‘[The Voice] is such a modest proposal for the overwhelmingly positive outcomes it will have for the Australian people.’

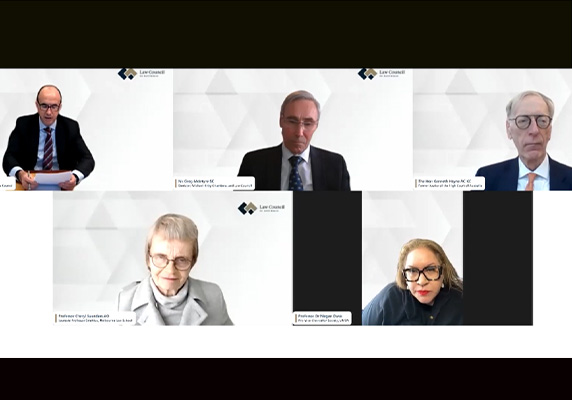

Ahead of the Referendum on the Voice on 14 October 2023, the Law Council of Australia held a webinar titled ‘The role and value of a constitutionally enshrined Voice’.

The webinar was intended to offer the Australian legal profession the opportunity to gain information and guidance on the origins, purpose, and constitutional implications of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice; it was also intended to articulate the basis of the Law Council’s support for the Voice.

Uniquely qualified

“The legal profession is uniquely qualified to assist the Australian community to understand this issue,” Law Council of Australia President Luke Murphy said. “We have a responsibility, as a profession, to help people fully understand what is being proposed.”

Murphy also acknowledged the difficulty, in the age of social media, to promote “a focused, robust public dialogue.”

“The webinar is one of several activities by the Law Council,” Murphy said, “to ensure that lawyers across Australia – and by extension their communities and networks – are accurately informed about the 2023 Referendum process and question, and able to help prevent the spread of misinformation.”

Interest in the webinar, open to legal practitioners across Australia, confirmed the desire of the legal profession to be better informed. Almost 600 people attended the live session, and registration included members of the legal profession from across all the states and territories, and from all areas of the legal sector: large law firms, smaller private firms, community law centres, academia, government, and civil society organisations, as well as a small number of barristers and judicial officers.

The aim for the webinar was to provide a forum through which the profession could directly engage with the Law Council on its position on the Voice. On 20 September 2023, the Law Council had issued this statement on its position:

In consultation with its Voice Referendum Working Group, Indigenous Legal Issues Committee and constituent bodies, the Law Council has closely considered the proposed constitutional amendment, the referendum question, and the referendum process more generally over the past year or so. The Law Council’s view is that the Constitutional amendment as proposed is constitutionally orthodox, just, and legally sound.”

Questions were called for ahead of the webinar, and the webinar was dedicated to responding to the main themes presented by the questions submitted.

The panellists were chosen for their legal expertise and experience, particularly in constitutional law and public law, their leadership on this issue and their standing within the profession. Equal gender representation and representation across the states and territories also played a part in panel selection.

“These speakers are some of the most esteemed legal minds in this country, particularly in Constitutional law,” said Murphy.

All panellists were members of the Law Council’s Voice Referendum Working Group, and two were also members of its longstanding Indigenous Legal Issues Committee. The panel members were Professor Megan Davis, the Hon Kenneth Hayne AC KC, Professor Cheryl Saunders AO, and Mr Greg McIntyre SC, and Law Council President Luke Murphy was the moderator.

For principle, not for meat on the bones

As the discussion began, Davis addressed the issue that has taken on a life of its own in public discourse about the Voice: the lack of detail in the wording.

Davis is Pro Vice-Chancellor Society (PVCS) at UNSW Sydney. She is also the Balnaves Chair of Constitutional Law, a Professor of Law, and Director of the Indigenous Law Centre, UNSW Law. She has been a leading lawyer on constitutional reform for the recognition of First Nations rights for two decades and has led the Uluru Statement from the Heart work for the past five years.

If the referendum is successful, Davis said, a new section 129 would be added to the Constitution, with the following wording:

129 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice

In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia:

(i) there shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice;

(ii) the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

(iii) the Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures.

“Constitutions are documents that don’t involve huge amounts of detail being included in the text. We say Constitutions are for Constitutional principle,” Davis said, “and the Parliament is for legislation, is for the meat on the bones, for the detail. If people want to know more, they should look at the site ulurustatement.org.

“The fundamental principle we are asking Australians to support is recognition of First Nations peoples, and the creation of an entity that will allow First Nations people to venture an opinion on the laws and policies that are made about their communities.”

Murphy said, “[The referendum proposal] reflects how Constitutional amendment should occur and has in the past, in that it asks the public to vote on a principle and leaves it to Parliament to implement the detail.”

If the majority say yes, Davis said, then the Parliament will set up a Bill “that everyone will have input into, that will finally become law that puts the meat on the bones of what the provision has set out.”

She added, “[The Voice] is such a modest proposal for the overwhelmingly positive outcomes it will have for the Australian people.”

Professor Megan Davis

Professor Megan Davis

Hayne is a former Justice of the High Court of Australia. He was a member of the Constitutional Expert Group, chaired by the Attorney-General, which provided legal support to the First Nations Referendum Working Group about constitutional matters relating to the proposed amendment and the referendum more generally.

“Once you decide that Constitutions are where principles are put, not machinery,” he said, “it is inevitably quite wrong and it would be entirely now misleading to say ah, I can tell you what Parliament will do [in the future]. That’s for Parliament to decide. So, the suggestion of more detail: a mirage.”

The things we want to protect

What should be included in the Constitution, in terms of the Voice?

Saunders is an expert in Australian and comparative public law, including comparative constitutional law. She is Laureate Professor Emeritus at Melbourne Law School and was a member of the Constitutional Expert Group, chaired by the Attorney-General, which provided legal support to the First Nations Referendum Working Group about constitutional matters relating to the proposed amendment and the referendum more generally.

Saunders said, “the proposed section 129 already has all the detail we want to protect it from too-ready amendment. So subsection (2) tells you what the Voice will do, who we will do it with, what it will do it about. Those are the things we want to protect.” The number of members, she said, and similar details, “are not the things we want to protect: that we know we’ll need to change over time, and those are left to the Parliament.”

To the question “will the Voice change our democratic form of government?”, Saunders responded with an emphatic “Not at all. The [proposed structure for the Voice] fits with our democratic structure extraordinarily well.

“The Voice provides a transparent public mechanism that … leaves final decisions to government and Parliament, but provides a mechanism to strengthen the way the democratic process works.”

On the question whether the drafting of section 129 is constitutionally safe, Hayne said, “The drafting is sound and my answer is an unequivocal, unqualified ‘Yes’.” The wording is very simple. It says what it means and it means what it says. That is its great strength.”

Kenneth Hayne

Kenneth Hayne

‘The wording is very simple. It says what it means and it means what it says. That is its great strength.’

The power of the Voice

Murphy highlighted a question that has come up throughout debate in the lead up to the referendum: how much power will the Voice have?

“As the wording of the proposed constitutional amendment makes very clear,” he said, “the Voice will only be able to make representations to Parliament and the Executive, just as bodies such as the Law Council do on a regular basis.”

Davis added, “There is no obligation on Parliament or the Executive to respond to representations [from the Voice]. Some say that’s too weak; others say it’s too strong. We say it meets the temperament of the Australian political and legal system.”

The Voice will not result in changes to legislation, Saunders said. “If the Voice is established, its authority, its discretion, is to make recommendations. They can’t do anything unless the Parliament, or the Executive, picks it up and decides to run with it.”

A mirage, an amorphous fear

On the question whether the representations of the Voice will be caught up in the courts, Hayne said this is an unrealistic prospect, “a mirage which is seen as an amorphous fear.”

He added, “Judicial review of Executive action is an ordinary, unremarkable function of the courts which happens every day.

“We have to recognise that you can get judicial review if, and only if, you have an arguable case, brought by a plaintiff who has sufficient standing.”

Section 129, he said, gives Parliament the powers to make laws about whether, when and how decision makers should take account of a representation by the Voice.

“The prospect of a wave of Executive decisions being reviewed is, in my view, a mirage. I do not agree that it will happen.”

McIntyre, a barrister, began in legal practice with the Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia in 1976, and later became Principal Legal Officer of the Aboriginal Legal Service of WA. The High Court cases he has had conduct of include the Mabo cases, Mabo v Queensland [No 1] and [No 2].

If someone did try for judicial review, he said, “it’s hard to imagine a plaintiff who would have that special interest, and they would have to point to a right which was being infringed. And then you would have to consider, who’s likely to have the resources to run this wave of litigation? Certainly not the least resourced peoples of our nation. So there are many reasons why there won’t be a wave of litigation.”

Greg McIntyre

Greg McIntyre

‘Who’s likely to have the resources to run a wave of litigation? Certainly not the least resourced peoples of our nation.’

Hayne noted: “Should judicial review of administrative action emerge as a problem, the Parliament can and should deal with the issue and enact a law under section 129(3).”

Davis pointed out that “there is no obligation on the state, to the Executive or Parliament, to respond to the representations made by First Nations peoples.”

A lawyers’ picnic?

The panel discussed the question whether the proposed Constitutional amendment is legally risky, and agreed that establishment of the Voice would not result in excessive litigation that will impact the functioning of government.

Hayne said, “I see no legal risk. I do not accept that there will be any lawyers’ picnic if the referendum is passed.

“The Voice has a power to speak. That’s all. Parliament or the Executive will decide what to do in response. The Voice has no power of veto. The proposed amendment does not change in any way any power of the Parliament or the Executive.

“It does not impose any obligation to consult.

“Legal risk? No. Lawyers’ picnic? No.”

Davis added, “Every [set of] terms of reference for the past 12 years has been about testing the suggested amendments for [legal and constitutional] risk. That’s what we’ve devoted our lives to for 12 years. We are a country of very smart lawyers. And lawyers, particularly across the political spectrum, have spent the past seven years trying to draft this in a way that would minimise risk.”

No impact on private property

The panel discussed the question whether the Voice will impact on property ownership, a common thread in many arguments opposing it.

“That fear was expressed in the aftermath of Mabo,” Murphy said, “and post the Apology. It seems to be that there are certain elements of the public that want to wave that around as a threat.”

“There is no legal concern at all,” McIntyre said. “The Voice’s power is quite limited and quite focused. It’s about representations, saying things to the Parliament and to the Executive. It will have absolutely no power to deal with land or impact anybody’s title.

“Our political system has been dealing with native title and land rights for the last 40-plus years. We’ve been dealing with it in a way which is highly controlled by law,” he added.

“Determinations have been made, and none of those determinations have ever impacted on the private property interests which were granted by the Crown to Australians, and there’s no reason to expect that the Voice or anything coming out of the Uluru Statement will have any impact of that kind.

“First Nations people are not asking for anything like that. And it’s certainly something that the government and the Parliament have control over, in any event. The Native Title Act made it quite clear what impact Native Title would have on private property interests, and it’s none. The Voice will not take away anything from the 97 per cent of the population who are non-Indigenous.”

‘The Voice will not take away anything from the 97 per cent of the population who are non-Indigenous’

We know our people support it

The panel addressed the question of whether the Voice has the support of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Davis said the perception that many Aboriginal people do not support the Voice is as a result of “mainstream media [which] has elevated the No voices to the same level as Yes.”

“My comments are based on research and data. We know our people support it,” she said, citing extensive consultation over 12 years and three recent polls showing, respectively, 82, 83 and 87 per cent support for the Voice by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

“Sovereignty will not be ceded if the referendum succeeds,” Davis said. “To First Nations people who ask about this, the easiest answer is, no one can cede your sovereignty except you.”

McIntyre added, “Sovereignty is not being ceded by any change to the Constitution, which is by its essence a document of the colonising body, and the referendum vote will be by the whole of the Australian population, not by First Nations people per se agreeing to anything in particular.”

We lose nothing but gain so much

Haynes said, “The Uluru Statement asked us to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first people of Australia by providing in our Constitution that they may speak to Parliament and the Executive. That’s all this amendment does. By recognising our First Peoples in our Constitution in this way, we lose nothing, but we gain so much for the whole nation.”

Davis said, “It’s a safe and modest proposal. I can’t see any negative consequences of this for the nation. I can only see positive consequences in that it will bring unity and a greater sense of belonging to the country.

“And for the first time since 1788 we have spoken to, formally, the original grievance that our people carry in their hearts and in their health. It is such a modest proposal for such overwhelming outcomes that this will have for the Australian people.”

“Law reform is about imagination,” Davis said. “You have to imagine what the world can be, to make it a better place.”

A special role

Saunders said, “Our First Peoples are a very important part of our national identity. And this is a way to make them part of our Constitutional identity in a very streamlined, straightforward way that fits our system of government extraordinarily well. And lawyers have a special role to play in this. Lawyers understand text. Lawyers understand how legal text is likely to be interpreted. We have responsibilities.”

Professor Cheryl Saunders

Professor Cheryl Saunders

‘Lawyers understand how legal text is likely to be interpreted. We have responsibilities’

Murphy added, “We’re not advocating that people must vote one way, it’s a need to make an informed decision, and one that is properly informed and aware of what is being considered here.”

Murphy’s advice echoes that of Yindjibarndi woman Jody Broun, CEO of the National Indigenous Australians Agency. At a NAIDOC Week event at the Law Society of NSW, she urged lawyers to take two actions: to become fully informed about the Voice, and to share that knowledge with their connections.

Murphy encouraged attendees to access and share the Law Council’s Guide for the Legal Profession and fact sheet series about the Voice.

____________________________________

Also see LSJ explains the Voice referendum.

Wtch the full webinar here