Leanne Ho's early career was marked by uncertainty, but she now feels her work and values are fully aligned.

Leanne Ho has always been dedicated to social justice. “As far back as I can remember, I’ve had this strong sense of the unfairness of injustice and the need to do something about it,” Ho says. She tells the story of how, at age 12, she organised with 20 school friends to each contribute $1 per month so that they could together sponsor a child.

Now she is the Pro Bono partner at Wotton + Kearney, with a wealth of professional experience in social justice and human rights. But the path to pro bono work as a career was not always clear.

An uncertain start

If her original study plan had played out, Ho would have been a music teacher. However, her high school boyfriend had enrolled in law at the University of Sydney. And so Ho followed him there, in her own words, “without any clue about what law would really be like”.

It took a while for the law to click for Ho: “I felt really out of place at law school; unlike a lot of other people at Sydney Uni Law School at that time, I hadn’t come from a dynasty of lawyers”.

During her degree studies, she completed coursework as required, but struggled to feel a meaningful connection between her law studies and her values. In fact, in her third year she was ready to quit. Instead, she decided to do “something real” – “to see what it was all about and to feel a sense of purpose”. It was at this point Ho found a volunteer role that helped everything fall into place.

“It wasn’t until volunteering at a community legal centre that I really learned how knowledge of the legal system was powerful and that it was useful for helping people,” she says.

“I learned about the issues that people faced when they were financially disadvantaged, and all the intersections with the other issues they were facing in their lives. And for the first time, I really felt like I could help people. It’s as simple as that.”

‘Volunteering at a community legal centre … I really learned how knowledge of the legal system was powerful and that it was useful for helping people.’

Ho says, “I learned about the issues that people faced when they were financially disadvantaged, and all the intersections with the other issues they were facing in their lives. And for the first time, I really felt like I could help people. It’s as simple as that.”

By the end of her degree, Ho was beginning to see the purpose for which she was looking, but still felt like an impostor. She graduated with a transcript full of both high distinctions and bare passes. That mixed transcript fed into her lack of confidence.

“I just thought that meant that I would never be able to live up to what my stereotype of a lawyer looked like at that stage. I never even applied for a clerkship because I just thought I wouldn’t get in,” she says.

So Ho’s first professional role after university was in legal publishing. Here she found satisfaction in management roles where she could provide development opportunities for her staff. Still, she wanted more.

A leap into human rights

“When looking for purpose, [I] ended up quitting that job and going back to the community legal sector,” she said.

At the Welfare Rights Centre, Ho worked as a caseworker, and authored the handbook that practitioners of social security law rely on: The Independent Social Security Law Handbook, now in its fifth edition. It was in that role that she also found herself with another opportunity to engage in values-based practice.

“I met a guy while I was working [at the Welfare Rights Centre]. And he’d successfully applied for a UN volunteer position in Kosovo,” she says.

“At that stage, I didn’t want to lose that relationship. So I rang every phone number in the UN volunteer office in Bonn in Germany until someone would give me a job, so I could go with him … I went to Kosovo, where I was the legal officer to the Human Rights Advisory Panel that was established to hear complaints of breaches of human rights by the UN Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK). And I worked in the UNMIK Department of Justice as an international legal adviser.”

After four years in Kosovo, Ho made the move to UN Mission in Liberia.

“I started out doing legal systems monitoring and reporting on how well the courts were operating post-conflict there,” she says.

“I then moved into a role where I was the legal advisor to the mission [akin to in-house legal counsel] and managing the relationship between the UN and the Liberian government as the host country.”

Returning home

After almost seven years in post-conflict environments, Ho felt the need to come home. Applying and interviewing for social justice roles from her compound in Monrovia, she found a role at the Australian Pro Bono Centre.

Moving through several law firms, she became “the casualty of a merger,” and ultimately found herself with two opportunities: as a pro bono consultant at Wotton + Kearney, and the CEO of Economic Justice Australia. She accepted both offers.

Working in two roles in parallel, Ho saw how her human rights experience could influence law reform at a high level. Through Economic Justice Australia, she had “a firm seat at the decision-making table” and would eventually represent the organisation in critical meetings and forums with government, as “part of a movement to ensure that the economic and social safety net is there when we need it.”

The necessity of this safety net has been highlighted in recent years:

“COVID taught everyone that anything can change in an instant. Any of us could need the social security system, any of us could be in a position where we need financial support,” she says.

‘COVID taught everyone that anything can change in an instant. Any of us could need the social security system.’

A foot in both worlds

After five years in both roles, she moved into her current role of Pro Bono Partner at Wotton + Kearney. For her, this is a wonderful combination of the various areas of her professional experience.

“That work I’ve done in the not-for-profit sector has informed the work that [I am doing] at Wotton + Kearney because it keeps me up to date with what the needs are in the community,” she says.

“Because I’ve had a foot in both worlds, I’ve got relationships, both in the law firm, but also in the community sector. So I’m in this position to understand what contribution pro bono law firms can make – with the skills and the expertise of the lawyers in the firm, what they can contribute – that’s going to be useful to the organisations who are representing clients at the coalface and advocating in their interests.

“I really love that I can draw on all the different experiences I’ve had, and all the networks that I have, to bring together these ideas that can help move human rights forward.”

For Ho, professional satisfaction comes from seeing real change. Nonetheless, the reality of the legal profession, she says, is that “law reform can take a really long time – you start advocating for something and it can be years, sometimes decades, before you see any kind of movement.”

Which is what makes her recent work such a key career highlight. When Ho was still with Economic Justice Australia, she and her team were behind changes to “how members of a couple are assessed in the social security system, which means that people experiencing family and domestic violence are going to have better access to financial support, [and] that they can leave.”

“So they don’t have to make that terrible choice between either staying in a violent situation, or leaving with their children and facing desperate poverty,” she says of the work, which involved meeting with MPs and government officials.

Not an easy process

The process of bringing about change was by no means easy. Through Wotton + Kearney, Ho was “able to gather a team of lawyers, who did some research on how this issue was dealt with in other countries – progressive countries, like Scandinavia, but also New Zealand and the UK.”

“That provided some confidence in the proposed changes, because the government was saying to me, ‘it makes sense, but what are the unintended consequences? How’s it going to work in practice?’” she says.

Nonetheless, there were plenty of setbacks – “but we didn’t take “no” for an answer,” Ho says.

Ultimately, the work paid off: “In May [2023], the government announced the change to the policy, and now family and domestic violence is a factor that will be considered when deciding whether someone is a member of a couple for social security purposes.”

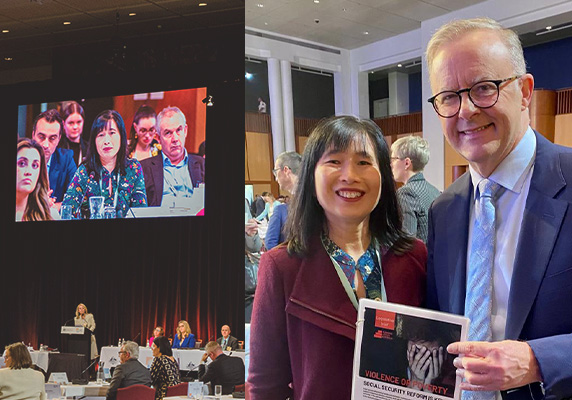

This achievement has been recognised in a wide range of places. Recalling the government’s Jobs and Skills Summit at which she was one of the community leaders invited to make a speech, Ho says: “I handed a copy of the brief to the Prime Minister, and took a selfie with him holding it.

“That had signatures of hundreds of representatives of domestic violence organisations and community organisations and business leaders and a whole broad coalition of supporters.”

Perhaps the most satisfying evidence of the change came for Ho at a recent CBA event.

“A woman came up to me and said that when she went to Centrelink they decided that she could be assessed as a single person,” she says.

“Because her husband was earning a lot of money, she would have not been entitled to any payment, but because of this policy change, she and her children have left, and she’s got back on her feet.

“That is the best possible outcome. That’s a real highlight, to have someone for whom that policy change has actually changed her life.”

Lessons learned

Throughout her varied career, and recent achievements, Ho has learned the value of rest – and she’s about to spend several months on holiday.

“[I’ve had an] extremely intense couple of years, where I’ve been on high alert all the time … I’ve recognised the impact that kind of constant stress is having on my health, and my relationships,” she says.

Other than regular rest, Ho has found that choosing the right relationships is key to managing the stress of her work.

“I invest time in the people who enrich my life,” she says. “I’ve worked with such fantastic colleagues over the years. I’ve been really fortunate to have friends that I work with, and they’re just such a lifeline in times of extreme stress. I think there’s so much pressure on us, [we’re] pulled in so many different directions. [So] I’ve really given myself permission over the latter years of my career to pick and choose who I’m going to invest time in.”

Ho reflects that her early years in law were typified by a lack of confidence, and despite her achievements this has continued to be an issue.

For her there are two key lessons. The first is the power of building relationships. Early on, perfectionism prevented her from reaching out to new contacts and potential mentors. Now Ho is keen to encourage others to be brave.

“I’ve learned that relationships are such a big part of being successful in the law, in any career,” she says.

“I wish I’d learned earlier not to be afraid to create networks and reach out to my own, whether that’s friends or lecturers or colleagues, or just people who post ideas that resonate on LinkedIn. People often just write to me on LinkedIn, and ask if they can have a coffee […] I wouldn’t never have done that in my early career. But that has led to so many really important relationships in my career.”

The second lesson is to embrace learning and change.

“I’ve learned to accept that I will always be learning,” she says.

“And it’s okay to try something and then change direction if it’s not right for you. I’ve done this many times. And I’ve landed where I am today by just having a go.”