Jonathan Biggins, the co-creator and star of Sydney Theatre Company’s The Wharf Revue returns for a final campaign playing former Prime Minister Paul Keating in The Gospel According to Paul. He reveals the surprising audiences and unexpected delights of assuming the role.

In the current political landscape (not just Australia but globally), how does it feel to portray someone so renowned for their rhetoric and boldness?

It’s an honour and a privilege. The success of the show hinges upon not only Keating’s impressive story but also his theatricality, his ability to throw the switch to vaudeville and dance above his adversaries, throwing bombs with as much panache as he could manage. In his view, leadership is about two things: imagination and courage, and he used all the skills at his disposal to radically reform Australia’s economy and its self-image of where it belonged in a changing world. But above all, everything he did was motivated by his inner life, his belief in the ideals of the Enlightenment and the pursuit of perfection – even though you know it doesn’t truly exist, one should always strive towards that still place with the long straight lines of logic. He once said: “I know there’s no such thing as the ideal, but it’s a reasonable guide to what you should be doing.” Not so sure that there’s a lot of that sort of philosophical reflection in Canberra today.

Does the show take on any particular resonance now that there are (almost) wall-to-wall Labor governments across Australia?

I don’t think so, partly because you’d be hard pressed to know they were Labor governments in the traditional sense of the word. But in defence of modern politicians, they operate in a very different landscape to the one Keating dominated. He didn’t have the relentlessness of the 24 hour news cycle, social media and it corrosive influence on public discourse, identity politics which, although well-intentioned, views everything through a prism of self-interest, or the scorched-earth policy of contemporary oppositions who don’t seem to realise that if they tear everything down, what is left for them to inherit? Perhaps the show resonates for so many people because it’s a stark reminder of what we’re now missing.

Are there any current leaders who you would ever consider portraying next?

I’ve done Albo [current Prime Minister Anthony Albanese] in the recent Wharf Revues and despite looking nothing like him, people are convinced I’m the spitting image. The tricks of impersonation! But much as I enjoy playing him in the sketch format, I don’t think he’d hold for ninety minutes. Nor any of them really. Gough [Whitlam] would have been fun 30 years ago but I think the audience might be dwindling. Having said that, a lot of Keating’s fans weren’t even born when he was Prime Minister.

Has any audience reaction to the show in the past ever surprised (or particularly delighted) you?

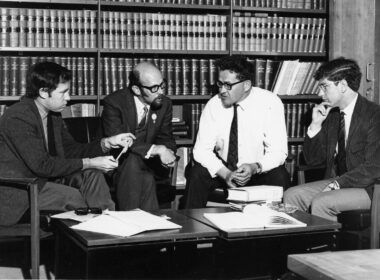

What does surprise me is that even though the general public are probably equally divided in their love or dislike of Keating, they all have respect for him (even if grudging). I played the show to sell-out houses at the Glen Street theatre in the heart of [Tony] Abbott’s old electorate and I’m pretty sure only about three of them had ever voted for the ALP in their lifetimes. And then there were many of Keating’s colleagues who’d come along, people like John Dawkins, Gareth Evans, Don Watson, Barry Jones. I did feel slightly alarmed when one of Keating’s daughters and [Keating’s former wife] Anita approached in the foyer after the show. Unsurprisingly, she was very gracious.

What can someone coming to the show for the first time expect?

A reminder of what political leadership actually looks like. The fascinating story of an autodidact who left school at fourteen, spent three months’ wages on a French pocket-watch a year later then went on to become the then youngest person elected to parliament, the nation’s leader and a world authority on French antiques of that narrow window between Robespierre and Napoleon. And probably the funniest, sharpest Prime Minister we’ve ever had. What’s not to love? But overall, it’s an entertaining show that has laughs, history and heart.

What are the hardest and easiest parts of portraying Paul Keating?

It’s quite an effort sustaining 90 minutes on stage by yourself but the upside is the touring costs are lower. The easy part is the swagger, the public self-belief and the grasp of the broad sweep of history. Slightly harder is avoiding being hagiographic – how does one critique a character when the only person speaking is a character not given to self-criticism?

The Gospel According to Paul runs at the Sydney Opera House from 4-23 June.