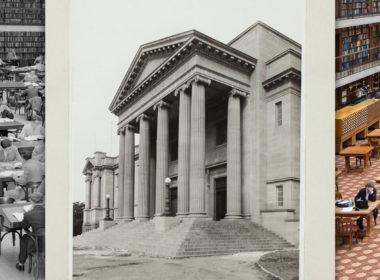

From the time it opened its doors as the first secondary school in the state’s west, the building that is now home to the Western Plains Cultural Centre has been changing the educational and cultural landscape of regional NSW. The Centre and its team have made a profound impact on the evolution of the cultural identity not just of the city, but also of the region.

PHOTOGRAPHY: STEVE COWLEY

With his hands thrust firmly into brown corduroy pockets, Kent Buchanan looks at home amid the collection of historical artefacts that sit on the same polished wooden boards he trod as a student. Both Buchanan and the building, which used to be Dubbo High School, have come a long way in the past 20 years.

The structure is now home to the Western Plains Cultural Centre (WPCC), and the born-and-raised son of Dubbo is its curator. Together they’re influential agents for change in the regional landscape.

Buchanan was once named in the top 50 most powerful people in the Australian art world, and his personal growth echoes that of the WPCC’s own evolution. The fact no one in Dubbo or the region was surprised at the nod speaks volumes about how far the community has come in terms of its own cultural development.

“When I was at high school here – in this building – Dubbo didn’t have an art gallery,” says Buchanan, now in his 50s. “Thankfully, we had a wonderful art teacher who took a group of us down to the Biennale, and that was the defining, light-bulb moment.”

As an artistic youngster, Buchanan couldn’t get out of Dubbo fast enough, impatient to leave it in his dust like many country kids living a “one horse town” reality.

“After I did my studies [in Sydney], I had no intention of ever coming back to Dubbo. I had that idea that going home was somehow a failure. How very wrong that has proved for me.”

The father of two says, had he stayed in the city, he wouldn’t have had the “incredible experience” of making such a profound impact on the evolution of Dubbo’s cultural identity.

“It’s good that I was born and raised here, and that I hated the place as a young person and kicked against it. It meant I knew what the community was like and what was holding it back in many respects,” he says.

Buchanan explains that this insight underpins his work as WPCC curator, where he has developed a unique credo: to “give people not only what they want, but also what they don’t realise they want. It’s about exposure.”

Creative transformation

It seems the humble brick edifice was always destined to blaze a trail across the lives and times of regional NSW.

Established in 1917 as the dark days of the Great War were drawing to a close, Dubbo High School was considered a significant stride forward for the state’s west. As the first secondary school in the region – few youngsters made it to “leaving certificate” – it presented an educational opportunity that undoubtedly went on to change the face of western NSW.

More than eight decades later, the then Dubbo City Council bought the site, and so began its $8.2m transformation into a gallery, museum and community creative space that would open as the WPCC in early 2007.

Since that hot February day, the centre – comprising both the historical school buildings and a state-of-the-art modern extension housing the gallery spaces and café – has been a significant focal point for the city’s journey to adulthood, helping to shake off the image of Dubbo as a cultural wasteland.

“There has been a perception that institutions in regional areas are somehow ‘lesser’. We’ve proved that wrong,” says Buchanan.

Regional areas are notoriously resistant to and sceptical about change, and there was certainly a clutch of detractors who thought the WPCC would be an elitist space. The team has worked long and hard to allay that fear.

“We’ve taken the community along with us, and it goes back to my credo of exposure,” Buchanan says. “Because of the size of the institution, we initially broke the gallery down into very distinct spaces, which meant we could put on a show people felt ‘safe’ with, and at the same time put on one that might be a bit challenging. When they came to see the ‘safe’ show, they had to go through the challenging one.” Educating people, he says, takes time.

Community belonging

Buchanan is at pains to pay tribute to the “significant role” played by local government in the development of art and culture in Australia, in regional areas in particular. “It was the vision of our local council at the time that saw the WPCC established, and they weren’t going to settle for anything mediocre. They had the vision for a really big centre. That initial decision showed great leadership,” he says, adding that this was an expression of faith that the local community was ready for the facility. “They knew the community wanted something like this, and that it would be good for the community, even those who didn’t necessarily believe in it.”

As a curator whose roots stretch deep into the western plains, Buchanan is acutely conscious that the WPCC belongs to the community, and quotes the gallery’s inaugural director, who always said it should be the “loungeroom of the city”.

“I would go further and say that, in this crazy world we live in, galleries and museums are even more important because there’s no real agenda that’s being forced on you.

“You can consume if you want, but you don’t have to look if you don’t choose so. No-one’s trying to sell you anything. I think that’s rare.”

Challenging perceptions

What’s also rare is the capacity of a facility such as the WPCC to lead a community to water and get it to drink. Even those who claim not to “get” the art are in fact allowing it to do its job. The act of prompting discussion, which many of the shows held at the WPCC over the years have done, means the art is doing what it always intended: prompting a reaction.

“There’s nothing better than two people who have opposite reactions having that conversation,” says Buchanan. “Because we influence each other. The WPCC has definitely helped educate people to ask those questions and led the community to ask the questions collectively. Art is such a powerful medium for relaying a message, but it’s non-threatening. You can look at it or not. Your choice.”

The WPCC has hosted some quite controversial shows over the years, and in this regard it breaks another mould. The facility has been a leader not just for the community of Dubbo and the district, but also in encouraging other regional communities to push the artistic and cultural boundaries.

This centre has paved the way for other centres. Yet 15 years ago the idea that Dubbo could be a beacon of creative and artistic exploration would have been quietly considered absurd. Now, though, Buchanan says the WPCC is not only respected, but also highly sought after as an exhibition space. “When I first started, there was a bit of the whole ‘why would we come to Dubbo?’ thing. Again, that’s a perception until it’s challenged. But now, big institutions I’ve built relationships with send staff out here to check us out, and they go, ‘Oh my God, this place is amazing!’”

That city folk don’t find tumbleweeds blowing across the front door of the gallery has changed the perception.

“Exactly,” says Buchanan with a smile. “I would say that for every ten shows, I probably seek one or two – the rest approach us. They’re seeking us out, not the other way around.”

It’s through those relationships that the team has been able to secure some impressive runs on the board, including one from the National Gallery, which is sending the next National Indigenous Art Triennial, titled Ceremony. “We’ve shown the last three in the series, and essentially we’ve become the only NSW venue for that exhibition,” says the proud curator. “That’s an incredible honour, which has come about through the National Gallery’s staff visiting here, and also because of our own visitation numbers – we’ve proved we can get the audiences.”

Accessing culture

As the WPCC’s cultural development coordinator, Jessica Moore is well placed to define the word “culture”. But she says it’s a tricky ask. “There’s no single definition,” she adds, but ventures, “it’s the things we do to bring us joy, to make us feel content and connected and human. For ease of funding and production, we (the WPCC) generally say culture is things that are creative, historical, things that we use to give our world meaning.

“With the term having been hijacked by so many different sectors, there’s sometimes a notion that ‘culture’ means something rarefied. There’s still this idea that culture is something you buy a ticket to. That it’s contained within the four walls of a gallery or a theatre or a museum, and you sit while culture happens in front of you. But it’s more embedded into our daily lives than we expect. So we’re really keen to ensure that the stuff we support and the culture we promote is not only within our walls, but also lived every day – it’s out in the community, it’s things you do daily. It’s a subtle thing.”

Allowing people to access culture in any way they choose is an ever-moving feast, says Moore. “It doesn’t allow you to rest on your laurels. It would be tempting, as a council, to say: ‘We’ve got a theatre. We’ve got the cultural centre. Job done’. But I’m excited about the way this council has moved to create this cultural development team: this acknowledges it’s not just about one institution. So we’re always trying something new.”

She says the public responds well to the WPCC’s active efforts to bring culture to places in which community members are comfortable. “They don’t have to just come to big edifices.”

Having been aboard since the Centre’s inception, Moore has witnessed first-hand the evolution of the WPCC and the symbiotic growth of both the centre and the community.

“There has certainly been a shift in the way people interact with it,” she says. “When it was first established, we’d have openings and people would come along and get dressed up and have their glass of wine. And while that’s lovely, we now see families coming along in board shorts on a summer’s day – I far prefer that. It’s the kind of experience we see more of now. It’s an acknowledgement that culture is an everyday thing. Now they see it as functional, like going to the markets or shopping. And the more we highlight its functionality, the more people will engage and participate, and the more it will become normalised.”

Leading the way

One of the WPCC’S goals is to ensure the experience one has in Dubbo is no different to the experience of culture available in the city. With the inclusion in Dubbo’s existing cultural mix of the Dubbo Regional Theatre and Convention Centre, and the planned development of extensive new cultural precincts for the city, Moore says the diversity of offerings is “cutting edge” and that Dubbo is “leading”.

For Moore, the city doesn’t diminish itself with a belief that its residents and visitors expect a different quality or diversity in cultural offerings than they would have elsewhere. “They really don’t. The moment people come to Dubbo, the moment they walk into this space, their expectations are completely broken down. When they see these facilities, they realise Dubbo has no expectations of itself, so neither should they.”

It’s a leadership role the WPCC and its team, along with the overarching body of Dubbo Regional Council, takes very seriously. But Moore says it must never take the form of paternalism.

“It can’t be playing a role where we say, ‘this is culture, and you can take it or leave it.’ We always want to be responsive to the community’s discussions about culture. We want to be a place where their voice is heard and shared, rather than telling them what to think.”

UPCOMING EXHIBITIONS

Because it serves such a demographically varied and culturally diverse cohort of visitors and supporters, the Western Plains Cultural Centre always has an eclectic and cutting-edge line-up of exhibitions, designed to entertain, enthral and educate.

Here’s some of what’s on offer for the remainder of 2022 and into 2023:

• Decolonise: DandalooSu

On exhibit 10 December 2022–26 February 2023

DandalooSu is Wellington-based Wiradjuri woman Sue Lousick, whose art practice involves the time-honoured Indigenous tradition of weaving from native grasses and materials. Her exhibition explores the importance and value of native flora and fauna in the agricultural and fashion industries, drawing on cultural practices using native fibre crafts. “My hope for Decolonise is that it starts people thinking about sustainable environmental management. I want to show that the native landscape is beautiful. Looking after the flora and fauna is important and I want people to look at it and see it as beautiful and something that belongs in everyday fashion.” Dandaloosu adds, “I hope the beauty and authenticity of the product helps encourage people to look to their own landscape without importing materials.”

Read our exclusive artist interview with Sue Lousick here.

• After the News: A History of The Reels

On exhibit until July 2023

It was the year 1976 – only ten years after Dubbo officially became a city. This city had one radio station and two television channels, but it gave birth to a band that would come to reshape the nation’s musical landscape into the coming decade – and beyond. The music of The Reels “defied categorisation”, but the band won the hearts and minds of audiences around Australia. This exhibition, After the News, charts the history of The Reels, from the humble beginnings of the “endlessly innovative and idiosyncratic” band in Dubbo through to its unique place in Australian rock music history.

After the News is curated by the WPCC’s Kent Buchanan, who, fittingly, grew up in Dubbo during the band’s heyday.

• Survey into The Cretaceous: Andrew Sullivan

On exhibit until February 2023

“Human courage and endurance have conquered – the explorer must change his methods.” Roy Chapman Andrews.

This unique exhibition takes a journey into the painter’s imagination, where he sees himself as “being an assigned artist with a team of palaeontologists, scientists and geographers on a survey expedition into the late Cretaceous period”. Accordingly, his brief is to record the fauna and express the experience through an artist’s eye. The result represents “a broad cross-section of species … some now extinct, some still extant today”. Presented as “the product of the journey” rather than an exploration in reality, the accompanying explanation of Survey into The Cretaceous says: “As with each individual’s human journey, it is a journey of struggle, learning, growth and ultimately evolution and, perhaps, transcendence”.