In a polarised world, where many feel increasingly removed from government decision making, does deliberative democracy offer a way to restore our faith in democratic processes?

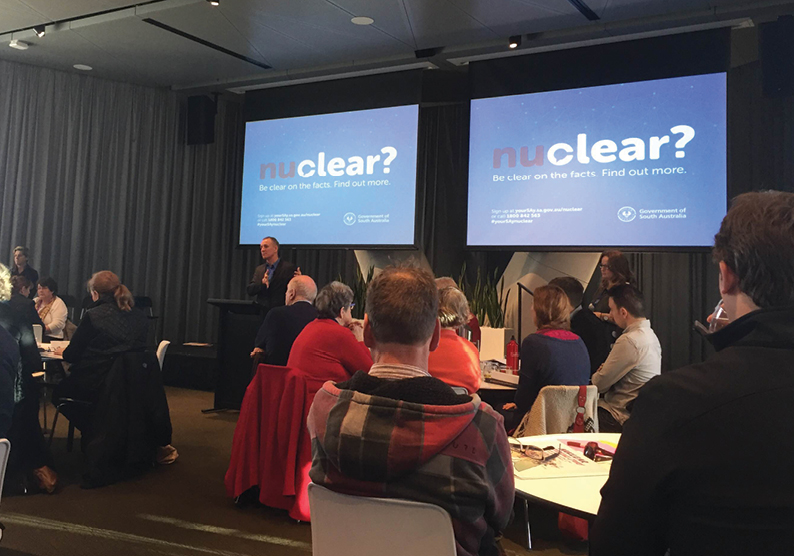

It’s mid-2016 in Adelaide. It’s been raining for days. Wind relentlessly buffets the city. 52 random people are picking their way around a swarm of raincoated protestors and into a room brimming with journalists. Cameras and boom mics are thrust in their faces. There’s Stanley, a 35-year-old software engineer from Torrensville. There’s Jenny, a 56-year-old screen printer from Port Augusta and Khatija, 38-year-old business owner from Adelaide. The list goes on. They’re all here for one thing: to discuss the prospect of establishing an international nuclear waste storage facility in South Australia. They’re here for a citizens’ jury.

A strange, confused tension reigns. Nuclear things are a touchy topic in South Australia. Rural parts of the State, Maralinga and Emu Field, were used for nuclear weapons testing in the ’50s and ’60s, and the land there—home to multiple First Nations peoples—remains contaminated and uninhabitable today. South Australia has the world’s largest known single deposit of uranium which supports an industry for mining, milling and exporting it. Over the years, a political forever-war has raged between those wanting to exploit this natural resource and those wary of the stakes and costs. Indeed, as the citizens’ jury on nuclear waste deliberated, a once-in-50-years storm caused widespread blackouts, for which many blamed an overreliance on renewable energy and pointed towards nuclear power as an alternative. It’s a complex, generational issue that has increasingly polarised the people of South Australia. Partisan positions are set. Consensus seems impossible.

So, you can understand why, as 52 random citizens arrive to report on the opportunities and risks of the nuclear fuel cycle, onlookers aren’t quite sure what to make of the scene. What good could this do? What could Shane, a retiree from Brompton, know about the nuances of storing, managing and disposing of high-level nuclear waste? The process is championed by people touting mini-publics and deliberative innovations that will put the ‘people’ back in ‘people power’. But can lay people really command such a vexed issue?

Those 52 citizens would hand down a report highlighting the key issues needing discussion, which would then be considered by a bigger, second citizens’ jury of 350 people. Over the course of three weekends, that citizens’ jury would call and listen to over 100 experts, deliberate, and refine ideas. It would generate a detailed report and an unequivocal answer to the question of whether South Australia should store and dispose international nuclear waste: no, under no circumstances.

Ultimately, the Premier at the time, Jay Weatherill, responded strategically. Although political momentum for the idea eventually died, he neither adopted nor denied the jury’s recommendations and called, somewhat ironically, for broader community engagement. The fact is the jury became heavily contested and split. Red dots—indicating a ‘no’ position—appeared on name tags at an early stage. The minority went rogue and wrote its own report. As they presented it, the majority heckled them, emulating the parliamentary dynamic they were supposed to bypass. Polarity, the very thing the jury was to solve, had infected the process. What was hoped to be a watershed moment became, for many, the day the deliberative dream died.

But what exactly is this process that dares to place power in the hands of strangers? What is deliberative democracy—and why, a decade on, are citizens’ assemblies once again capturing the political and legal imagination?

The philosopher, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, famously wrote in 1762 that “the English people believes itself to be free; it is gravely mistaken; it is free only during the election of Members of Parliament; as soon as the Members are elected, the people is enslaved; it is nothing.”

Deliberative democracy

Deliberative democracy considers authentic deliberation as the key ingredient to legitimising laws and political decisions. Of course, you’ll be familiar with our current model, representative democracy, where elections give successful representatives the power to make valid laws and political decisions. The two models aren’t mutually exclusive and are generally considered to complement each other. Indeed, traditionally, Parliament has been seen as the deliberative element of our representative democracy. Bills are debated, questions are asked, inquiries are conducted, public submissions are sought, and votes are made. It’s a fundamental element of the rule of law: procedural integrity as to how laws are made prevents tyrannical government and the arbitrary exercise of power.

But, in the past 50 years or so, deliberative democrats have become sceptical of whether this process constitutes authentic deliberation. Across Western democracies, houses of Parliament have become polarised and intense partisanship means they tend to attack and defend rigid policy positions, rather than discuss open questions. The influence of wealthy and powerful interest groups has grown. Political engagement with the public resembles marketing, reducing constituents to consumers. Misinformation pervades most major law reform proposals. The result is we often end up with laws and policies that don’t reflect the so-called will of the people or are weak and ineffective.

All this has a huge impact on trust in public institutions. According to the 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer, 64 per cent of Australians believe politicians are lying and nearly one in three (and over 50 per cent of those aged 18-34) see hostile activism as a legitimate way to drive change. With that last statistic in mind, it’s hard to deny law is losing its procedural validity and, with it, its normative power. And this isn’t just an Australian phenomenon. A 2025 OECD report, Government at a Glance, found that, across the 38 member countries, only 37 per cent of the population trust their national government.

“How do we get sound decision-making in a way that’s not polarised or taken over by partisan interests?” asks Ron Levy, a public law professor at the Australian National University. “We have division on questions we need to answer, but also a lack of trust in institutions. If we don’t trust the decision-makers who are making decisions of utmost importance, then we don’t necessarily accept their decisions.” The rule of law is nebulous but at its core is the question of what makes laws legitimate. It goes to the heart of legal theory. Is law something natural, inherent that we are trying to discover, or is it a mere fiction we have declared into existence? How does the consent or attitude of the governed fit into that? The OECD report found that political agency was the most impactful factor effecting trust: 69 per cent of those who believed they have a say in government decisions reported high trust in that government, whereas only 22 per cent of those who lack a voice felt the same.

Others have been decrying representative democracy even before modern issues like polarisation and misinformation arose. The philosopher, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, famously wrote in 1762 that “the English people believes itself to be free; it is gravely mistaken; it is free only during the election of Members of Parliament; as soon as the Members are elected, the people is enslaved; it is nothing.” The ideal of local MPs walking the streets, talking to their constituents only seems to happen around election time. And are these performances real consultation? Their policies are typically preordained and firm.

Marjan Ehsassi, a former litigator turned deliberative democrat in Washington DC, coined the term ‘voice insecurity’, reconceptualising political participation, or at least the opportunity for it, as a basic human need on par with food and shelter. It’s an intriguing way of understanding the malaise that has spread throughout Western democracies and the rise of populism. It echoes the Aristotelian idea that ‘man is a political animal’; that we can only exist as part of a broader socio-legal structure. From that perspective, to imagine (like Hobbes or Locke do) that humanity existed before such a structure—in the so called ‘state of nature’—is like imagining we existed before food; it doesn’t make sense. Are we a conglomeration of individuals choosing to socially contract with each other, or is our collectivity something more innate?

For Ehsassi, ‘voice insecurity’ is particularly bad in the US at the moment. “Except for an infrequent poll,” she says, “no one [elected representatives] actively seeks your input, asks for your priorities, or tries to get feedback on how to address public problems.” In 1978, when Ehsassi was 11, she and her family moved back to Iran from New York. The very next year the Iranian Revolution established the Islamic Republic of Iran. Ehsassi’s life would take a dramatic turn and, as a bright young woman, she was excluded from the education system. Her experiences of voicelessness led her overseas, first to the law and then to international advocacy on the rule of law. Now, she helms the Federation for Innovation in Democracy in the US, working with people looking to implement consequential citizens’ assemblies. Her career has taken her around the world to controlled, closed legal systems where public institutions lack strong democratic traditions. But over time, she saw a change at home in the US that disturbed her. As unimaginable events in Washington DC panned out, Ehsassi recognised uncanny parallels with the system she grew up under.

“It reminded me of my own life in Iran and—” Ehsassi’s confident voice fades for a moment as we speak.

“It just felt really incomprehensible to me that I was living in this nation’s capital. Why is it that people are not engaged with their political institutions? There’s no way to hold government accountable. There’s no space in between elections for my voice to be heard in a way that is really consequential.”

Of course, in Australia there are Parliamentary inquiries, public consultation and human rights scrutiny which are certainly deliberative and impactful. The Law Society’s many policy committees do fantastic work discussing and providing feedback on emerging issues, draft legislation and court decisions. They connect not just the NSW legal practice, but also the swathe of everyday people involved in the legal system with the legislature. Their submissions are frequently factored into the laws and policies they are addressing. But, as deliberative mechanisms, processes of inquiry, consultation and scrutiny remain imperfect. While some are open to the public, they can be dominated by interest groups and tend to happen after a bill has been drafted or a policy decided.

There are also no enforceable penalties for ministers who entirely ignore or neglect the scrutiny and consultation processes. And, when laws are passed without recourse to mechanisms like the Law Society’s committees, they lose their normative weight and the rule of law is eroded. In November 2024, the federal government, with astounding expedience, passed 30 bills in a mere two days. Procedural neglect like this has slowly become more commonplace. Practitioners will recall the abolition of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal in 2023 and 2024 which was implemented through a legislative package of over 1000 pages. Stakeholders were given a month over the Christmas holiday period to scrutinise its operation. For the Criminal Code Amendment (Deepfake Sexual Material) Bill 2024, consultation was open for 17 business days. The Identity Verification Services Bill 2023? 13 business days. “The Law Council has been increasingly concerned that legislative processes are being rushed unnecessarily, lack transparency, and overlook key steps in the development process,” remonstrated Juliana Warner, the Council’s President earlier this year.

Processes of inquiry, consultation and scrutiny are probably the zenith of deliberation in Australia. Undoubtedly, we are better off with them but when it comes to fostering genuine, inclusive conversations and honouring our commitment to the rule of law, they are failing. And never before—in the face of declining trust in political institutions, political polarisation, misinformation, populism and democratic backsliding—has it seemed more imperative that democracy reassert itself as the way to govern people legitimately; that it ask itself, how can a system harness the normative power of law?

Deliberative democrats have a simple answer to that question: it needs to have inclusive, reasoned public deliberation that is untainted by the influence of power and strategy. Needless to say, this begs the question of how, in current institutional contexts and with millions of constituents, this could be possible in any modern democracy. That’s where citizens’ assemblies come in.

Citizens’ assemblies

Also known as citizens’ juries or deliberative mini-publics—citizens’ assemblies have emerged as a possible solution to this deliberative failure and the wider democratic languor observed in Western democracies.

“We use lottery selection, take 43 or so people, put them in a room and ask them to solve a difficult problem,” says Iain Walker, the executive director of the newDemocracy Foundation (NDF), which was part of the team running the South Australian nuclear waste jury. He’s sitting across from me in a meeting room at the Law Society. An overnight bag rests at his feet—he’s got a flight to Melbourne in a couple hours to front a Parliamentary inquiry—and his fingers are darting across the table, tapping emphatically as he speaks. NDF is a leader at implementing citizens’ assemblies around the world. Since 2004, it has run about 40 of them.

The idea is that, given time, resources and the right design, these juries of random people will make decisions in a more reasoned and open way than our representative democratic political system currently does. “We expose people to diverse and contested evidence, and we task them to find common ground,” says Walker, fully aware of how simple the concept is.

Quality deliberation means there must be a degree of reflection on personal values and openness to new information. Every citizens’ assembly thus needs to have a principled learning stage where subject-matter experts and relevant perspectives are called on. Then, with the assistance of skilled and independent facilitation, members discuss trade-offs and values, and look for consensus on the issue. Finally, they need to put their findings into a useful form: a report, recommendations or a fact sheet, for example.

To anyone new to the idea, it’s bound to sound a little far-fetched. How can you trust a bunch of random people to understand a complex and disputed issue, have robust conversations about it, and then come to a consensus on how to address it? The exercise could be valuable in some way but to give them any form of authority or legislative power could be dangerous. But citizens’ assemblies are not entirely unprecedented. Indeed, it’s the legal system that first saw the decision-making value of people selected by lottery.

“It seems crazy to add a randomly selected group of people to the political process, right?” queries Levy. “But 800 years ago, it would have seemed crazy to have a randomly selected group of people to make decisions on someone’s guilt in a criminal trial.” Walker also sees the parallels between citizens’ assemblies and criminal trial juries. “Most [of the time] we will never know whether someone is truly guilty or innocent. We weren’t there; we don’t have the information. What’s important is there is a trusted mechanism where something emerges, and we say: ‘that’s fair enough’.

“With most public policy there is no one right answer. There is simply the answer the community views as fair.”

As simple as the concept might be, the practical reality of running effective citizens’ assemblies is anything but. Organisations like NDF and DemocracyCo have, over many years of implementing them, developed a deep understanding of the science-come-art.

Recruitment

NDF has landed on the golden number of 43 citizens through trial and error. It’s about balancing the need for a citizens’ assembly to be representative and for it to have the correct incentives to learn. With fewer than 25 people, you start to sacrifice diversity. With over 50, you compromise each member’s ability and desire to engage with the proceedings. The nuclear waste citizens’ jury struggled with this. With 350 people, group dialogue and cohesion was compromised. In hindsight, NDF thinks a better approach would have been to host several separate juries of 40-50 people, convening at the end of the process to find consensus.

And it’s not pure lottery; it’s a random stratified selection. In other words, a random draw that is matched to the census profile. With a wry grin, Walker tells me that if you don’t stratify, you get a room that is 80 per cent men over the age of 65. Since participating in a citizens’ assembly is entirely voluntary, there is a natural self-selection tending towards those with time on their hands and a bone to pick. It’s critical the recruitment process is controlled to make sure the people who are selected resemble the population they are representing. Otherwise, the process would lose its democratic legitimacy. Age, gender, location and income are common representative factors, but this can be a challenge in and of itself. Accurate data is hard to come by, and volunteers can be cagey when asked for information they see as sensitive.

In 2019/20, France’s Citizen’s Convention for Climate (CCC) brought together 150 citizens, who were split into sub-groups, to make legislative proposals for reducing carbon emissions. Producing 149 proposals, including draft legislation, over 16 days of deliberation, the CCC exhibited remarkable levels of consensus, with few proposals garnering below 70 per cent support.

Sonia Randhawa is an expert in recruiting for citizens’ assemblies. She leads the Australian branch of the Sortition Foundation, a not-for-profit social enterprise, which organises democratic lotteries for citizens’ assemblies around the world. It has developed open-source software to support transparent, random stratified selection which many implementers, including NDF, use. Since 2019, Randhawa has run over 50 recruitment processes as well as education campaigns on deliberative democracy but, she tells me, there’s plenty more work to do. “We’re constantly doing more research, we’re refining the software, we’re working to try to get higher response rates.”

To expect a response rate of anything more than five per cent is unrealistic and, usually, recruiters get closer to 2 per cent. The problem is particularly acute for people between the ages of 18 and 24. Once people have been recruited, it’s also a challenge to retain them throughout the process. Citizens’ assemblies are usually held on weekends to account for peoples’ work lives and the prospect of giving up a month or more of precious leisure time is a tough sell. At a recent conference hosted by Citizen Assemblies for South Australia, it was proposed that the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) be amended to give employees ‘democracy days’: leave entitlements like that given for employees selected for jury duty. “Remuneration is really important to ensuring diversity. Without it, you only get retirees and rich people,” says Randhawa.

Yet, she sees a deeper reason for the low response rates. “It’s a lack of democratic confidence. It’s thinking: ‘well, my voice doesn’t count’. It reflects the way in which we construct what politics is conceptually. Politics is seen as a specialised field and, yeah, I get to vote, but that’s about it.” For many deliberative democrats, it’s a catch-22. Citizens’ assemblies are a way of enhancing that democratic confidence but the cultural and economic hegemony of the elite over politics is strong enough that many lay people won’t, or simply can’t, sign up. Remuneration is one solution and making citizens’ assemblies compulsory, like jury duty, is another.

Designing the process

Now we come to crux of the process: how do you design a process to enhance deliberation? How do you balance procedural integrity and effectiveness? If the intention of deliberation is to exclude partisanship and interest groups, how do you stop them from creeping in?

One of the biggest hurdles at this stage is setting the agenda. As is the case with parliamentary inquiries and public consultations, partisan interests can frame the terms of reference and exert an overarching influence over the process. It means citizens’ assemblies can be manipulated and used to ‘rubber-stamp’ policies using narrow criteria. Emma Fletcher and Emily Jenke have been dealing with this problem over the decade since they co-founded DemocracyCo, another citizens’ assembly implementer like NDF. In the midst of the Albanese government’s Economic Reform Roundtable, I asked them how they would design such a process.

“The first thing we would do is make sure the question that we were deliberating on was the right question for the policy problem,” says Jenke. “Because, if you have the wrong question, then you end up in a really difficult position,” interposes Fletcher. “People will say: ‘well, that’s not really the conversation we need to have’.” Together, Fletcher and Jenke make a formidable duo. Fletcher specialises in the stakeholder engagement side of things, while Jenke is an effective and experienced facilitator. After a decade of working in the deliberative space, they’ve seen agenda-setting go wrong many times. They highlight the nuclear waste jury as a prime example. “Whether South Australia should store and dispose international nuclear waste was the wrong question,” claims Fletcher, “the right question was: what’s the best economic future for the State?” The difference between those two questions is vast. It demonstrates just how much a citizens’ assembly can be constrained by narrowing its scope or embedding assumptions in the question it is asked. When I ask Fletcher and Jenke how often political interests try to meddle with the agenda, they are honest. “Constantly,” bemoans Fletcher. “It’s a regular thing,” acknowledges Jenke, “I think we can safely say that any client that works with us has an agenda, right? We’re asking them to set their agenda aside and trust the process.”

For Walker, the solution to this problem, which also applies to the learning process, is to double down on the people power. NDF aims to give the citizens’ assembly the autonomy to set its own questions and to call its own experts. “We ask citizens what do you need to know and who do you trust to inform you? That gives them control of the content and the sources,” says Walker. This, he contends, prevents political framing and empowers participants to explore contested issues freely. It allows the process to remain independent, responsive and genuinely deliberative.

But, throughout the process of speaking with a number of experienced implementers, one design element comes up again and again as the most important for effective deliberation: time. In citizens’ assemblies, participants are asked to grapple with complex, emotionally charged issues—often with no prior expertise. Without adequate time, the process risks replicating the superficiality of conventional politics. Deliberation requires space to absorb evidence, reflect, question assumptions and engage with competing perspectives. It’s not just about reaching a decision, but about how that decision is reached. Assemblies that are hurried or under-resourced risk eroding their legitimacy. When given time, citizens can move beyond instinct and ideology, toward reasoned consensus. In many ways, it’s a democratic analogue to due process—where time is not a luxury, but a safeguard of integrity.

Around the world

Believe it or not, Australia was once seen as a world leader in pioneering citizens’ assemblies as deliberative mechanisms. In fact, if you look at the raw numbers, Australia still seems to be leading. However, in the last decade or so, other countries have overtaken Australia by prioritising quality over quantity. I spoke to John Dryzek, one of the world’s leading deliberative scholars, about this. “The problem in Australia,” he says, “is that all [citizens’ assemblies] have happened at state and local levels. There’s been almost no uptake of these ideas at the federal level.”

Meanwhile, in places like Canada, Ireland, France and Belgium, citizens’ assemblies are being held at the national level on the biggest issues of our time. In 2019/20, France’s Citizen’s Convention for Climate (CCC) brought together 150 citizens, who were split into sub-groups, to make legislative proposals for reducing carbon emissions. Producing 149 proposals, including draft legislation, over 16 days of deliberation, the CCC exhibited remarkable levels of consensus, with few proposals garnering below 70 per cent support. While the French Parliament ultimately passed legislation enacting the proposals, controversy over the degree to which it reflected the will of the CCC overshadowed this achievement.

Belgium’s Ostbelgien model is unique: in 2019, it institutionalised a permanent citizens’ council that sets agendas and selects participants for rotating citizens’ assemblies. That’s right, they have a citizens’ assembly that is legislatively empowered to submit its proposals directly to Parliament. While this has led to impactful reform on healthcare and affordable housing, many see the ongoing feedback loop between Parliament and people, which fosters a perpetual dialogue, as the major success.

Perhaps the most remarkable example of the use of citizens’ assemblies to address contested, divisive issues is Ireland. In 2016, An Tionól Saoránach (in English, simply ‘the Citizens’ Assembly’) was established to consider particular political issues. The first it was tasked to tackle? The constitutionally entrenched right to life of an unborn foetus. Over the course of five weekends across five months, 99 citizens consulted two obstetricians, two constitutional lawyers and a medical lawyer, as well as individuals sharing personal testimonies. When it came to a vote, there was strong consensus for constitutional change (87 per cent) and majority support for a constitutional head of power for Parliament to make laws on the matter (57 per cent). While the outcome did not immediately lead to a referendum, one along the lines of the Citizens’ Assembly proposal was eventually held in 2018. It was successful, garnering 66.4 per cent approval. Voter turnout was the highest in Ireland’s history and a majority of all regions, genders and age groups (except 65 and over) voted yes.

These examples show that, when citizens’ assemblies are well-designed and supported by legal frameworks, they can foster unity and influence policy. It also shows that they can pave the way for successful constitutional reform, something that has not happened in Australia since 1977. However, their impact depends on political will and whether governments treat their recommendations as binding or merely consultative. As Dryzek puts it, “We have to think long and hard about how these sorts of processes fit in with the existing dominant institutions of government. Sometimes they challenge, sometimes they support, sometimes they’re connected with dominant institutions. So, it’s really important to think of that landscape as a whole.”

Transformative power

There’s another, more intrinsic value in citizens’ assemblies. Not only do they have the potential to revolutionise law and policy making—they transform the people involved. Participants consistently report increased levels of political engagement, democratic confidence and a deeper understanding of complex issues in their society. The process of learning, deliberating and reaching consensus fosters civic agency and a sense of ownership over public decisions.

This year, after running a citizens’ assembly on offshore wind power, DemocracyCo collected pre and post poll data on social licence, cohesion and community, and democratic skills. The results were remarkable. Not only was there a 30 per cent increase in support for offshore wind, there was a 102 per cent increase in participants agreeing they knew a lot about the subject matter. Moreover, all participants felt they had a better understanding of competing perspectives and that the process enabled them to have civil and respectful conversations. Data from France’s CCC shows that many participants went on to vote more regularly, engage in community initiatives and advocate for democratic reform. Thirteen participants went on to launch political careers. Talk about an awakening.

The experience of being heard, respected and empowered to influence real decisions counters the alienation many feel in representative systems. Authentic deliberation cultivates empathy and reduces polarisation—participants learn to listen actively, and reconsider deeply held assumptions. It is a reminder that there is an inherently relational element to the normative power of law. When people feel part of the process, they are more likely to respect and uphold its outcomes. Citizens’ assemblies offer not just better decisions, but better citizens themselves.

Through respectful, inclusive dialogue and exposure to diverse perspectives, citizens’ assemblies foster democratic confidence. They model a form of discourse that counters polarisation, encouraging broader civic participation and thoughtful engagement across our increasingly divided society.

The future

There is an immense spectrum of possibility when it comes to citizens’ assemblies and deliberative democracy more broadly. Ironically, amongst deliberative democrats there isn’t much consensus on what the ideal deliberative democracy looks like. Some, like Dryzek, see it as an aspiration for whole systems of government. Likewise, Levy envisages a ‘Peoples’ House’ that is constantly reconstituted as the second House of Parliament, but concedes this is probably more realistic in systems with a single legislative chamber. Others are more wary of leaping to institutionalisation, fearing this brings citizens’ assemblies too close to the vices of conventional politics. For Walker, the next big step is to establish an Office of Deliberation that is attached to the Prime Minister’s office and tasked to deliver two citizens’ assemblies per term of government. Jenke has a similar idea but doesn’t want to limit it to just the Prime Minister; every Member of Parliament should deliver one in their electorate per term.

Visions of a paradigm shift underpin all of these ideas. Through respectful, inclusive dialogue and exposure to diverse perspectives, citizens’ assemblies foster democratic confidence. They model a form of discourse that counters polarisation, encouraging broader civic participation and thoughtful engagement across our increasingly divided society. They have the potential to transform our political culture from the ground up; to evolve our polity into one that understands itself and is willing to listen and change.

Most importantly, citizens’ assemblies remind us that law draws its strength not from force, but from consent—and in doing so, they may yet recapture the normative power of law. Whatever the deliberative utopia may be, one thing is clear: there is an immediate and desperate need for authentic deliberation in Australia and throughout the democratic world. As democracy trembles over an eroding rule of law, citizens’ assemblies may offer a silver bullet. We just need to have the courage to load the chamber.