Sydney criminal defence lawyer Annette Gibson recently accepted an invitation to speak at the ANZAC Day Sandakan Memorial in Borneo about the life and service of her uncle Nelson, better known as Private Nelson Alfred Ernest Short, of the 18th Australian Infantry Battalion.

“My Uncle Nelson’s story is one of resilience and strength in adversity,” Gibson, the Principal Solicitor at Burwood Criminal Defence, told LSJ shortly before flying out.

“This is something that all legal practitioners should strive to achieve. Ours is a profession where empathy, problem solving and composure are important skills that can be achieved with experience, patience and, importantly, respect for your fellow practitioners – whether they be on ‘the other side’, your peers or the staff you manage.

“Striving for excellence is more important than striving for promotion and it shouldn’t be at the detriment of your fellow practitioner. Being positive, engaging in pro bono work and giving yourself time off are important in our profession.

“Whilst researching for my Ode to Remembrance speech, I reflected on my uncle’s strength and his will to survive, and I now draw on those qualities when the pressure mounts,” she says.

“It is often said that the way to honour the prisoners of Sandakan is to remember them, and the way that I try to remember Uncle Nelson and his comrades is to live and work in the way that they did, by striving to daily manifest the personal qualities of resilience and strength in adversity.”

Below is the speech delivered by Annette Gibson at the event:

My mother, Nancye Short, is the daughter of the late Edward Short, my grandfather. His brother was my Great Uncle Nelson, or Private Nelson Alfred Ernest Short, of the 18th Australian Infantry Battalion. He was one of only six men who survived 3½ years of torture, beatings, disease, malnutrition, and the infamous Death Marches from here to Ranau.

It is an understatement to say I am very proud and extremely honoured to be here on this Anzac Day in Sandakan, remembering my Great Uncle Nelson, as well as all those who lost their lives here. Private Nelson, or Uncle Nelson, as I knew him, was only 22 when he enlisted on 11 July 1940. Only 7 months later, after the fall of Singapore, he was a prisoner of the Japanese in Changi, and then transferred here, to the Sandakan POW camp.

At first the conditions weren’t too bad. Gradually, however, as rations decreased and some men escaped, brutality and murder became all too real for the prisoners. Uncle Nelson reflected on this, saying:

To think how you were going to survive, when you see the dead were living there, naked skeletons, ready to go out to be buried. Day after day, they were dying like flies in the camp, from malaria and malnutrition. And you thought to yourself, well, how could I possibly get out of a place like this?

As the Allied Forces advanced towards Borneo, the Japanese ordered the prisoners to march westward to Ranau. Weak and sick prisoners staggered along jungle tracks, heading towards Ranau, some 265 kilometres away. Uncle Nelson recalled that ‘When it came to the Death March, you thought, well, how could I possibly make it? I had never been a religious man, but I said my prayers through the march just to help me get through’.

Uncle Nelson told us that during the march, when a bloke couldn’t keep going you shook hands with them and wished them well, saying:

We knew and they knew what was going to happen, but you had to keep going yourself. It became increasingly obvious that the reason for the marches was to kill us all off one way or another so that there would be no witnesses to their atrocities. It was a case of be murdered, die of starvation or disease, or escape.

By some miracle, Uncle Nelson made it to the Ranau POW camp, where the conditions were horrific: no huts, food or medical supplies, and sleeping outside in all conditions. My Uncle, along with Andy Anderson, Keith Botterill and Bill Moxham, made the decision to escape. He recalled it was a dark night, pouring with torrential rain. The men stole as much rice as they could carry from the Japanese provisions hut, and took off into the pitch-black jungle.

Uncle Nelson described his thoughts at that time: How can I get out of this? And even after escaping, you say to yourself, well, right, we’ve escaped. Now what of our chances? We’re in the middle of Borneo, in the middle of the jungle. Sydney was a long way from there. How could we possibly ever survive? But we did.

Hiding in the jungle, the men sheltered in caves and abandoned huts. They must have been terrified when a Japanese soldier stumbled upon them, as they rested in a hut. Somehow the men convinced that soldier they had all contracted malaria, saying another Japanese soldier was off getting them medicine. Fortuitously, an Allied plane flew over, and the soldier ran for cover. Uncle Nelson said:

’When he ran, we ran’.

Uncle Nelson and the men were assisted by local people: ‘We ran into Baragah Katus, the bloke that found us’. Baragah said ‘Jepun. There’s Japanese round here’. We all remarked ‘Yeah!’ Baragah said ‘You come with me’. They found out later he was the head man of his local village.

I pause to acknowledge the selfless courage of Baragah Katus and all the civilians who helped my Uncle, and say Terima kasih banyak-banyak [Malay translated to English as “Thank you very much”]

Baragah built a little hut for them and left, but after a few days returned and said ‘Jepun getting close, you’ve got to go’. Anderson said ‘I’m too sick, I don’t think I’ll ever make it’, but he dragged himself to the next place. Whilst they rested inside a hut, Anderson lay outside. Uncle Nelson went to him and then said to the others: ‘Well … Andy’s gone, he’s dead’. The men made an improvised grave, laid him down and covered him over with stones and leaves.

Then Uncle Nelson and the other men became ill. He recalled thinking:

That’s it, Bye-Bye, Blackbird, I’m really gone. I was fading away. This must be how you die and this is the end, but I didn’t want to, you know. And I fought against it and somehow, I started to come good.

One member of Z Force, an Australian Special Forces Unit, was John ‘Lofty’ Hodges, who was parachuted into North Borneo on 18 July 1945, as news of escaped prisoners had reached Allied military headquarters. One of Baragah’s men came to Uncle Nelson, and told him men had landed nearby in parachutes. Baragah went off to investigate and returned later with a note and a parcel, containing amongst other things, a packet of Life Savers. The note said ‘The war is over’ but it also warned ‘Stop where you are because there are Japanese in the area ignoring the surrender and

[they] are hostile’. Uncle Nelson recalled ‘Well, we grabbed one another and loudly said ‘This is it!’. Moxham cautiously said: ‘Don’t sing out too loud, don’t get excited, you know, somebody might hear you’.

A week later, and worried the Japanese were nearby, the men continued on in the jungle, when they heard the tramping of heavy footsteps. The men were expecting the worst, when an undeniably Australian voice boomed: ‘How ya’ going, boys?’ Lofty Hodges later recalled he could scarcely credit that the bearded, ravaged, pathetic creatures staring at him, with a look of profound wonderment, had once been Australian soldiers. Uncle Nelson recalled:

“… and I’ll never forget this as long as I live – as we walked from the jungle to safety we could hear the rat-tat-tat of machine gun fire coming from the camp at Ranau, as the Japanese finished off the last poor devils from the Death March.”

Recalling how he got through this incredible, awful ordeal, Uncle Nelson said he would think about getting home and that:

You had to keep going yourself, you couldn’t do anything else. It was the survival of the fittest. It was just the will to live. To fight against it and to want to live. I never gave in. You’ve got to have will. And I think that’s what got me through, and I think that’s what got the other boys through, too.

I’ve searched for a word to describe my Uncle Nelson’s amazing good fortune. Was it determination, willpower, resolve, strength of character, or was it just very good luck to survive the greatest single atrocity committed against Australians during wartime? Whether it was luck, strong will, or a mixture of both, my Uncle Nelson, unlike the many who tragically died here, was fortunate to live a fairly long life, passing away in 1995, aged 77.

We come together on this Anzac Day to remember those many young lives that were tragically and horrifically taken in Borneo. We join our brothers and sisters in Gallipoli, at home in Australia, and around the world, to commemorate and honour all Australian, New Zealand and British service men and women.

Lest we forget.”

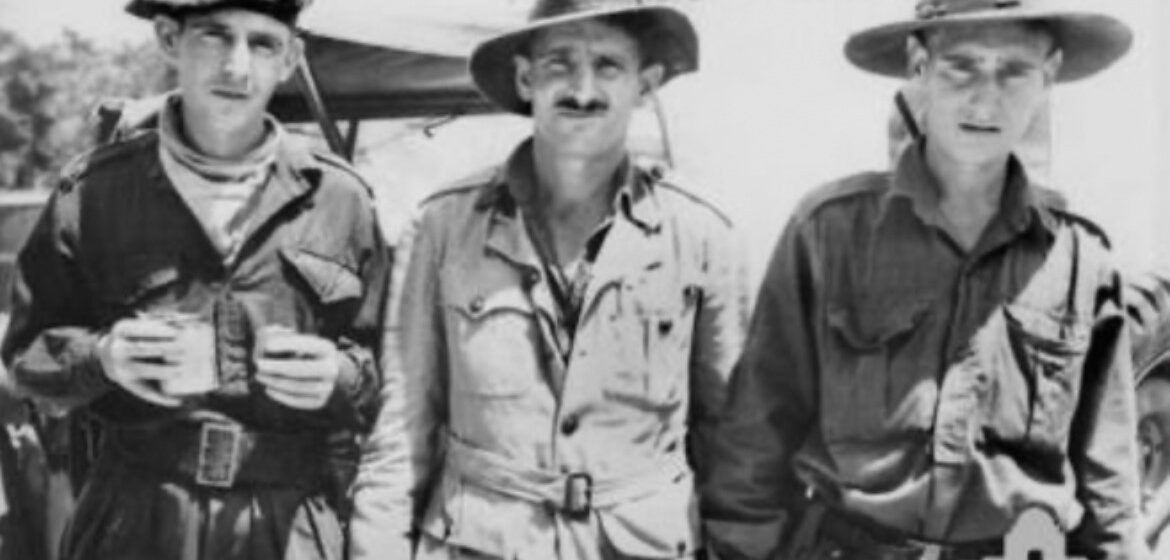

Header image: L to R – Privates Nelson Short, William H. Sticpewich and Keith Botterill