We live in an increasingly data hungry age. From 5G networks to cloud computing and now, the rise of generative AI. While we imagine invisible signals bouncing across the globe to make this connectivity possible, there’s a much more physical side to telecommunications infrastructure, that most people know little about. Undersea cables carry 95 per cent of international data traffic. New cables are being laid at a rapid rate. So how vulnerable is this critical infrastructure? And what is the legal framework protecting undersea cables servicing Australia?

In November, two undersea cables, one linking Finland and Germany, and the other connecting Lithuania and Sweden, were severed in the Baltic Sea. In a joint statement, the Foreign Ministers of Finland and Germany said the incident immediately raised suspicions of intentional damage. “Our European security is not only under threat from Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, but also from hybrid warfare by malicious actors,” they said.

The Baltic Sea is a long way from Australia, but we are not immune to geopolitical tensions and as an island continent, subsea cables play a vital role in connecting us to the rest of the world, making the everyday commerce we take for granted, possible.

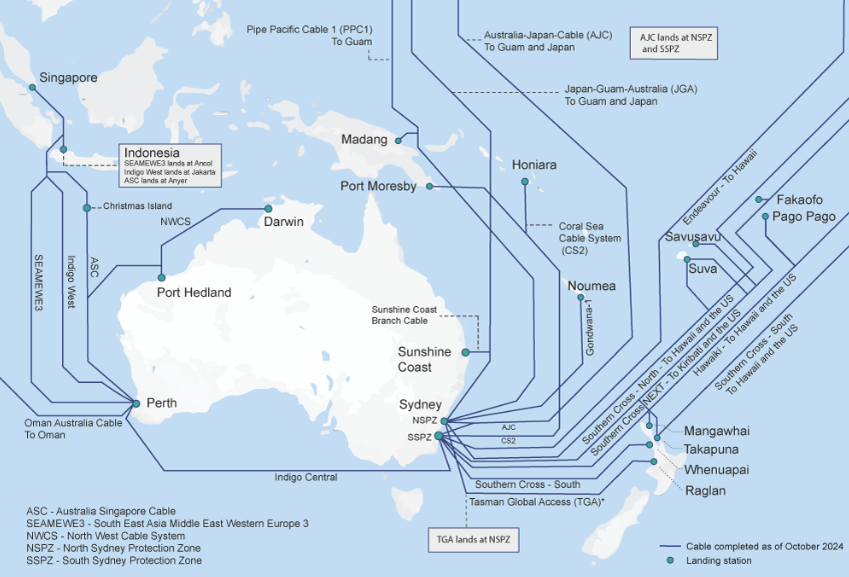

Dr Jessie Jacob is a Senior Analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. She has written extensively about undersea cables, pointing out the number of cables landing in Australia has doubled since legislation to safeguard the infrastructure was introduced in 2005.

Schedule 3A of the Telecommunications Act 1997 (Cth) introduced protection zones for cables of national significance, with criminal penalties of up to 10 years’ imprisonment for damaging a cable in one of these zones.

The Australian laws are considered gold standard and Jacob says they have served the country well. “I think that it does mean that Australia is in a better position to understand the vulnerabilities and the need to protect the cables,” she says.

Gregory Nell SC is a long-serving barrister specialising in Admiralty and Maritime Law. He agrees with the need for criminal sanctions. “That’s a good thing to have, because that focusses people’s attention on making sure that they do the right things in these protection zones,” he says.

In 2021, the Master of a container ship was charged, accused of damaging the Australia Singapore Cable, about 10 kilometres off Perth, causing $1.5 million damage. It was alleged in high winds, the ship dragged its anchor through the area, snagging the cable, which was 20 metres below the water’s surface. But in the end, the prosecution did not proceed and to date, it’s believed there have been no prosecutions under these laws.

Gold standard or not, Jacob says it can’t be a case of “set and forget”, when it comes to the legal framework. “It’s one of those things where you can’t rest on your laurels, particularly with law, you have to keep on going back and making sure it’s suitable, particularly when it comes to technology advances and changing environments too.”

Cable diplomacy

Jacob, who’s on secondment from the Australian Government, points to the recent setup of the ‘Cable Connectivity and Resilience Centre’ by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). The centre is intended to provide technical assistance and training across the Indo-Pacific region, to commission research to support governments with policy development and to share knowledge, strengthening engagement between governments and industry.

“We basically share our knowledge about resilience, help fund Pacific Island sub cables as well, so I think that demonstrates an international recognition that Australia is a bit on the front foot when it comes to cable protection.”

Further afield, there have been reports that new cables are being laid as part of a race between the United States and China for military and digital supremacy.

No new protection zones

Back in Australia, Jessie Jacob is more perplexed about why no extra protection zones haven’t been created since 2007. The current zones in Sydney and Perth, cover about two-thirds of Australia’s cable landing sites.

The Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) can declare new zones or cable owners can apply for them. Jacob says the application cost of around $160,000 is paltry compared with the repair bill for a damaged cable.

“If the cable zones work, why don’t companies then fork out the cash, which is presumably not very much for them? Because it costs quite a lot to fix a cable, why don’t they just do the zones?”

Maritime law and the economy

Gregory Nell SC says maritime law is very important to Australia’s trade and industry. “And the legal system that governs that maritime law is therefore very important as well because if those industries don’t run efficiently and if there’s no certainty as to what law is to apply, then that can be detrimental to the industry itself.”

Although it can be difficult to enforce, there are some advantages, when it comes to disputes. Nell says civil claims can be made under the Admiralty Act 1988 (Cth). “[Y]ou can arrest a ship to get security for your claim, which you can’t normally do with a normal civil claim.”

“The presence of the ship in … Australian waters is enough to give the court jurisdiction, even if the claim has nothing to do with Australia.”

Nell says the law will likely also come into play, in any offshore wind energy projects developed off the Australian coast. “They’re going to have to presumably put a zone around them so that ships can’t travel within those zones and then accidentally run into them,” he says.

So in the legal context, what happens at sea, matters a great deal to Australia.