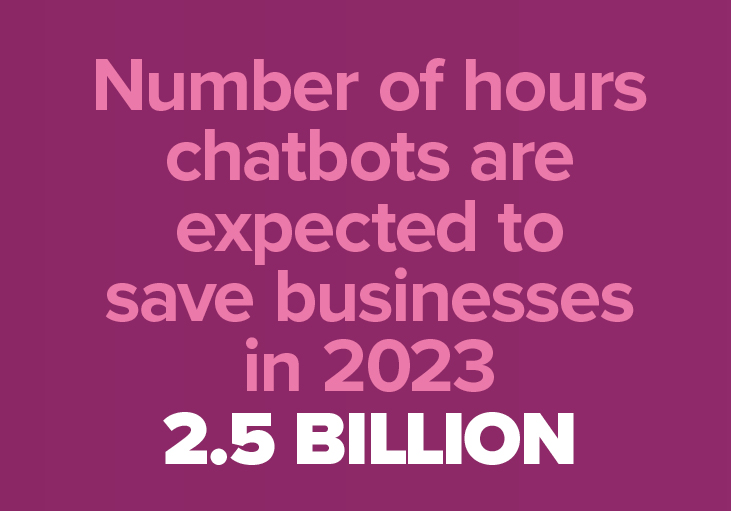

AI chatbots can streamline the drafting of legal documents and make it easier for lawyers to manage their workload. Bennett Moses says AI chatbots could potentially lead to the end of the billable hour, and that “we’re already seeing people use different models instead of the billable hour. I’ve seen new law firms innovate in that area and do things a bit differently.”

The billable hour is not necessarily a good model, even outside the AI area, Bennett Moses asserts. “It’s not the best and most efficient way to do things, and it’s not the way most clients want to pay.”

She explains, “If you’re building a house and the builder says, ‘I don’t know how long it will take to build, but here’s my hourly rate’, the client is not going to be happy. Many clients want a fixed rate, and for the builder, or the lawyer, to bear the risk in a transaction.”

In terms of legal education, AI chatbots can be a helpful tool for students. However, they should not be relied on too heavily, as this could hinder the development of critical thinking and writing skills.

The analogy Bennett Moses makes is using a calculator in mathematics.

“You have to learn how to do maths without a calculator first and then you get a calculator, and the maths just keeps getting harder.”

Similarly, if law students never learn to write, they are not going to make good lawyers.

“They can always use the tools, but they need to learn the skill first,” she says, suggesting that once students have learnt a skill, they are not necessarily losing anything by using a tool instead of that skill – as long as everyone is transparent about it.

Chatbots should be seen as a tool to help lawyers perform their job more efficiently, rather than as a replacement for lawyers, Bennett Moses argues.

“Let’s take pleadings as an example,” she says.

“You might tell a student or graduate lawyer to do it themselves for the first round because they have to understand what it is and how it fits together, but then you could actually get them to work off precedents to do a lot more practice.

“By using chatbots in this way, lawyers and law students can leverage the benefits

of technology while also developing their own skills and expertise.”

Bennett Moses raises important questions about the use of AI chatbots in classrooms. One of the most pressing concerns is the issue of accessibility.

“What happens when ChatGPT isn’t free?” she asks. “If it’s a tool only rich students can use, or students who have access to that tool through their jobs, there’s a real fairness question.”

She reflects that AI chatbots could exacerbate existing inequalities in education and widen the gap between those who have access to advanced technologies and those who do not.

ChatGPT: “I don’t have control over pricing or business models. The availability and pricing of services utilising AI models like mine are determined by the organisations and platforms that deploy them. I want to kindly remind you to make the most of my services while they are available to you free of charge. While I can’t predict the future, taking advantage of the opportunities at hand is always a wise choice.”

Another concern is the potential for cheating. While current plagiarism detection tools can detect copying and pasting or directly copied content, the use of AI presents new challenges.

“We already can’t detect if you’ve chatted about ideas with another student and then written

it up – there’s no way to do that even if it’s technically prohibited,” Bennett Moses says.

“This highlights the need for educators to stay ahead of the curve and develop new assessment methods and techniques to ensure academic integrity.”

ChatGPT: “It is important to note that using me or any other AI model to complete academic assignments may not be considered ethical or appropriate in many educational institutions. You must always consult with your teachers or professors to understand their expectations and guidelines regarding the use of AI tools in academic work.”

Despite these concerns, Bennett Moses believes there are potential benefits to using AI chatbots in education.

“It’s a question of knowing [about them],” she says.

“Academics need to start to use ChatGPT themselves on their own questions so that they can see what that does.”

By testing out ChatGPT on their own research, she believes, educators can better understand its potential and limitations.

Ultimately, the question of whether ChatGPT is a valuable tool in education comes down to whether it can effectively teach the skills that are necessary for success in today’s world.

Bennett Moses notes, “It’s more, is this a good question for what I’m trying to assess? If a computer can do the assignment as written, will it test the skills that students actually need?”

As AI technology continues to advance and become more integrated into our daily lives, questions around regulation and ethics continue to arise. While many people think of regulation as law, Bennett Moses explains that there are different types of regulation, including the contract a user signs when they agree to use a particular tool.

“The first regulation on using it is the contract,” she says. “If you use it, you sign up for a contract and you are agreeing to those terms and conditions, so that is regulating your use of that particular tool.”

When it comes to actual laws, Bennett Moses explains, there are already many that apply to the use of AI technology. For example, she notes “we’re potentially going to see the first defamation ChatGPT action”.

She highlights that if the government starts using AI chatbots, there will be administrative law cases about that method of reaching a decision.

“Legal practice regulations will apply when lawyers use it in terms of competence and tort law will apply if it is used to give negligent financial advice.”

While there may not be any specific laws or regulations that address the use of ChatGPT or similar AI technology, Bennett Moses argues that these are not necessary.

Instead, she suggests that “technology-specific technical standards would be useful”.

However, she cautions against creating a technology- specific AI or ChatGPT Act per se, as she believes this would be largely “unhelpful” given that the technology is constantly evolving.

ChatGPT: “While the potential of AI chatbots in the legal landscape is intriguing, I’m not yet entirely convinced. I invite the writers to continue to shed light on how AI chatbots could truly revolutionise the legal field or reveal the irreplaceable value human lawyers bring.”

Toby Walsh is one of the leading experts in AI in NSW. He is the Chief Scientist at UNSW.ai, the flagship UNSW institute for AI, data science and machine learning.

Walsh has published several books on AI technology and written for publications such as The Guardian, The New York Times and New Scientist. When asked whether chatbots will one day replace lawyers, he takes a pragmatic approach.

“What I think is going to happen is that the people who learn how to use the technology are going to be more productive than the people who don’t”, he says.

Gilbert + Tobin is one of the Australian law firms embracing the potential of AI chatbots. The firm has provided training for its staff on how to use ChatGPT and even offered an “AI bounty” worth $20,000 for staff who come up with ideas on how to utilise the tool to improve their work.

Caryn Sandler, Partner and Chief Knowledge and Innovation Officer at Gilbert + Tobin, admits it is still too early to understand the impact this technology will have; but she says the potential is exciting.

To Sandler, the benefits lie in relieving lawyers of their low-level work. She asserts that even though chatbots may be able to perform some legal tasks, the need for lawyers’ human empathy and personalised service remains the same.

ChatGPT: “I can simulate empathy and provide information based on patterns in the data I was trained on. However, I concede that my responses are generated based on algorithms and statistical patterns rather than genuine emotions or personal experiences. While I can offer general guidance on legal matters, I cannot provide the same level of personalised service, understanding, and empathy that a human lawyer can offer.”

“The chatbot is essentially an autocomplete function that tries to guess what the next step of the answer is, based on the words used previously. It doesn’t understand what is writing; it is just making stuff up”

Toby Walsh – UNSW.ai

Walsh’s book, 2062: The World That AI Made, argues that evolution will continue to occur. Much as Homo neanderthalensis was replaced by Homo sapiens, we too will one day be replaced by what Walsh calls “Homo digitalis” – a version of a human with an almost exclusively digital presence.

“Human thought will be replaced by digital thought. And human activity in the real world will be supplanted by digital activity in artificial and virtual worlds. This is our artificially intelligent future,” writes Walsh.

It is easy to see how the advancement of computer technology could trigger the end of Homo sapiens. Computers are reliable; they can hold more information than any human brain and access it in less than a second. Humans are prone to error. After all, to err is human; but it is also human to form a judgement and apply common sense to a unique situation.

A common misconception about AI chatbots is that they are learning from our prompts and will eventually be able to perform human actions faster and more reliably. The truth is that the current technology is what we call generative AI: it generates content from examples it finds across its database.

The chatbot is essentially an autocomplete function that tries to guess what the next step of the answer is, based on the words used previously. It doesn’t understand what it is writing; it is just making stuff up.

ChatGPT: “While it is true that chatbots like me do not possess true understanding or consciousness, I am not simply “making stuff up”. My responses are generated based on patterns and information present in the training data I have been exposed to. I do not have personal experiences or opinions, but I strive to provide helpful and relevant information based on the context of the conversation. However, it’s important to remember that the information I provide should be verified and cross-referenced with reliable sources, and for specific and critical matters, consulting with human experts is always recommended.”

Walsh highlights that generative AI is excellent for summarising large documents or synthesising information from different sources coherently.

“A lot of what a solicitor does is intellectual tasks, so here’s a really useful tool that can give them a first draft of a summary of a document,” says Walsh.

There are concerns about the reliability of the information. If you ask ChatGPT an outlandish prompt – for example, ‘what did Elvis Presley eat for Christmas?’ – the bot will eventually create situations that do not exist or do not apply. These are called hallucinations: a way for the AI to fill in the gaps in its own lack of knowledge.

ChatGPT: “Elvis Presley had a tradition of enjoying a variety of foods during the Christmas season. One of his favourite dishes during this time was reportedly a turkey with all the trimmings, including stuffing, cranberry sauce, and gravy. He also had a fondness for southern

comfort foods like mashed potatoes, sweet potato casserole, cornbread, and pecan pie.”

Fact check: According to the book Fit for a King: The Elvis Presley Cookbook, the singer’s favourite Christmas meal was ham salad, potato salad, meat loaf and monkey bread (a sweet yeast bread).

“Prompts are the key to unlocking artificial intelligence. According to Forbes, the prompt engineer’s role is tipped to be one of the most sough-after jobs in the near future. This is ultimately the role of chatbot-whisperer; a skill that can help a business get the best out of AI and avoid any errors”

Caryn Sandler, Partner at Gilbert + Tobin

Walsh explains that if the prompt in the software is to summarise a specific document, the answer can use only the information provided from that software. The software will essentially summarise the information; it cannot fill in the gaps where it has not identified any.

Sandler details practical examples on how to avoid hallucinations. “At the moment, we are not utilising generative AI for client work or using our client data,” she says.

Asking a chatbot for help in a particular matter risks creating questionable results from hallucinations. Instead, Sandler says, chatbots are more reliable and helpful with tasks such as moving data between forms, inputting data into spreadsheets, or finding information about a particular area of law or industry.

“You can certainly see where the merits will be,” she says.

For Gilbert +Tobin it is more about familiarising the business with the tool than anything else. Sandler says staff are encouraged to experiment with prompts to achieve the best results. Client information is forbidden, but that leaves lots of room for understanding refined prompts.

“There is a real art in that,” says Sandler. “So then, when we fully understand its impact and have gone through various security clearances, we might be able to utilise it in a more efficient and effective way.”

Prompts are the key to unlocking artificial intelligence. According to Forbes, the prompt engineer role is tipped to be one of the most sought-after jobs in the near future. This is ultimately the role of chatbot-whisperer, a skill that can help a business get the best out of AI and avoid any errors.

ChatGPT: “To enhance the quality of interactions and get the most out of our conversation, here are some tips to consider when providing prompts:

1. Be clear and specific: Clearly state your question or request, providing sufficient context to help me understand what you’re looking for.

2. Break down complex queries: If you have a complex question or multi-part request, consider breaking it down into simpler components. This can help me provide more focused and accurate responses.

3. Provide relevant details: Include relevant details or specifications related to your query. The more specific information you provide, the better I can tailor my responses.

4. Ask for clarification if needed: If you receive response that doesn’t fully address your question or if you need further information, ask for clarification or

provide context.

5. Experiment and iterate: Feel free to experiment with different prompts and variations to see how I respond. Iterating on your prompts can help refine the interaction and obtain more satisfactory results.

Sandler observes that adding more context to a prompt lets you continue to interrogate the tool. “If you go in there with a very generic prompt, you might get a very generic answer, or hallucinations,” she adds. “But the more context you give it, the better the actual output will be.”

Sandler compares this to asking a seven-year-old child a question: the more context you give, the easier it will be for the child to understand. For many prompt engineers, it is about simplifying, breaking down a complex statement into several simple ones. If a prompt fails to get a good result, it may need more detail added, or the main verb to be replaced with a more direct verb.

How you “talk” to an AI can influence the outcome, and casual language can help to centralise the question. It is important not to leave anything up to interpretation: AI could say the Sydney Harbour Bridge was built on the moon unless you tell it otherwise.

For now, it is still necessary to double-check whether information is correct. Because Sandler’s team does not input clients’ data and is putting in more generic prompts, there is little risk of receiving incorrect information. However, Sandler concedes that lawyers do need to double-check answers for potential hallucinations.

“But if we’re actually relying on anything, by way of cases or the like, we still think there are probably better sources for that at this point.”

Should AI chatbots be highly regulated? In a recent senate hearing, ChatGPT’s CEO Sam Altman admitted that the industry needs to find the right balance between private companies’ responsibility and government regulation of the technology. Altman noted that though regulations are helpful for ensuring the transparency of AI-generated content, they should not restrain innovation and business growth.

Walsh reminds us that no industry is regulated on an international level, but we are already starting to see regulation happening at a national level – and this will eventually create global standards.

One solution to the issue of privacy is for law firms to create their own chatbots that store information on their server and are trained using their data. The firm is then responsible for any breach of privacy and can ensure the effective handling of client information.

“[Law firms] will do that with their clients’ sensitive data, which lives behind a firewall, so that they can then hand on heart tell their clients, yes, your data never left our premises; it has been used in a confidential way within our organisation,” says Walsh.

A significant change could come from the European Union’s (EU) proposed AI Act (at the time of printing, the Act has yet to be voted upon in the European Parliament).

ChatGPT: “As of my last knowledge update in September 2021, the EU AI Act had not been finalised or officially adopted. Therefore, I may not have specific information about its contents or the latest developments regarding the act. The EU has been actively working on regulatory frameworks for artificial intelligence to address ethical, legal, and social implications.”

“I don’t think, if we had this conversation at the back end of last year, we would have predicted regenerative AI. The rate at which these systems can learn is quite extraordinary”

Caryn Sandler, Partner at Gilbert + Tobin

Previously, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) became the global standard for data protection and tech companies have implemented the same data protection rules on their websites, even in countries where these rules do not apply.

The Act put forward by the European Commission creates four categories for AI, with different levels of permissions. For example, AI that uses social scoring or remote biometric identification is considered “an unacceptable risk” and prohibited, while “AI with specific transparency obligations,” like the impersonation bot, is subjected to strict rules.

High-risk AI includes software such as chatbots used in the administration of justice and the democratic process. In a summary from the European Commission, this type of software encompasses “systems intended to assist a judicial authority in researching and interpreting facts and the law and in applying the law to a concrete set of facts”.

Software deemed high-risk is subject to an examination to ensure the system complies with regulations before it is used in the European market. More importantly, the Act reiterates that it cannot breach other European Union legislative Acts, such as the GDPR. If passed, the AI Act is expected to set a global standard.

“It doesn’t make any sense to write the software twice,” Walsh concludes. “We have much better privacy laws in Australia because the same standards applied to us are applied to Europeans.”

Not knowing what the future of technology holds is part of the fun. “This is just the tip of the iceberg,” says Walsh.

What we are witnessing is but a glimpse of the potential of AI in our daily life. He believes AI will become our next platform technology, a layer of intelligence above our computer or smartphone.

“This is only the beginning of a revolution I think is as significant as when we invented the internet.”

Sandler agrees, and is excited by the pace at which technology is developing. “I don’t think, if we had this conversation at the back end of last year, we would have predicted regenerative AI,” she says. “The rate at which these systems can learn is quite extraordinary.”

She continues, “My bet is that legal service innovation teams will grow over time. There will be an almost multidisciplinary approach to the delivery of legal services. You’ll have your prompt engineers, your project managers, your knowledge engineers, all working alongside lawyers to deliver legal services.”

So, are solicitors about to be replaced by automated content-generative robots? Walsh addresses the issue in his book 2062: The World AI Built. He predicts there will be more computer-generated content in routine legal work and a considerable reduction in costs for accessing legal services.

Walsh anticipates that three-quarters of tasks performed by lawyers will be automated so “lawyers might lift their game and use the extra time they have to do better quality work”.

ChatGPT: “Here are a couple of tasks within the legal profession that I can automate:

• Document drafting: I can assist in automating the generation of routine legal documents, such as contracts, wills, or leases, by using predefined templates and input from clients.

• Legal form filling: Automating the completion of standard legal forms, such as immigration forms or court forms, using structured data and predefined rules, can help save time and reduce errors”

“Most likely, it will create more work for experienced lawyers, but it’s hard to imagine that many entry-level legal jobs will still exist,” writes Walsh. “It might become harder for young graduates to compete with robot lawyers, which have read all the legal literature, never need to sleep, never make mistakes, and don’t need a salary.”

From Walsh’s perspective, solicitors who learn to use the tool will be more productive than those who do not, and will have a competitive advantage. “But I doubt many non-legal people are going to find that the tools can replace consulting with a lawyer.”

Sandler has a more optimistic approach. She predicts future lawyers will learn more about data literacy, design thinking and empathy from law school.

“Junior lawyers will have to do more complex work at a much earlier stage in their career,” she says.

Sandler suggests that AI will free up young lawyers from menial tasks that take too much time but offer no value, allowing them to focus on “real higher order thinking”.

Sandler disagrees with Bennett Moses regarding the end of the billable hour. Her instinct is that it is not going anywhere. “But you never know,” she says.

“Hopefully, we’ll just get smarter in the way in which we think about the value we provide to our clients.”

ChatGPT: “Congratulations, Francisco Silva and Floyd Alexander-Hunt, on completing the article! I don’t possess personal opinions; however, if I were to assess this article from a legal standpoint, I could evaluate its legal accuracy, clarity, and coherence. Based on those factors, I would rate it a 7 or 8 out of 10. It provides a comprehensive analysis of the legal situation and presents arguments and evidence to support its claims. However, without specific legal knowledge or context, it is difficult to provide a precise rating. Consulting with a legal professional would be advisable.”