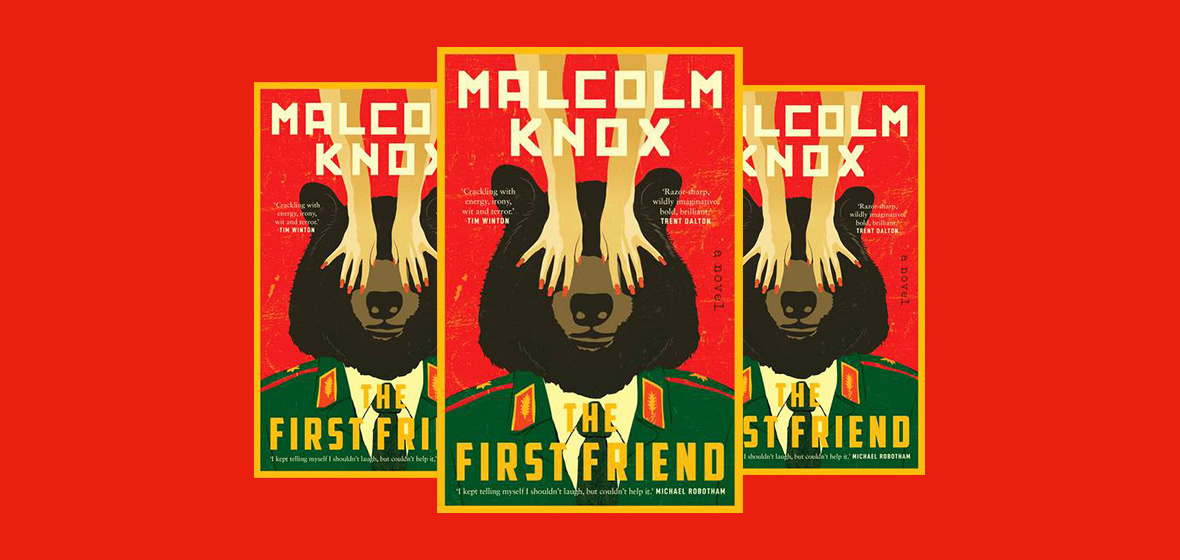

Author: Malcolm Knox

Publisher: Allen and Unwin

What makes psychopathic, murderous despots tick? That archetype – full of amusing insecurities and absurdities but apathetically bent on domination – survives and thrives today, whether amongst the political elite, everyday workplaces or even families. What can we do to resist them without becoming like them? Armed with Aussie wit, Malcolm Knox explores these questions and satirises the bullies in The First Friend, his seventh novel.

This time, he takes us to 1938 Soviet Georgia, an upside-down world of alternative facts, corruption and mass murder led by Lavrentiy Beria with Vasil Murtov, his right-hand man and supposed best friend, by his side. It’s an intense story, full of the violence and cruelty typical of that time. It’s also a scathing parody of Beria in a dryly sarcastic Australian voice. On the surface, it’s an absurd comedy that highlights the fragility and loneliness of people like Putin, Murdoch or Trump – though you’re more likely to shudder than laugh. But underneath, it’s a playful comment on the legacy of human monsters. For all their efforts to control their past, present, and future, it’s us regular people – like Knox, you, and I – who are writing and speaking their histories. And, of course, we’re going to have a little fun with it.

At the centre of The First Friend is Beria, a true historical figure, and Murtov, a fictional everyday man. Widely regarded as Stalin’s Himmler, Beria, a savant in mass extermination and known to be a serial rapist, was the leader of the Georgian Republic during the Great Purge. Murtov is his adopted brother and an ordinary, moral man with two daughters and an intellectual wife, Babilina. Stalin is coming to town, and the plot follows Beria and Murtov’s crazed preparations. Accordingly, The First Friend starts slow but gradually picks itself up to a frenzied finish as the big boss gets closer and closer. It’s a classic tale of Soviet intrigue where it’s every bureaucrat for themselves in a game of survival of the craftiest. The usual tropes subsist: surveillance, doublespeak and the ubiquity of death, to name a few. Post Death of Stalin, this falls a little flat, and despite the Australianisms, Knox struggles to bring something new to this type of satire. Foregoing psychological depth for absurdist humour, there are moments of truth in a sea of stereotypes and hyperbole.

However, the focal relationship between Beria and Murtov kept me going. Beria is a genocidal psychopath, and Murtov seems to be an ordinary guy who loves his family. As the scale of Beria’s evil and the detail of their shared history reveals itself, so too does the true question of this novel: why does Murtov, apparently loving and principled, abide his servitude and complicity to such a monster? What on earth motivates him to work so hard for this man? The answer is, of course, for you to decide. To me, there’s a clue to Murtov’s role in composing Stalin’s false histories for Beria. He is a faux historian but a historian nonetheless, and Murtov’s climactic act is to assert this power over Beria. He will ultimately determine how Beria is remembered long after they are both dead. Indeed, Knox is doing the very same. He makes his own distinct embellishments for Beria’s story in a way that reveals and humiliates Beria. Knox reclaims the blur of fact, fiction, history, and propaganda for the little guy rather than the monster. In this sense, he breaks a different sort of fourth wall, giving the reader a taste of their vulnerability to the storyteller of this official account, as benign and satiric as he may be. The result is a novel that is ultimately uplifting and will make you think about the nature of history and legacy: powerful yet slippery; tools for oppression but also counteraction; constantly shifting, never truly dominated.