Rating: ****

It’s an understatement to say I was excited to see Licorice Pizza. Paul Thomas Anderson has been my favourite contemporary filmmaker since my impressionable 16-year-old mind caught Magnolia in the cinema. My cinephile taste took on a journey that accompanied his subsequent filmography, and it felt somehow like I was seeing my best friend settle his place in the artistic pantheon.

A film critic who loves PTA, what a surprise, but you have to understand he’s one who continuously shows growth in a whole generation of filmmakers. Years ago, I caught an advanced screening of his Thomas Pynchon adaption Inherent Vice. He surprised everyone by introducing the screening in a mix of needy excitement and awkward discomfort. It was evident he wanted everyone to love his film. It was apparent he didn’t know how to show express it. During a longer-than-usual pause, someone in the back of the cinema shouts, “you’re a good man”, and that’s right, it’s exactly how he comes across in his oeuvre. His art speaks beautiful truths like we hope only good men can.

That truth is put to the test in Licorice Pizza. A film so personal, it’s almost private. You ever wondered how it was to grow up in the 70s in the San Fernando Valley? Here it is in its most nostalgic wonder. As perplexing as it, even the title only makes sense to those there at the time. Licorice Pizza was a chain of record stores from California purchased by a retail-mega-corporation in the mid-80s. Licorice Pizza is a remnant of a past that doesn’t exist anymore.

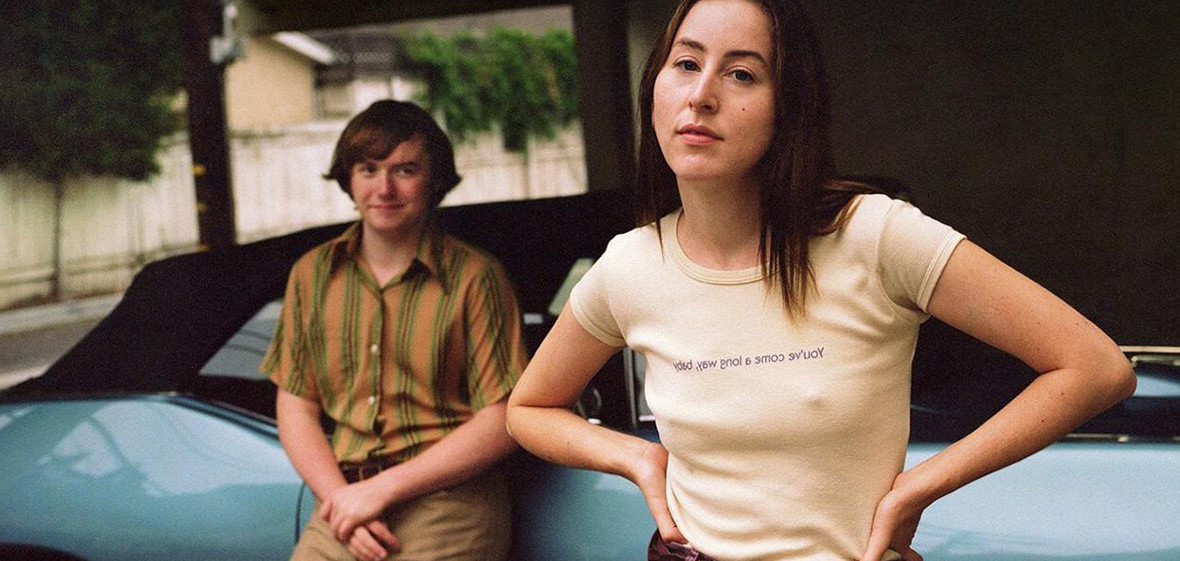

PTA collates his story from a series of episodic moments about a young 15-year-old kid Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman, son of deceased, and past PTA collaborator, Phillip Seymour) from the moment he meets the beautiful and decade older Alana (Alana Haim). Gary is rarely in school, driven by that American will to succeed. Instead, he spends his days either working as an actor, gathering a rather humble portfolio in films, TV, ads and theatre, or finding the next business he trusts to be the next big thing. He owns a PR company, tries to sell water beds, builds a pinball machine bar. All with the help of his other 15-year-old friends, who all jump into each endeavour like a bunch of Tom Sawyers and Huckleberry Finns choosing a new adventure.

Alana is the exact opposite. Lost and aimless, she’s drawn by Gary’s endless proposals. In the end, Gary is still a horny teenager, and Alana finds at least a purpose of being, leaving the shackles of her over-religious household and finding her goal. At the start, that of being an actress, then as a businesswoman, finally perhaps politician?

The film has zero to little plot, similar to another PTA masterpiece, The Master, but each episode is told and developed with richness and love. Many of it is taken from stories PTA lived himself or others he heard growing up in the Valley. But they all paint this patchy tableau of memory and nostalgia. It reminds me of two of his other films, also set in L.A. during the Nixon presidency – Boogie Nights and Inherent Vice. While the first is a rose-tinted memory of an industry PTA was idealising, the latter is another person’s idealised rose-tinted memory. This one has a more complicated relationship to the place.

In probably the film’s best moment, the group has to deliver a waterbed to Barbara Streisand’s house and are received by her infamous partner Jon Peters (Bradley Cooper). The entire sequence is prime Thomas Anderson, like Alfred Molina’s hectic drug den in Boogie Nights, as a series of increasingly unfortunate events threaten to escalate into chaos with this unpredictable character at its centre. Cooper is so tremendous in the role he manages to even steal a scene where he’s only acting in the background.

In another moment, Alana goes on a date with Jack Holden, a fictitious actor made from the same cloth as Steve McQueen. He’s drunk at the bar, letting himself be charmed by the young Alana when Rex Blau (Tom Waits doing a pretty solid drunken John Sturges) joins them and convinces them to participate in an impromptu action stunt to entertain the patrons. Both scenes are beautiful highlights precisely because they cast a pessimistic light into Anderson’s memory. In those moments, it feels like Anderson doesn’t necessarily love L.A., but he hates to love it that much.

For all the beauty and truth in the film, Licorice Pizza commits a big sin. I can’t overlook one that makes me drop one star in this rating. During the first 20 minutes, we are introduced to Jerry Frick (John Michael Higgins), a restaurant owner with an interest (read fetish) in Japanese culture. In the two scenes, he presents two different Japanese wives who the protagonists can’t differentiate (because they look the same aha, get it?)

The scene is grotesque and painfully unfunny, only made worse by the many, all white, film critics cackling at the absurdity during the screening I was in. It may seem the film is laughing at Jerry, a real character from back in the era, but apart from the offensive accent, he’s a lovable buffoon, more ignorant than evil. The wives, on the other hand, are not given any personal traits apart from “serious Asian dragon lady”, such a strange and lazy turn for Anderson, a filmmaker so meticulous who instils life to even the more pedestrian background character.

The worst part is those entire scenes could have been removed, and nothing would have changed. They add absolutely nothing to the characters, the story, or the world it’s trying to represent. The most exciting payoff from that moment is when it’s revealed, later, that the Japanese restaurant that advertises “real Japanese waitresses” actually employs white girls in yellowface. There is more meat and depth in that revelation than in the five minutes of offensive pantomime.

The sour taste the two scenes left me with took time to pass. Even now, I’m still baffled by their inclusion. I want to say they didn’t spoil my overall enjoyment of the film, but it’s hard to shake it off. A moment so unnecessary it can almost be a sellout. We were so close to genius here.