Broker

Hirokazu Koreeda’s Broker is the closest we’ll get to a thriller from the Japanese auteur. He’s a master of the deceptively simple drama that starts off from a clear concept (say, Like Father Like Son, where two very different families discover their sons were mixed up at birth) and is then explored through its complex emotional entanglements. It has been 19 years since Koreeda’s Nobody Knows, and I still haven’t recovered from it.

As time has passed, Koreeda hasn’t lost his touch at breaking hearts. His films grow stronger with time. Like Kiarostami’s, his stories resonate with anyone with a heart and a brain. They have been constructed to make you connect with their characters while questioning the dubious aspects of society. I love the Dardenne brothers, but I can see why some cinephiles find them patronising. Koreeda is too warm, and cares too much, to fall into that trap.

Broker is an interesting departure for the filmmaker. It’s almost a genre film, and, as I mentioned earlier, the first time he’s shooting outside of his native Japan – moving only across the pond to South Korea. The two countries have a contentious diplomatic relationship but share cultural similarities, so there’s nothing in this film that looks to be lost in translation. In fact, Koreeda’s status as a foreigner gives him the chance to observe small details that may have passed by any local filmmakers.

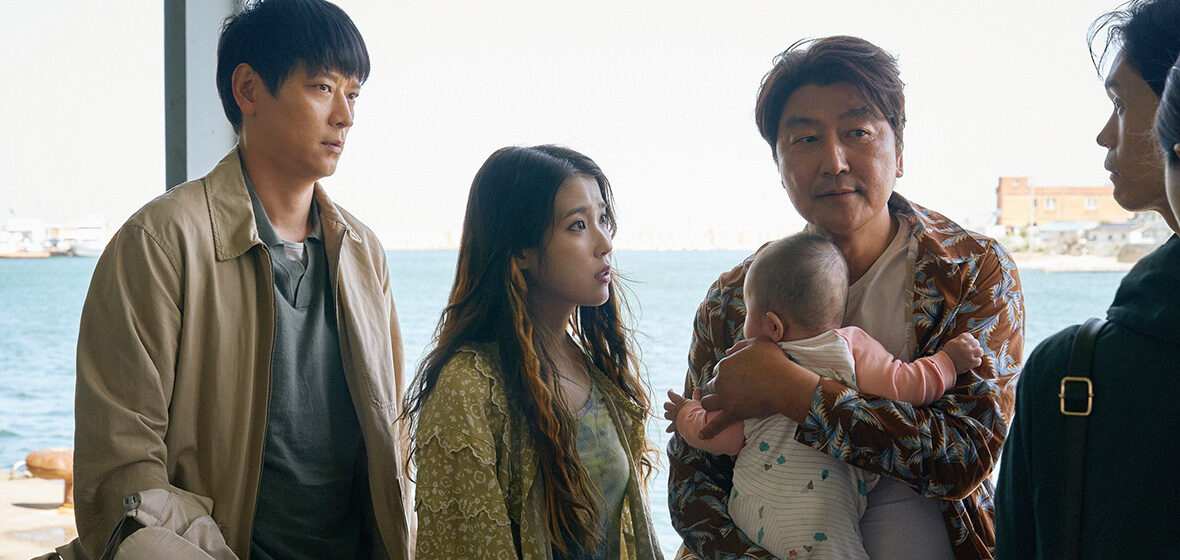

The first strength of a Koreeda film is the premise. Moon So-young (Kpop artist Ji-eun Lee, stage name IU) is a young mother who abandoned her new born son at a local church. The child is collected by Ha Sang-hyun (Parasite’s Song Kang-ho) and Dong-soo (Gang Dong-won). They are brokers, people who collect abandoned children before they are registered with churches and orphanages so they can sell them for adoption on the black market.

The day after she abandons her son, Moon regrets her decision, and while she is looking for the child she encounters the two men. The chance to give her son to a loving family, she decides, is better than abandoning him in an orphanage. So she accompanies the brokers, caring for the infant as she does so, and hoping to ensure he will end up with the right family. In the process, the three adults do their best to dodge Su-jin (Bae Donna), one of the police officers on their tail waiting to arrest them as soon as a transaction is completed.

What Koreeda does well is carefully explain that, if you look long enough, there is an ethical dilemma at the heart of morality. Ha and Dong-soo were never going to be petty heartless criminals, and Moon isn’t just an inconsiderate mother. The moment she returns to retrieve the infant from the orphanage, she realises the prospects of her child finding a stable life there are slim. The brokers are fixing an issue broken by society.

But there is a need to be responsible for one’s actions, Koreeda is demonstrating, even if by taking those actions you’re doing the right thing. Koreeda doesn’t want Moon and the two men to be viewed as exemplary heroes. Their characters reveal a problem hurting many Korean families. The film shows that they are victims of their own circumstances: of their own fragmented upbringing, of inequality, of a social structure that leads people to take desperate measures.

The emotional entanglement at the start of the film turns into a loving road trip in the middle, before reality comes crashing down. It’s interesting that the ending doesn’t have the emotional punch the start promises. Maybe it’s because we already know those characters so well that the conclusion is just a deflating realisation that society will catch up with you no matter how hard you try to escape from its clutches. In that sense Broker is not just a mirror to South Korea, but to any place a unregulated capitalist society can identify with.

Verdict: 4 out of 5

For everyone who loves a good dose of social realism. The humane and gentle kind.

Linoleum

Linoleum is the debut feature of writer-director Colin West, and it’s a complicated time-bending sci-fi quirky romantic story that would have been hard to wrap one’s head around if it were made by an experienced filmmaker – let alone a first film.

This film is not easy to categorise, but if I’m giving it a go it would be this: Donnie Darko made by Michel Gondry. If that doesn’t pique your curiosity, then nothing the film has will convince you. But if you’re still reading, this then maybe emotional-concept sci-fi films are an itch you’ve been dying to scratch.

Cameron (Jim Gaffigan) is the presenter of a kids’ science TV show on the local TV channel. It’s a whole DYI production made in his garage, with cardboards and trinkets. It looks like a the set from the dream sequences in Gondry’s The Science of Sleep – it’s charming like that. Our world must be a different place: nowadays something like this would be catnip for the kids of hipster millennials, but in the film it airs at midnight and no one watches it.

Cameron is married to Erin (Rhea Seehorn), who used to be his co-host but now works in a local science museum. Their daughter, Nora (Katelyn Nacon), is the eccentric nerdy girl in high school who just happens to develop a crush on Marc, the new kid in town, whose father (also played by Gaffigan) is an ex-astronaut who is set to replace Cameron in a new revamped version of his tv show.

Then a satellite falls on Cameron’s house, like the plane turbine in Donnie Darko, kickstarting a series of events where each character enhances their obsessions and face their own fears . It’s hard to explain the rest of Linoleum without unveiling some of the magic. The story cuts from Cameron’s obsession about building a rocket in his backyard from the scraps of the satellite to Erin’s malaise resulting from having to settle for a soulless corporate job while her husband plays in a garage all day, and Nora’s relationship with Marc and his complex father issues.

Everything is interwoven rather charmingly, and a sense of American suburbia ennui permeates. Linoleum feels like a film from 2004, when alternative culture was both sad and twee. A time when Zach Braff was trying to be a voice of a generation, but it was someone like Charlie Kaufman who more effectively tapped into that teen restlessness. For better or for worse, Linoleum is clearly a film by someone who lived through those decades but never managed to contextualise his anxieties until now, in his mid-30s.

The ending is better left unmentioned here. Without revealing much, it tries to do a clever take on Donnie Darko’s ending, but in a far more complex way. The mechanics are not particularly well thought out, but I did appreciate the courage it took to take the story there.

But, most importantly, this film makes you feel things. Because that was always the point. The magical science fiction element was just a conduit for tackling issues of arrested development, untapped potential, and generational trauma. Everything else is background noise.

The vibes. Linoleum is all about the vibes. And these ones are immaculate.

Verdict: Strong 3 out of 5

For people in their 30s who are acutely aware that life didn’t pan out the way they wanted it to.