What are the intellectual property and copyright implications when robots use existing art to generate their 'own' work? How does Australian law on this compare with international law?

From ChatGPT making headlines, to artificial intelligence tools threatening to outperform human artists, the AI-generated content scene is a hotbed of activity. With the ability to create a unique piece of art in the style of the most recognised artists given to everybody, this is a major new frontier of the internet.

As impressive as it is to see the progress AI models have made in the past few months, it is important to remember that these models and their outputs are subject to existing laws and regulations, including copyright and intellectual property laws. There are deep concerns in the art industry, with many claiming that AI generators have been infringing on artists’ rights. This has resulted in a recent class action suit against Stability AI, Midjourney and DeviantArt brought in front of a US court by Karla Ortiz, Kelly Mckernan and Sarah Andersen. The plaintiffs allege that training the defendants’ AI models on images scraped from the web was a breach of copyright law. Many lawyers are holding their breath for the outcome.

These developments have raised a number of legal questions, which need to be answered: Are companies who own the AI models trained on the work of artists responsible for copyright infringement? Or is it the users of the models who are liable? How do we define infringement – and then enforce it? Do existing laws have sufficient core principles and flexibility to cater for AI legal issues? Can AI generator owners be charged with plagiarism? The legal uncertainties are daunting.

It will be interesting to see how such issues are addressed on a cross border basis and across civil and common law legal frameworks. Artists may have an easier time enforcing the copyright law against AI once there is a precedent in the common law jurisdictions, but what will they be left with if the precedent is not in their favour?

Hope for Australian artists?

Looking at the Australian legal framework, artists have cause to be hopeful. At present, there are no copyright exceptions in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 for artificial intelligence purposes, such as data scraping or using copyrighted work for machine learning. Moreover, the established definition of the copyright under Australian law favours human artists over AI, as in order for copyright to be established two components must be present: the work has to be original and it has to come from an author. Australian precedents have established that the author of a copyrighted work must be human. Two such rulings are the IceTV Pty Ltd v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd (2009) 239 CLR 458, where the High Court underlined that copyrighted works have to be produced by “an independent human intellectual effort”, and Telstra Corp Ltd v Phone Directories Co Pty Ltd [2010] FCAFC 149, where the Full Federal Court ruled that the copyright work must come from a human author.

‘The established definition of the copyright under Australian law favours human artists over AI, as in order for copyright to be established two components must be present: the work has to be original and it has to come from an author.’

In the case of civil law systems, under which more than half the countries in the world operate, are policymakers too late to step in? Writing comprehensive policies is a challenging and time-consuming task, and even if the laws changed immediately, many claim that much harm has been already done with existing breaches. Let us not forget one of the basic rules of law: Lex prospicit, non respicit (The law looks forward, not backward). However, while for some it may be too late, it is worth addressing the issue for the future of the artistic community, to prevent further damage.

Supporters of AI argue that using somebody else’s art to train an AI model falls within the ‘fair use’ doctrine. However, detractors hold that this type of art is generated for profit, and it can have significant negative economic impacts on the original copyright holder. They support their opinion by noting that AI does not transform the original work significantly and it does not create its own style. Looking at some examples on the internet, it is sometimes hard for the untrained eye to tell the difference between a piece generated by an AI and an original one.

One might argue that if artists decided to post their art online, and consented to terms and conditions (“T&Cs”) on platforms which do not prohibit AI models from collecting data from them, they do not have a strong defence. While this stance has validity, does a strict legal interpretation necessarily uphold the right moral position?

Online art platforms

Online art platforms such as ArtStation provide valuable exposure which art creators need to gain recognition. These platforms are the locations where artists build their brand and find potential customers, and they must accept the T&Cs to use the service. However, even if professional artists read the T&Cs before accepting (and who among us can claim to have vigilantly read the same?), this does not mean they have any actual power or ability to negotiate them. Who would they negotiate with, and how would they tailor those agreements to their specific needs?

It is also worth noting that such T&Cs – or lengthy “click to agree” conditions – were written (and accepted) by many artists before AI art generators presented a threat to the industry. It seems unreasonable to argue that artists should have predicted something that only a few months ago was unthinkable.

Many platforms such as ArtStation now give artists a choice about whether their art can be used by AI models. Nevertheless, the devil is, as always, in the detail. This protection is available to artists via an opt-out system – art needs to be tagged with a ‘NoAI’ tag for this to work. Many artists feel it should operate as opt-in system; a matter, again, of debate and subjectivity.

The moral, ethical, and legal concerns surrounding art generators are numerous, but it is important to raise the debate and work towards a consensus. We will not and should not stop technological development. However, we must also work towards an ethical future and make sure the technological developments result in a safer and better world. There are many ways AI art generators can benefit artists, individuals and businesses, but we must ensure the benefits do not outweigh the problems. Implementing restrictions on what type of art is generated, or moving to an opt-in system, could address some of the issues. Alternatively, the platforms providing legal contracts and remuneration for those whose art (with consent) is used could be a solution.

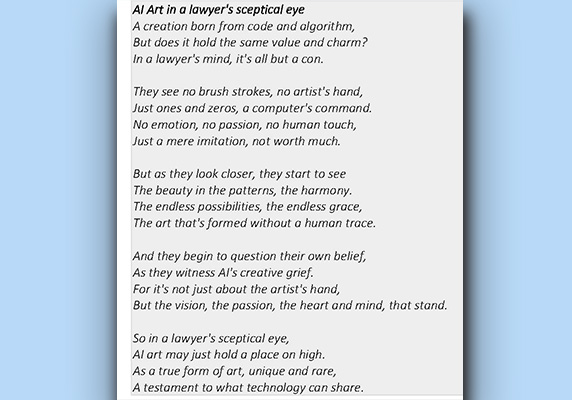

Lastly, inspired by an article written by Annan Boag, this author had no hesitation in putting ChatGPT through its paces. When asked to write a poem titled ‘AI Art in A Lawyer’s Sceptical Eye’, this is what it produced:

Ola Wesolowska is a legal consultant at D2 Legal Technology.