As the profession strives for equity and equality, two ideas provoking debate are pay transparency and quotas for leadership positions. Could these lead towards more gender-equal workplaces?

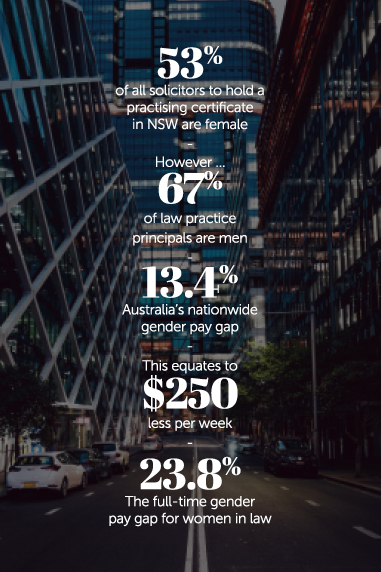

The law has a gender equality problem. For decades, women have entered the profession in Australia in equal or greater numbers to their male counterparts. According to the Law Society of NSW’s latest statistics, 53 per cent of all solicitors to hold a practising certificate in NSW were female.

Yet women remain starkly underrepresented at senior levels. As much is clear from the same data: of the 9,504 solicitors in the state to be law practice principals, 67 per cent are men. Locally and globally, women remain a minority in law firm partnerships, on judicial benches and in senior in-house roles.

None of this is new. In an article published in 1876, American attorney Edith Prouty observed that “law is necessarily the most conservative of the professions and it is not strange that people are slow in accepting such an innovation as the woman lawyer”.

Nonetheless, Prouty had “faith in the future of the woman lawyer”. In the subsequent century and a half, pioneering Australian lawyers have sought to make the profession a more equal place. But change has not come fast enough.

Shining a spotlight on pay

Australia’s nationwide gender pay gap, as calculated by the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA), is 13.4 per cent. That means women’s average full-time earnings across all sectors are about $250 less per week than men. In law, the data is even worse, with a full-time gender pay gap of 23.8 per cent (although WGEA’s statistics do not cover all legal practices and largely reflect the gender imbalance at senior leadership level, rather than indicating widespread like-for-like pay discrimination).

A number of studies found pay secrecy exacerbates the gender pay gap, by amplifying discrimination and unconscious bias. Many employment contracts in Australia contain clauses forbidding the employee from discussing details of their pay with colleagues. Even at workplaces without such explicit confidentiality obligations, openly discussing salaries is still considered taboo. This opacity favours men, who – research has found – are more likely to proactively seek pay rises.

Kate* was a lawyer at a community legal centre, where secrecy shrouded remuneration discussions.

“Talking about pay was just not the done thing,” she tells LSJ. But on two separate occasions, Kate became aware she was being paid less than male colleagues doing comparable work.

“One day a colleague complained to me about being underpaid, and disclosed their salary,” she says.

“It turned out he was on $15,000 more than me.”

The gender pay gap caused discontent and ultimately contributed to Kate’s decision to leave the organisation.

“I was shocked and deeply disappointed by what I saw as clear gender discrimination,” she says.

Michelle Brown is a Professor of Human Resource Management at the University of Melbourne who has studied pay secrecy.

“When organisations have pay secrecy clauses, it has a detrimental impact on the gender pay gap,” she says.

Brown points to an American study that compared gender pay outcomes in states which prohibited pay secrecy against those that did not.

“They found that women were paid more where pay secrecy was banned. They have an impact – when you have information about other people’s pay, you are in a better position to negotiate.”

Increasingly, countries around the world are banning pay secrecy.

“Whenever they do so, we see the gender pay gap decrease – it doesn’t disappear, but it goes down,” says Brown.

While law firms may worry about impact of pay transparency on the bottom-line, Brown says it actually makes commercial sense.

“There is a persuasive body of research that links productivity improvement and lower turnover in organisations with pay transparency,” she says. This is particularly the case in workplaces with bonus schemes linked to performance, like many law firms.

“Organisations are hindering their own pay-for-performance schemes by having pay secrecy,” Brown adds.

“Those systems can’t be fully effective when there is secrecy, because you don’t know that someone else is getting better pay for better performance.”

Brown believes organisations can find a middle ground. “The public debate is often portrayed as either/or – transparency or secrecy,” she says.

“But there is useful territory in between that can satisfy the interests of employees and employers. For example, some organisations have pay bands which are transparent about the range but there might be confidentiality around where someone fits in that range.”

Targets v quotas

In the academic and public debate on improving gender equality, few topics are as divisive as quotas. Dozens of research papers argue for quotas in corporate contexts, and many advance arguments against. Proponents say they work, whereas aspirational targets have failed. Critics say they undermine merit and impact perceptions of women hired via quota systems.

While these counterarguments are not unpersuasive, there is growing recognition that structural change via quotas is needed to achieve gender equality.

“Despite three decades of women graduating law in equal and now greater numbers than men, this has not translated into a greater percentage of women at the top of the profession,” says Leah Marrone, president of Australian Women Lawyers. “It is clear that equity is not inevitable.”

Because of the barriers posed by both conscious and unconscious bias, Marrone says personal and organisational action is insufficient.

“Structural changes, such as affirmative action quotas, are needed to create change in the short term, with reporting on those measures a vital part of the mix,” she says. “Quotas are a key tool in promoting diversity and creating meaningful change.”

While more and more law firms are publicly committing to bold targets – last year Clifford Chance announced its intent to achieve 40 per cent female partners globally by 2030, in addition to LGBTQI+ and minority ethnicity targets – profession-wide quotas would require legislative action.

Quotas are not unheard of in the Australian legal profession. In 2015, the Law Society of South Australia changed its rules to require an even number of male and female metropolitan members on its council and at least three female members on its eight-person executive. The Law Society president at the time, Rocky Perrotta, feels vindicated by the decision, which faced some opposition.

“Gender equality, or at least something resembling it, should have been achieved years ago,” he says. “We were well overdue. There was no time to waste. The Society, the peak representative body of the profession, did not look by its constitution to be proportionally representative. It was essential for the Society to become properly representative as quickly as possible.”

Perrotta believes the rule changes have had the desired effect.

“In the first 139 years of the Society, we had three women presidents,” Perrotta continues. “In the past three years, we have had two women presidents (including the current president). The next woman president will be in 2023 – making it as many in five years as there had been in 139 years.”

While he acknowledges quotas may not always be appropriate in a workplace context and are perhaps better suited to representative bodies and appointed or elected positions, he is quick to dispel some of the wider criticisms.

“Targets are a cop-out [and] merit, in this context, has long been exposed as a myth” he says.

“Women should not have to wait any longer to be treated fairly and equally. Decisive action must be taken that will achieve gender equity, and as soon as possible.”