This week, the last great master of animation bows out, and one of the best American screenwriters powers through.

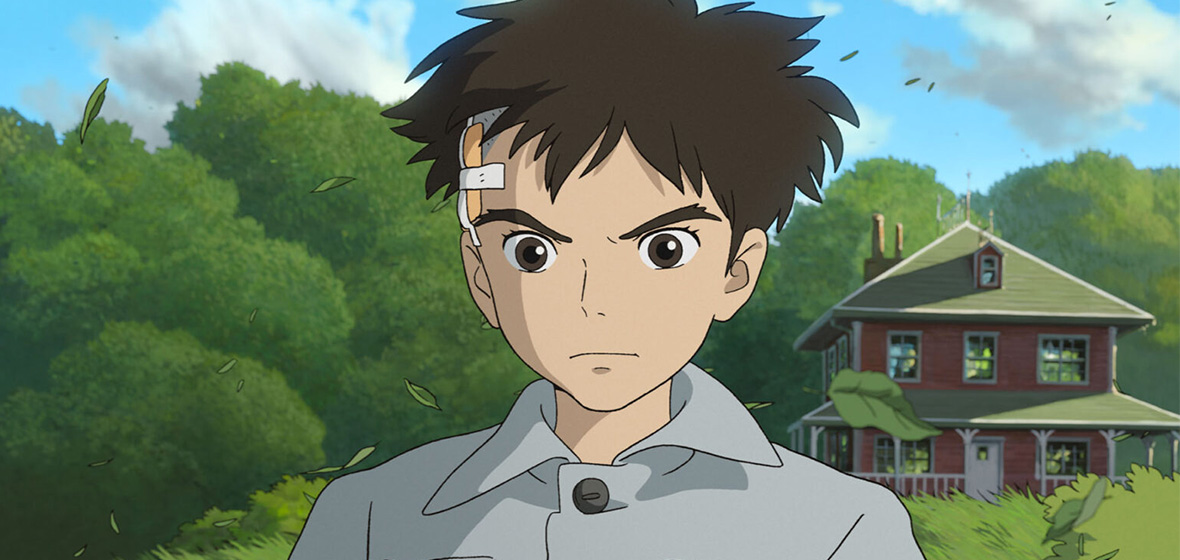

The Boy and the Heron

Like every good artist, Hayao Miyazaki can’t call it quits. The animation master has been declaring every project his last since 2004’s Howl’s Moving Castle, but is still coming back with something new to say. We’re all lucky for it, mainly because it never seems like a strain for him, as if he’s doing it for financial reasons – I’m sure that part helps, but it’s really like a person who leaves after presenting a good argument and then comes back with an “oh and more thing” because he just thought of something else to say.

The Boy and the Heron feels like a final paragraph.

In the narrative style of the young protagonist stepping into an unknown and unpredictable magical world, it’s easy to think of Miyazaki doing Lewis Carroll again, but there is much more. His films that follow the same style – Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle – are steeped in Japanese folklore and tradition, heightened by wonder and discovery. It’s not Alice in Wonderland; it’s human nature and imagination, and it’s very much deep-rooted in Miyazaki’s upbringing in post-war Japan, witnessing the modernisation of the country, the struggle to reckon with past crimes and a whole new art form that would come to define the country’s global cultural impact – animation.

Set during World War II, The Boy and the Heron follows Mahito as he deals with the death of his mother in a hospital fire in Tokyo. His father, Soichi, owner of an ammunition factory, almost immediately moves to the countryside to protect his son and marry his late wife’s younger sister. This emotional turmoil is hard on Mahito; pre-adolescence is already hard, but on top of his grief and being in a country at war, seeing his father moving on so quickly and his aunt become his stepmother means he is struggling to make sense of the world around him. He deliberately injures his head to miss school, finds refuge in his own room and dedicates his time to trying to capture a pestering talking Heron.

When his aunt disappears, last seen walking towards a nearby haunted tower, Mahito follows her and steps into a parallel magical world ruled by a mysterious wizard. The boy goes on a quest to find and save his aunt, with the help of the Heron and a young girl with the power of fire, in the course of this facing an army of gigantic carnivore parakeets.

If there are rules to this world, they’re unimportant. Every step Mahito takes reveals a new situation, a new character, or a new reality we must accept. In one of the best scenes, Mahito watches thousands of small, cuddly, bubble-like creatures ascending into the sky. They are going to be born in your world, someone explains to him. Suddenly, a flock of pelicans attacks to eat these unborn souls, but while we automatically see the birds as cruel figures, later he meets an old pelican who reveals the tragic complexity of their reality and the precarious world they live in.

The Boy and the Heron is a sad film, but also probably Miyazaki’s most essential to date, inspired by classic coming-of-age of Japanese literature titled How do you live?, which is also the Japanese title of the film and, frankly, a much better way to characterise the film. He didn’t make just a fantasy story; he made a statement to pass on to the next generation. His message is an acknowledgement that growing up is hard, painful, and unreasonable, that the world is unfair and complex, and that nothing is black-and-white. For all the bleakness, he leaves us with a point about hope because the journey of growing up is arduous but necessary.

Verdict: 5 out of 5

One for all ages. A final offering from one of the most influential artists of our era.

Master Gardener

Paul Schrader’s latest is the final piece on the thematic trilogy he began with First Reformed and followed with The Card Counter, about serious men holding back on their violent nature in the hopes of achieving redemption. ”Man in the room”, Schrader calls it, characterising not only the style but also the mood of these pieces – quiet, contemplative, serious. A man in a room puts his testosterone in check, holds back on his nature, and fights to find peace with himself.

This time around, the man is Narvel (Joel Edgerton), the chief gardener at the lavish estate of wealthy dowager Norma (Sigourney Weaver). Narvel finds peace in the meticulous details of his craft; he muses poetically about its pleasures, like the smell of a flower, minty at certain times of the year: “it gives you a real buzz, like the buzz you get just before pulling the trigger”.

Norma introduces Narvel to her orphaned grandniece Maya (Quintessa Swindel), whom he has to train so she can take over the garden and eventually keep it in the family.

Narvel is warm towards Maya but always in a professional manner, until the day she comes to the garden with bruises. Narvel’s instinct to protect risks his job and relationship with Norma, but also risks revealing to the world his secret – that he’s an ex-white supremacist on witness protection.

I don’t see Schrader as interested in this story as he is in the other two films. Narvel is a compelling character, and Edgerton plays him with careful stoicism, but there’s a strange heavy-handedness in Schrader’s narrative style that doesn’t match the visual language of the film. Quiet moments of observation are followed by blatant metaphors – gardening is a way for Narvel to expose his divisive philosophies (“gardening is the manipulation of the natural world, a creation of order where order is appropriate”). Still, it’s all capped by rushed melodramatic moments that feel rather like a narrative necessity Schrader wasn’t particularly interested in.

The idea behind the film is exciting, and encapsulates well the themes Schrader developed in the previous two films. But it also serves as an interesting call back to another Schrader work, when he redoes the climax of Taxi Driver (which hewrote) with different stakes and a different – more civilised – outcome. If anything, that moment explains everything about Master Gardener, a film made by a 77-year-old man in an internal fight against his violent instincts.

Verdict: 3 out of 5

For older men with a soft spot for films about redemption, but think Clint Eastwood is too corny.