It was 25 years ago that six keen Indigenous lawyers in their nascent careers posed for a photograph that captured them striding down busy York Street in Sydney’s CBD. The snapshot by photographer Jamie James was the key image on a brochure promoting Ngalaya Indigenous Corporation, founded in 1997 by Indigenous lawyer Cal Martin together with 25 Indigenous lawyers and law students in NSW. Ngayala, from the Dharug and Eora languages, means ‘allies in arms/battle’, the name chosen by Martin to represent how Indigenous lawyers are brothers and sisters in the fight for justice. We catch up with these deadly lawyers to see the pathways their careers have taken them.

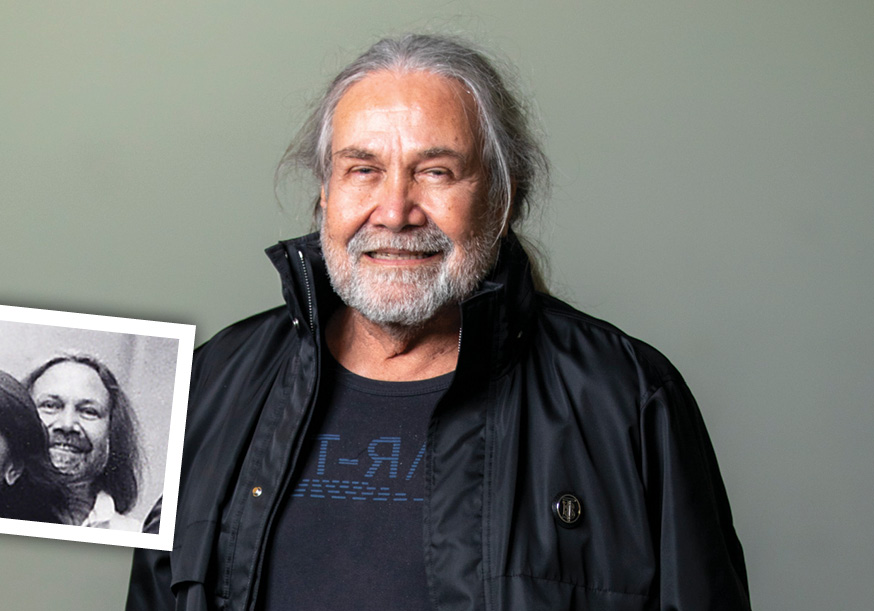

Kevin Williams

“I’m a Wakka Wakka/Gunggari man. I was born in Longreach, central western Queensland, and grew up in the bush, living in a tent for my first five years. Dad was a stockman, Mum a domestic servant. My parents thought it was fabulous that I got a high school education and finished grade 12. My father said, ‘you’ll get an education so you’re not a slave like me’. My mother said, ‘you’ll do it to help our people’.

When I was in law school many of the other students’ mums and dads were doctors, barristers, lawyers, judges, academics, teachers, and accountants. Everyone else in my grad law class had parents who were professional people and there I was, a little Blackfella. When I did law, I was lucky I had Bob Bellear by my side – a public defender barrister who became the first Blackfella judge. The legendary activist Chicka Dixon was also a mentor of mine. Good fellas.

I didn’t want to do my Master’s degree, but I did it anyway, because I think it’s important that whitefellas have someone like me, a Blackfella, teaching them black letter law. I never wanted to work as a lawyer. I only wanted to teach law.

Anne Martin and I had this idea of setting up a pre-law program at UNSW. Because Blackfellas were being let into UNSW on special admission, but that’s difficult, when you get someone who’s had, say, a grade 10 education. After some refining, we arranged it so young kids who were not academically ready for law were recommended to do a bridging program or an arts degree and gradually move into law. That seemed to work.

Now I sit on the University of Queensland’s School of Anatomy Research Ethics Committee. I’ve just stepped down as Chair of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Human Research Ethics Committee. I do sessional teaching at USC’s School of Law and Society and am the resident elder/mentor at the Buranga Centre USC. Living on the Sunshine Coast (Gubbi Gubbi country) allows me to do things for my people up here in Queensland.

To you mob studying: believe in yourself. If you’re floundering, ask for help. Ask other Blackfellas. There’s a lot more around now who have law degrees.

Professor Robynne Quiggin

“I am a proud Wiradjuri woman. I am in the legal profession, and in my current position as a professor in the law faculty at UTS, because I’ve wanted to do something to progress human rights, including consumer rights. My work has always been about finding ways to implement rights for First Nations people. So that has been the driver for me. I didn’t particularly want to be a lawyer when I was very young. If I wanted to be anything then, it was probably an artist.

On reflection, my degree and career have taught me discipline, and that’s been really useful because at times I might come up with an idea, and my career would cause me to interrogate that idea and refine it. I’d ask, does it need tweaking? Can I add something new?

I discovered that I wanted to explore and share why people are poor, and why we don’t tell the story of how poverty and lack of accumulation of money have occurred. It’s about how we’re not telling the true story of our economic position because we don’t tell the story of colonisation and the impacts on people’s lives, on their well-being. On not being able to pay their rent or necessary expenses, or being frightened that the debt collectors are coming.

As a result, when I’m lecturing and working at UTS I can, and will, always bring my whole self to the work, and show my truth. I bring who I am as a First Nations person and as a woman. I’ve never really known how to do anything different. I think being like that has given me a particular teaching style. I think we Aboriginal people are good storytellers. We engage people, we try to reach out to people, and that is our communication style.

I think we should follow whatever kind of opportunities come up and pursue what we get drawn to. And we can always make some positive change with a law degree. It’s a really good degree to have for us mob.

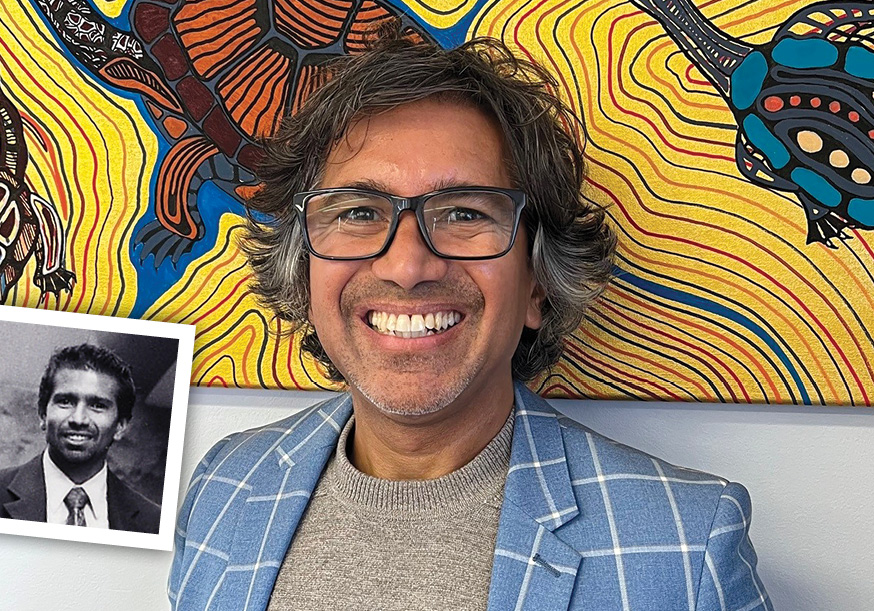

Tony McAvoy SC

“I’m a Wirdi man from the central Queensland area around Clermont. I could not have imagined, when I started my law degree, that I would be doing anywhere near the sort of work I’m doing now. I lacked self-confidence because there was a very low expectation around Aboriginal people when I was growing up; we weren’t expected to do much, or to be good at anything.

And the circumstances at home were not very good for studying: we had six people in the family, and a small house.

As a barrister working from Frederick Jordan Chambers, I enjoy taking First Nations witnesses, especially elders. I feel especially privileged to do so. There is a very distinct skill, a listening skill, that’s required if you’re representing Aboriginal people, and that is not necessarily acquired elsewhere. One of the things that I believe professionals are going to have to come to terms with is a requirement for accreditation of lawyers who have the skill to represent Aboriginal people and communities.

When working in the chambers with documents, I can really apply stories, intellect and life experiences to the problem at hand. I’m being paid to think about really complex situations and detailed facts, and sometimes I have to shake myself to remind myself of how privileged I am to be in such a position. Being able to provide that sort of service to clients and community and be paid for it is an incredible privilege.

To become a judge in Australia is a very long-term path which is hard to imagine for our people, because many of us are the first in our family to go to university or study law. But I think we will see large numbers of Aboriginal people on the various benches in Australia, and then we will be able to drive change in the legal profession.

Keeping your goals front of mind; maintaining the desire to practise and to become better is a difficult thing, unless you’re really, really enjoying what you’re doing. That is the law for me.

Shaz Rind

“I’m of Yamatji and Baluchi (‘Afghan’ camel drivers) descent.

I have an LLB and am currently pursuing my second MBA. Yet going to university was never in my wildest dreams – until a family member made me realise that education is the only reasonable way for Aboriginal people to get anywhere. So I started the Aboriginal Orientation Course at the University of WA’s Centre for Aboriginal Programmes.

Having other brothers and sisters to study with, argue with and learn from gave me an insight into Indigenous affairs I had never had before. The grassroots struggle was being translated into Aboriginal people realising the fundamental importance of learning about themselves and the western system.

The experience of university changed my life. I now have great respect for my Indigenous and non-Indigenous lecturers and mentors. We can learn and understand a great deal more with a good education.

The law gave me tools, a skill set to apply beyond the profession. It’s enabled me to channel my activism and use it to argue for Indigenous rights and opportunities in business and on Country, and gain equality and accessibility in the justice system for Aboriginal people.

It’s important to see that law can give you various careers and opportunity. It allowed me to have a really good career in native title, and also equipped me to manage complex negotiations, which is now the field I’m in now. I work in negotiating mining and oil and gas rights, with some of the biggest companies in the world, whilst negotiating for protection of country and waters by the creation of National Parks owned by Tradtional Owners.

The opportunities to study law are there, provided by the universities. It’s great to be an activist but first you’ve got to commit to your studies, work hard, get your law degree, and then look at how you can engage with the wider community.

As Aboriginal people we are one of the rare groups who are doing all we can now to make sure the next generation is stronger, smarter, faster. We are all connected, we are the community. And the stronger and healthier the Aboriginal community, the stronger the overall Australian community.

Damien Bidjara-Barnes

“I’m a Bidjara man from Carnarvon Gorge and Woorabinda in Central Queensland.

I grew up mainly around Sydney, and working as an Aboriginal man in the corporate commercial space for tier one law firms and building companies since the 1990s. I have a sense of pride and strength of character, which comes from walking a challenging and less travelled path.

I first did civil engineering at Sydney Uni, and then worked as a civil engineer on construction sites. There were hardly any Blackfellas in the commercial space then. I loved how the contracts worked, so I decided to give law a go.

In those days, there weren’t too many Indigenous programs to help you get into career spaces. I’m really happy that programs are now in place to help young people come through.

We Indigenous people in the corporate space walk in two worlds. I’m a Blackfella in the commercial space, and then when I hop back into the Indigenous community, I’m bringing my corporate knowledge. When I first kicked off in that space, there was a lot of peer pressure and negativity associated with my being in the corporate sector: ‘Brother, why are you over there?’

Reflecting on my experience, it’s so important for the young people to be able to walk in both worlds seamlessly and feel like they’re not a duck out of water in either space. As an Indigenous person it’s extremely important to bring your cultural connection, your full self into your career.

You need to challenge the internal stereotypes that limit you, to self-examine, to heal yourself, and set yourself on a path to growth and self-understanding.

Dr Terri Janke

“I am a Wuthathi, Yadhaigana and Meriam woman and owner and Solicitor Director of Terri Janke and Company.

Something that I never forget is where I’ve come from, and I’m always grateful to my parents and my grandparents, who fought for our right to education. My grandparents and their parents before them lived through very tough times to get me here. When times got tough for me, I would remember their legacy, and say, ‘I need to honour their journey and make them proud.’

That would keep me focused.

When I started law, I wasn’t aware of the opportunities. As a result I dropped out for a little while, but luckily for me I found my way back after working in Indigenous arts, and wanting to specialise in copyright.

It was very difficult to find a place in the legal profession back then, and I experienced many roadblocks. But I learnt to turn negatives into positives: I chose to flick the switch and use those setbacks as fuel for my hunger to make a change for social justice. I found role models to inspire me to continue and find my own path in the law.

We still have further to go. I’m sure the experience of racism still occurs. However, if I’d had what is available to Aboriginal law students now, maybe I would not have dropped out when I did. It is different, with so much more support. The good thing is that there’s much more awareness and cultural competency, with law firms getting involved in Reconciliation Action Plans and working together to make internships happen, as well as graduate programs for Indigenous people.

Ngalaya is the spirit, the connection and the family to get us through the hard times in the profession, and celebrate the good times. We advocate for each other and are a real support network. These Indigenous lawyers I have known for many years are doing amazing things.