Today’s young people are more progressive than any generation before them. And voting trends are showing that they will remain progressive even as they age.

Winston Churchill supposedly observed: “If a man is not a socialist by the time he is 20, he has no heart. If he is not a conservative by the time he is 40, he has no brain.”

Like many expressions attributed to Churchill, there is no evidence to suggest he ever said these words. But the aphorism has stuck. In political speak, it has come to be known as the “life cycle effect” — the generally accepted principle that voters move further to the right as they age, from progressive to centrist to conservative.

Until fairly recently, the life cycle effect has benefited right wing parties. When a voter reaches the third stage of their life cycle, sometime in their 50s or 60s, and begins to tilt conservative, they still have many decades of votes to be cast, given increasing longevity. The period in which they vote in this way will be much longer than their time as a progressive. Often it will also be longer than their time as a centrist. This means that on average, one can expect a plurality of the voting population to preference conservative parties in every election.

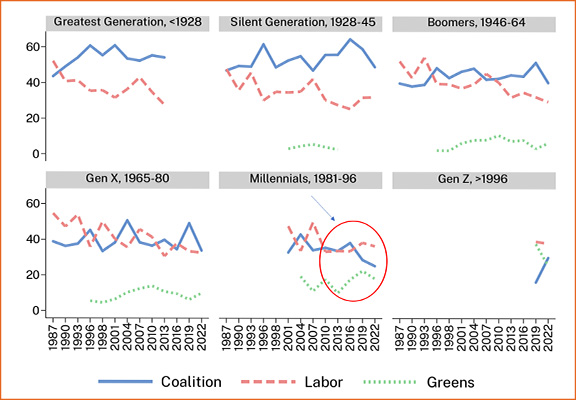

Data from the Australian Election Study (AES) shows that members of each of the Greatest Generation (born between 1900 and 1926), the Silent Generation (born 1927 to 1945), Baby Boomers (1946-1964) and Gen X (1965-1980) commenced their voting lives with progressive spirit, choosing Labor ahead of the Coalition. But as they grew older, with assets to maintain and families to look after, they typically grew more conservative.

The “life cycle effect” is the generally accepted principle that voters move further to the right as they age, from progressive to centrist to conservative.

In recent elections, and indeed for the past several decades, the majority of the voting population was made up of Generation X and older. If we accept the truth of the life cycle effect, this gave conservative parties an enormous built-in advantage. Why bother themselves with issues they deemed “woke”, like diversity and social justice, when only a minority of voters would care? Conservatives could even treat issues like climate change, rental crises and the cost of living — which young people found significantly more troubling than older voters — as secondary concerns that wouldn’t swing elections.

Of course, any political scientist will be quick to stress the limitations of the life cycle effect. For two primary reasons, Gough Whitlam, Bob Hawke and Paul Keating were each able to earn a sufficient vote share from the older populations to overcome the Coalition’s built-in advantage.

First, as the authors of the 2022 AES study note, the life cycle effect is “at best [a] mild driver of political preference”, with “election or leader-specific ‘period’ effects” often decisive. The state of the economy, the leaders’ approval ratings, and the incumbent’s performance are often far more determinative than the voter’s age.

And, secondly, it is clear that other demographics have in the past also been far more determinative than age. Take class, for example. While the Coalition has often been perceived as the party of the wealthy, the Labor Party’s very name reflects its genesis as the party of the working class, not progressive in today’s sense of the word, but representing those who fought for workers’ rights, who stood on the picket line against their deep-pocketed employers.

And yet, as the AES observes, “(t)raditional class-based voting patterns have eroded, and parties can no longer rely on their traditional base for support.” Labor’s advantage among the working class – though still statistically significant – has declined almost fourfold in the past 35 years.

Cue the increased relevance of age-based voting patterns.

The 2019 federal election provides a useful paradigm. Bill Shorten ran on reasonably progressive policies, promising reform on health, education, climate change and the cost of living, including a landmark “Fairer Tax System for All Australians”, which would have removed many of the benefits wealthier voters receive from negative gearing, capital gains tax exemptions and family trust distributions.

After six years of Coalition rule, and three Liberal Prime Ministers, it appeared that Australians were ready for change — with Labor leading almost every poll from beginning to end. Yet, in the only poll that mattered, Scott Morrison was returned as Prime Minister.

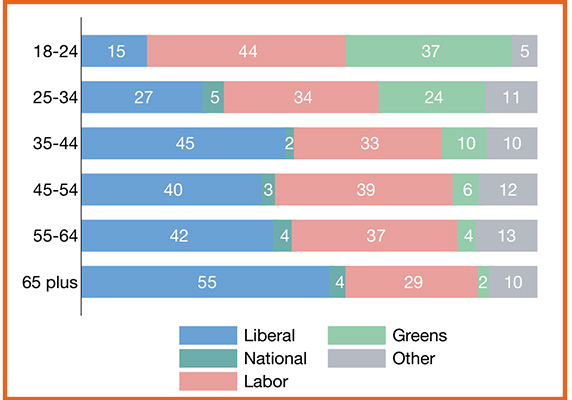

The data tell the tale. Voters selected the economy as the election’s most important issue, and those voters chose the Coalition over Labor by 3:1. Homeowners, share owners and investment property owners voted for the Coalition by big margins. Unsurprisingly, these voters all skewed older. As we can see from the graph below, all but the two youngest generations favoured the Coalition.

Despite seemingly widespread support for progressive reform, the Coalition’s older base stuck with it. The sheer size of the base — which conservatives often call the “silent majority” — overpowered the vocal, progressive minority.

But, merely four years later, that base has shrunk. It is no longer a majority.

Our most recent federal election has been revelatory.

According to ANU Political Science Professor Ian McAllister, the co-author of the 2022 AES study, Anthony Albanese’s landslide victory can be substantially attributed to two phenomena:

- First, younger generations are much further to the left than any previous generation at the same age.

- And secondly, the same younger generations are not becoming more conservative as they age.

As we have observed, at the start of each generation’s life cycle, voters were more progressive than conservative. But not all generations began as equally progressive.

For members of the two oldest generations, most of whom have now died, the margin by which voters chose Labor over the Coalition was somewhere between 1 and 10 per cent. That margin has grown in each successive generation. Strikingly, for our newest cohort of voters, the eligible members of Generation Z (born 1997-2012) voted Greens + Labor over the Coalition by more than 60 per cent.

Sixty per cent is larger than any margin by which any generation of voters has ever voted for the Coalition over the Labor Party. As University of Sydney Political Science Professor Simon Jackman – another co-author of the 2022 study – writes, “no other generation records such lopsided preferences at similarly early stages of the life [cycle].” It follows that even if the life cycle effect stays true — even if today’s younger generations grow more conservative as they age — it’s highly unlikely they would end up as conservative as older generations are today.

So what’s changed?

Perhaps most importantly, Millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) and younger voters have fewer assets at this stage of their life than senior generations. Fewer assets mean less incentive to maintain those assets — less inclination to vote for policies favourable to homeowners and shareholders and property investors.

Says McAllister: “Assets are much more important in shaping how people vote than occupational class … (I)t really doesn’t matter if you’re a tradie or a professor. What matters is the assets you own”.

According to a recent survey conducted by Resolve Strategic for The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald, 72 per cent of respondents between the ages of 18 and 34 believe they will never be able to buy a house. These voters have shifted their focus to issues that will affect them: notably, climate change; job insecurity; integrity in government; and gender and diversity issues. These are all issues on which voters favour Labor (or the Greens) ahead of the Coalition. As many of today’s young people get older and remain devoid of substantial assets, these concerns are likely to remain key motivators.

Also relevant is the fact that, as Mike Secombe writes in the Saturday Paper, today’s young people represent “the most savvy, switched-on voter cohort … in our history.” Though it may not appear that way when trying to discuss politics with an apathetic friend who doesn’t read the news, today’s young people — with unfiltered access to information online — are less likely to vote as their parents vote, and more likely to make independent decisions, than any generation before them.

Also notable, as the Centre for American Progress wrote in 2020, is that “younger generations are on a different trajectory than older generations when it comes to some of those conservatizing life events.” People are buying homes later, getting married later, and raising children later – if those milestones are occurring at all. “The conservatising effect of aging in some earlier generations may be muted.”

And finally, consider the demographic make-up of millennials and Generation Z voters, who are more educated, more secular, more diverse — racially, ethnically and in sexual orientation — and more likely to live in the city than those who came before them. The emerging picture of today’s Australian looks very different from the average Coalition voter. The life cycle effect long accepted as gospel may not apply to a secular, multi-racial, multi-ethnic generation.

Sure enough, the Coalition vote share fell in 19 of the past 20 federal, state and territory elections.

Fewer assets mean less incentive to maintain those assets — less inclination to vote for policies favourable to homeowners and shareholders and property investors.

In a speech to the Young Liberal National Convention, Shadow Attorney General Julian Leeser urged Young Liberals to broaden the party’s appeal, to find “better ways of communicating our ideas and values to young Australians.”

The party’s own review into its election performance noted a “failure to engage with ethnically diverse communities … and a general cluelessness about contemporary society.”

Over in America, Republicans are similarly concerned.

In the 2018 midterm elections, with older cohorts more divided, the Democrats’ dominance among millennials led them to a landslide victory. And by comparing the 2018 results to previous elections, we can observe that millennials became even more progressive as they aged.

Late last year, the director of polling at the Harvard Kennedy School Institute of Politics wrote an op-ed for The New York Times.

The title? “Republicans, Fear the Young”.

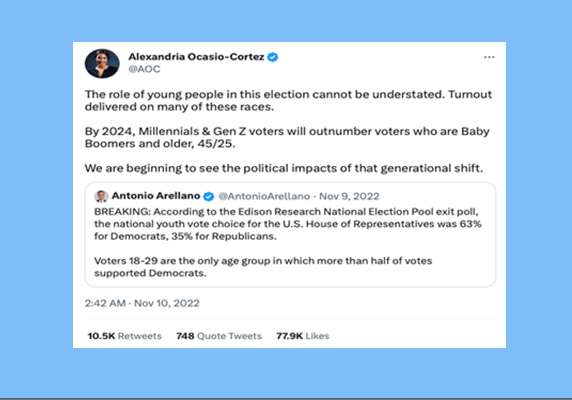

According to the Centre for American Progress, the union of Gen Z and millennial voters will account for nearly 40 per cent of voters in the next presidential election. This deeply progressive cohort may come to dominate the next generation of elections. Progressive icon and New York Congresswoman Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez is bullish, as her messaging shows.

Despite the enthusiasm among progressive activists, there are some caveats to consider. As observed above, election-specific effects are highly determinative, and in last year’s Australian federal election these effects were profound. Scott Morrison was the least popular Prime Minister to contest an Australian election since the AES began measuring leader popularity. His party faced something of a schism between the more centrist and ultra-conservative factions and ran a campaign devoid of policies. And Australians don’t often return the incumbent for a third term.

Since their defeat, the Liberals have chosen a new party leader; committed to greater emphasis on issues that affect young people; and now have an incumbent to rally against. It is possible that some millennial and Gen Z voters will be assuaged.

But, caveat aside, conservatives are right to be worried. Many of the parties’ moderate leaders are gone – replaced by Teal independents – which has resulted in a party room that looks far more conservative than the average Australian. Beyond the party room, the party’s membership remains overwhelmingly white, male and middle-aged. And the Liberals are still reluctant to embrace popular reforms, like introducing gender quotas (which Labor did more than 30 years ago) or committing to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by meaningful levels.

As Secombe writes, “the thing that kept the conservative parties competitive … was the life-cycle effect on older cohorts – the sheer number of baby boomers and the increased longevity of the silent generation that preceded them gave them great political clout.”

These voters are moving out, and millennials and Generation Z will soon outnumber them. Given that these younger voters commenced their voting life more progressive than any generation before them, and don’t seem to be changing very much, the Coalition’s very existence is threatened.

“How the Coalition addresses this overwhelming deficit of support among younger generations is perhaps the single biggest question confronting Australian politics”, the AES writes.

The policy direction of the nation is changing. Unless the conservatives change with it, their future looks bleak.