Snapshot

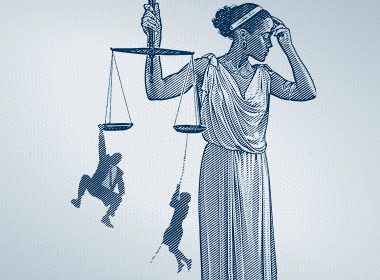

- The Minister for Immigration owed a duty of care to a refugee at Papua New Guinea by reason of the salient features listed in Stavar: coherence, policy, vulnerability, reliance, control and assumption of responsibility.

- Having regard to the Shirt factors, the Minister failed to exercise reasonable care to discharge the responsibility he had assumed to procure a safe and lawful abortion for her.

- The judgment emboldens claims of negligence against Australia for breaching a duty of care owed to asylum seekers on Nauru.

In Plaintiff S99/2016 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2016] FCA 483, Bromberg J applied orthodox concepts of the law of negligence to conclude that the Minister of Immigration had breached a duty of care to procure a safe and lawful abortion for a refugee raped while awaiting resettlement at Nauru and transferred by Australia to Papua New Guinea (PNG). This article identifies some implications, but first recounts the facts.

Background

Plaintiff S99, a young African woman, arrived in Australia during 2013 by boat from Indonesia. She was designated an unlawful non-citizen and transferred to the Republic of Nauru where she was detained until 2014. She was recognised as a refugee, released from detention and awaited resettlement. In 2016, she suffered a seizure likely to have been caused by epilepsy and was raped while unconscious. She became pregnant and required an abortion. For that purpose she needed medical resources including specialised expertise and equipment because of her neurological condition, poor mental health and other physical and psychological complications.

The Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (the Minister) accepted that Plaintiff S99 could not procure an abortion without his assistance. But he refused to bring her to Australia. Departmental policy sought to ensure that irregular maritime arrivals like her were treated for medical support in a third country outside Australia and she did not fall within the allowance made for ‘exceptional circumstances’ (at [395]-[396]). The Minister instead took her to Port Moresby.

Plaintiff S99 claimed that an abortion in PNG would be unsafe (because a lack of medical resources exposed her to grave risks) and illegal. She asserted that the Minister had a duty of care to procure a safe and lawful abortion for her, and it need not be conducted in Australia.

The Minister denied that such a duty of care existed. If it did, then there was no breach because the standard of care must be assessed by reference to the medical services reasonably available in PNG.