Solicitors have to understand the technology in the sector really well, and that understanding fundamentally needs to change, at least every quarter, but feels like every week. Who was talking about ChatGPT before January when it started making headlines?

As the spotlight narrows on the way companies use and store personal data, the heat is turning up on organisations to provide greater transparency about their practices. As the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) investigates the way tech giants control our information, solicitors in NSW are calling for greater education about the ability for data to stronghold the future of the profession.

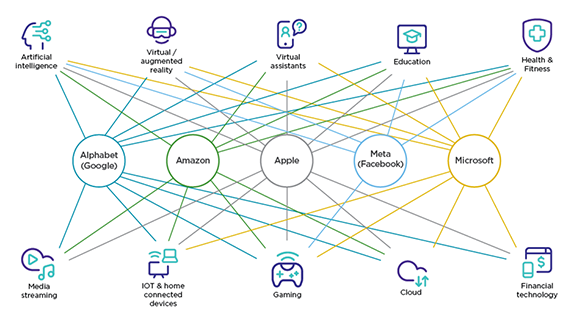

Australia’s consumer watchdog has launched an investigation into the way major tech companies like Amazon, Apple and Google are not only using data from smart devices, but how they are expanding their reach into home assistance products, cloud storage, and AI chatbots.

In March, ACCC chairwoman Gina Cass-Gottlieb, previously a partner at Gilbert + Tobin for 27 years, announced that the Commission would examine the “expanding ecosystems” of digital platform service providers in Australia as part of its ongoing regulation in this space.

“Large digital platforms have become an integral part of our daily lives, they have access to enormous user databases and personal information across their ecosystems,” Cass-Gottlieb said.

“This report will assess how that data can be leveraged across products and services within an ecosystem that may prevent businesses from entering and competing.

“Interconnected products, like smart home devices and cloud storage solutions, can provide consumers with a seamless experience that simplifies everyday tasks, but it’s important that competition and consumers are not harmed as digital platforms invest across different sectors and technologies and expand their reach.”

This review feeds into the ACCC’s five-year inquiry into digital markets, following a direction from the Federal Treasurer in 2020 requiring the body to provide reports every six months.

The Commission has published an issues paper that seeks submissions from consumers, businesses, and stakeholders about the “investment decisions” made by tech companies, including the “interconnectedness” of expanded products and services, and the potential impacts on competition in the space.

UNSW Business School’s Professor of Practice and Principal of Data Synergies Peter Leonard

UNSW Business School’s Professor of Practice and Principal of Data Synergies Peter Leonard

Agency over data

According to research detailed in the issues paper, the five largest tech companies – Google, Apple, Amazon, Meta and Microsoft – had collectively acquired 825 companies between 1987 and 2023.

The review is also considering how data collected by smart home devices and voice assistants, such as Amazon’s Alexa or Google Nest, can be used for other purposes. And most notably, the Commission is asking to what extent consumers understand the way their data is being used.

Further, the Commission will probe cloud storage platforms like Apple’s iCloud, and how difficult it is for people to migrate their data if they switch providers. “Excessive collection and potentially problematic” use of personal data or other behaviours such as dark patterns to confuse or manipulate consumers will also be considered.

UNSW Business School’s Professor of Practice and Principal of Data Synergies Peter Leonard told LSJ that the major tech companies are “leveraging” off their established data ecosystems when it comes to vying for consumer attention, giving them an unfair advantage in the market.

Leonard says therefore the ACCC is interested in further regulation, as it goes to bigger issues around privacy, knowledge and how much agency these companies give users over the control of the data.

“There is a lot of interest and disquiet of individuals, as to how and when and whether information is being collected by devices. It manifests in a variety of ways,” Leonard says.

“Firstly, you see people complaining on social media that Alexa, for example, must be spying on them because one minute they were talking about a holiday in Cairns with their partner and the next time they are online, they are presented with flight options.

“The other example is in the case of an Airbnb that might have cameras or voice recording devices. The issue is there is a complete lack of transparency and a lack of agency as to whether an individual can know what information is being collected about them, and further to be able to exercise any degree of control over that.

“It’s not like when you set up your mobile phone and you select options around sharing tracking information or location services. With the Airbnb example, you simply don’t know what data is being collected because you aren’t involved with the making of those settings.”

Morgan Lane, corporate technology lawyer at Colin Biggers & Paisley, speaks with LSJ via Zoom from the company’s Melbourne office and notes how data and cyber security are permeating public conversation, particularly in the wake of the major data breaches on Optus and Medibank in 2022. Lane runs cyber security seminars, providing background and information to solicitors on breaches.

Although he does not represent “big data” or multi-national corporations, Lane does represent many SMEs and start-ups who engage with the “big players”, and thus sees the potential impact of the ACCC review on his clients.

“I have a client who is in AI and at the vanguard of developing very relevant and practical software. However, when they deal with large data companies, it is very much ‘this is the world, and how you have to deal with it’. And what you find is, businesses working with the large data companies (such as my clients) have to live with certain Australian consumer law provisions, and risk allocation. Whereas, who they are dealing with upstream, big data, well big data doesn’t necessarily feel that brunt,” Lane explains.

“The ACCC is interested because the moment you get homogenisation, or centralisation of technology, competition drops off. Slowly you get to a place that is anti-competitive.

“The biggest tech firms have become the decision makers, employers and lobbyists. It is a movement away from a larger more diverse ecosystem to a centralisation of thought, and supply of goods and services.

“There is a lot of good that comes out of it, and I don’t think anyone wants to go back. But there is a valid role for having a look at this space.”

Morgan Lane, Partner at Colin Biggers & Paisley

Morgan Lane, Partner at Colin Biggers & Paisley

People are so involved in their lives, their clients, and running a practice that the practice management side of data security becomes too overwhelming like ‘where do I start and where does it end?’

Education for solicitors

Leonard and Lane agree this is a burgeoning space for solicitors in Australia and say education about technology and data should be a staple piece of ongoing training, regardless of practice area.

Leonard says for lawyers to grasp the issues in the ACCC report alone, they first need to understand technology and how data moves around in platforms, which is constantly changing and progressing.

“Solicitors have to understand the technology in the sector really well, and that understanding fundamentally needs to change, at least every quarter, but feels like every week. Who was talking about ChatGPT before January when it started making headlines?” Leonard says.

“They need to be looking at which legal systems apply and how they interact. Asking questions like to what extent does data privacy law adequately regulate the sector? And to what extent is Australian consumer law relevant? That is even before you start talking about proposals for AI regulation and what that should look like. Then intellectual property law comes in too.

“The key point is that it is a very complex area to deal with.”

Lane added that a technology-based or security-based CLE (continue legal education) course should be implemented as a mandatory way to educate the profession.

“All the solicitors in NSW have different skill sets and are from different areas and age groups. An education piece on this should be part of our ongoing training, in the same way we do Ethics every year,” Lane says.

“People are so involved in their lives, their clients, and running a practice that the practice management side of data security becomes too overwhelming like ‘where do I start and where does it end?’

“There is no legal benchmark for data security. When it comes to dealing with big data, and your practice, maybe it would be helpful to have some pointers about risks with dealing with big data.

“I was talking to a junior lawyer the other day about TikTok. It is about realising what we are dealing with there and being able to make informed choices about how to conduct your practice, knowing the challenges you face, but also keeping in mind what your clients are expecting.”