“I have had the benefit of working with female partners who have been really successful at what they do. I always thought it was possible to become a partner.”

The 2020 National Profile of Solicitors has been published and reveals insights into the growth and demographics of solicitors across Australia.

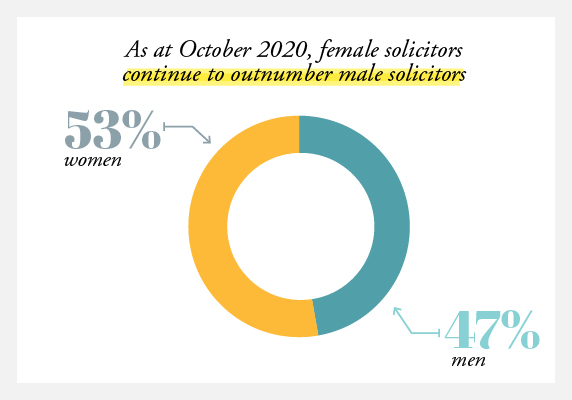

It’s official: female solicitors outnumber male solicitors in every state and territory in Australia. The 2020 National Profile of Solicitors in Australia was published in July and reveals women have been joining the profession in soaring numbers since 2011, now accounting for 53 per cent of solicitors nationally. While women solicitors surpassed men in total number across the country back in 2018, the latest data shows female solicitor numbers have also overtaken men in every jurisdiction.

“The big item in the latest report that has been of interest to people is that it is the first time women [solicitors] have outnumbered men in every state and territory in Australia,” says Sonja Stewart, CEO of the Law Society of NSW.

The National Profile of Solicitors report is undertaken by Urbis and published by the Law Society of NSW on behalf of the Conference of Law Societies (the coalition of law societies representing each state and territory) annually. It is the only study of its kind to capture a national demographic profile of practising solicitors around Australia and compares data with the Law Society of NSW’s first national profile, which was released in 2011, and provides ground-breaking analysis of the legal profession.

“We’re [NSW solicitors] a big profession, we’re an important part of the justice system – NSW accounts for 43 per cent of the legal profession nationally,” Stewart says.

“This is a project we take pride in. It’s important to help us obtain data to understand the legal profession, its growth and the types of law that people are practising in, and to understand some trends.”

One of the trends the report highlights is the huge growth in the solicitor profession overall. The number of solicitors nationally has grown 43 per cent since 2011 – surging to almost one and a half times its previous number.

However, a glaring contrast to this growth is the comparatively lagging number of Indigenous solicitors.

In 2020, just 632 solicitors across the country identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, representing 0.8 per cent of the profession. This is despite census data showing the proportion of Indigenous Australians across the population nationally is closer to 3 per cent. The report notes this is a trend that has perpetuated since 2014.

“One of the interesting things is to think about the data and what does that actually mean?” says Stewart.

“There is some further consideration we’re going to be giving to the lack of growth, the stagnation of Indigenous representation in the profession. And what can we as a law society be doing to address that?”

The rise of women solicitors

The historic new tilt to gender balance in the legal profession does not come as a complete surprise to lawyers who have been following the data in previous National Profile reports.

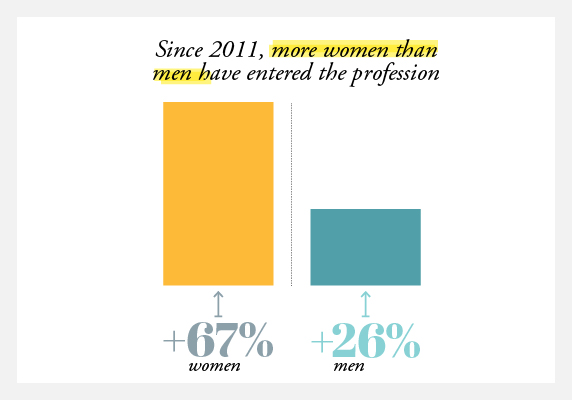

While solicitor numbers increased dramatically across both genders in the past decade (a total 45 per cent growth in the national profession since 2011), the report shows female numbers have surged to a greater extent. The number of male solicitors grew by 26 per cent over the past nine years – while the number of female solicitors skyrocketed by 67 per cent.

The report suggests there are greater numbers of women studying law at university and thus entering the profession at higher rates than men. A 2018 report by the Grattan Institute backs up this theory: it found women have made up a majority of university students in Australia since 1987, and that female law graduates have outnumbered male law graduates in Australia since 1993. In 2012, the National Attrition and Re-engagement Study (NARS) Report by the Law Council of Australia noted female solicitors comprised more than three fifths (61 per cent) of new solicitors admitted that year.

Special Counsel at Clayton Utz, Amanda Lyras, has watched this trend perpetuate throughout her career as a solicitor practising in top-tier employment law.

“It [the data] didn’t surprise me to be honest, I think we have traditionally had a large number of women represented in the junior ranks, all the way up to senior associates,” she says.

“The problem we have grappled with as a legal industry is in elevating those women to senior leadership positions.”

Lyras began her career as a graduate lawyer in 2011 at Herbert Smith Freehills, one of Australia’s “Big Six” top-tier firms, before joining Clayton Utz in 2019. She says the visibility of senior women in her practice area and the accessibility of female role models has been a major motivating factor for her.

In other words: working under senior women lawyers helped her see what she could be.

“During my summer clerkship, I was allocated to two female partners in different practice groups,” she says. “Then when I was doing my graduate rotation, in two out of the three practice groups, I was working with female partners. In terms of my career journey, I have had the benefit of working with a number of female partners who have been really successful at what they do. I always thought it was possible to become a partner.”

Amanda Lyras, Special counsel employment law, Clayton Utz

Amanda Lyras, Special counsel employment law, Clayton Utz

Lyras is a member of Clayton Utz’ in-house diversity and inclusion network, Momentum, as well as the Law Society of NSW’s Diversity and Inclusion Committee. She is part of the team overseeing the Law Society’s Charter for the Advancement of Women, which launched in 2016 to provide policy settings for legal workplaces to adopt that would encourage promotion and retention of women. This year, the Committee, including Lyras, revamped the Charter to include a section calling on firms to eliminate sexual harassment and bullying. About 300 law firms and legal workplaces have signed up since 2016.

However, Lyras’ reflection on the lack of women in senior levels of the law highlights an ongoing challenge for the profession.

While the National Profile of the Profession does not capture the level of seniority of solicitors according to gender, each year the Australian Financial Review undertakes a survey of partners in Australia’s largest mid- and top-tier law firms. This year’s 2021 Law Partnership Survey reveals only 30 per cent of partners at those firms are female. Little corresponding data exists on in-house, government or small firm sectors; although anecdotally, there may be better gender parity in senior levels of those sectors.

“In the past, becoming a partner in law or a legal organisation may not have been ideal in terms of allowing for work-life balance,” Lyras says. “The industry as a whole still needs to improve on how it works with women, identifying talent and supporting and encouraging them to have a fulfilling and successful career.”

She also notes that firms need to look beyond gender and turn their attention to promoting broader forms of diversity such as cultural, LGBTIQ and socio-economic background. If they don’t, she says, many clients will vote with their feet and look elsewhere for legal representation.

“Diversity is important not just in terms of providing opportunities for staff internally, but also for connecting with our broader client base, who themselves are diverse and are demanding greater diversity in their service providers,” she says.

A boom in numbers across the board

Continual change, adapting to new precedents and legislation, and “sheer variety” has kept a mind like Peter Rosier’s, an accredited specialist in property law, in the profession since his admission almost 50 years ago.

“It requires a brain trained by both experience and tuition to process a factual matrix and apply that to the law as it is understood. And, because the facts are often novel, and the law not necessarily certain, the task can be interesting, difficult and uncertain,” Rosier, the Principal at Rosier Partners Lawyers, tells LSJ.

“That need for a certain creativity, the fact that a lot of a lawyer’s work can require high-level thinking makes the practice of the law a generally pleasing occupation.”

The data suggest many share his view. There are now 83,643 solicitors nationally: 26,066 more than in 2011, with boosts in number both at the dawn and twilight of legal careers.

Peter Rosier, Principal, Rosier Partners Lawyers

Peter Rosier, Principal, Rosier Partners Lawyers

“That need for a certain creativity, the fact that a lot of a lawyer’s work can require high-level thinking, makes the practice of the law a generally pleasing occupation.”

More solicitors are working past the age of 65, however the mean age of lawyers [42 years] has remained relatively consistent, as the growth of those working later in life is offset by high university numbers leading to more young lawyers entering the profession.

The law’s “improving accessibility” is also driving the dreams of Kate Thomas, a recent graduate, who tells LSJ, “[growing up] I had no exposure to the legal profession, and so I wanted to study the law in order to empower myself and those around me.”

“I want to use my legal skills to tackle ongoing and emerging legal issues – such as sex discrimination and inequality, environmental management and how we can improve the law’s relationship with Indigenous Australians,” she says.

“I also want to be a role model for others in breaking down barriers.”

The proportion of male solicitors aged 65 years and over has been increasing steadily in the past decade, from 7 per cent in 2011 to 13 per cent in 2020. This is in line with the large increase since 2014 of solicitors aged 65 years and above, up by 59 per cent.

“I came to learn very quickly of the satisfaction from the sheer variety of situations to which legal knowledge could be applied,” Rosier says.

“We may now have better tools to undertake the task of understanding our clients’ needs and managing their expectations as we endeavour to convert instructions into a reality, but essentially, the process remains the same.”

Despite the uncertainty of the past 18 months, or perhaps because of it, many of the over-65s in the profession have no signs of slowing down yet.

“This continuum over my near 50 years’ of practice of the application of legal knowledge with the understanding that there may be no certain answer to interesting and always varying facts is what has kept me in practice as a property lawyer and litigator,” Rosier says.

“It is what will keep lawyers entering the profession in 2021 working in the profession for many years. It is not easy, I admit: I found the first 48 years to be the hardest even if I stopped waking up in the middle of the night worrying about some problem or other after 10 years.”

Low proportion of Indigenous lawyers is disappointing

In a year that saw the Law Society of NSW appoint its first Indigenous CEO, Yuin woman Sonja Stewart, the lack of Indigenous growth in the profession nationally has been disappointing.

The National Profile reveals just 0.8 per cent of solicitors across Australia identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. The report notes this low proportion of Indigenous solicitors has remained relatively stable since 2014 – when the first data on Indigenous cultural background began to be collected.

“It’s a very clear thing in the data, isn’t it?” Stewart says.

“There’s the increase in the profession over the nine years of 45%. There’s more women than men in every state and territory, and yet there’s a stagnation of Indigenous numbers. People in roles like mine across the country would be looking at all of those things and thinking, what does it mean, for our profession going forward?”

First Nations Advisor and Lawyer at Ashurst, Trent Wallace, a Wongaibon man who grew up in Darkinjung Country on the NSW Central Coast, celebrates the news that “the future is female” in law. However, he also wants it to be First Nations.

“The Australian legal system has all too often been wielded as an axe that falls upon First Nations peoples most harshly. And the legal profession, like others, continues to struggle to be a representative one,” he says.

“One major problem is that First Nations subjects are offered as optional electives, but too rarely as core units. This relegation of First Nations subjects is perilous, and often has a flow on effect for how law is practised in Australia, too often failing to take into account First Nations cultures.”

Wiradjuri and Ngunnawal woman Taylah Gray, who is a criminal defence lawyer at Aboriginal Legal Service NSW, agrees that the legal education system is not built for “disadvantaged people like us”.

“The lack of Indigenous lawyers in Australia is no coincidence. Historically, we have been excluded and discouraged from accessing the educational sphere for decades,” she says.

Both Wallace and Gray say having visible Indigenous role models in senior levels of the profession has been invaluable to their personal journeys in becoming lawyers. They say more should be done to promote First Nations lawyers into those positions, and that self-determination is essential when deciding the best strategies to adopt in growing the Indigenous talent pool.

“We need more First Nations Peoples in positions of clear authority and have cultural expertise recognised as the winning formula,” Wallace says.

“If you want more representation, interrogate your actions, hire First Nations expertise and embed the work in a ‘business as usual’ model of operation. The efforts must be shared among schools, universities, PLT programmes and the profession to ensure there is solidified support at all levels. A ‘want’ will only be satisfied through action.”

Stewart says she is aware of firms and employers “actively looking at ways to attract, retain and grow talent” of the Indigenous legal workforce. She also hopes last months’ NAIDOC special “Blakout” edition of LSJ – which she proudly guest edited – had an impact on aspiring lawyers across the country.

“People might say that is just a magazine, but it was distributed to every Indigenous law school student in NSW,” she says. “And I believe if you can see it, you can be it. If just 15 people read it and say, ‘Yep, this is a really diverse and worthwhile profession’, that would be a great outcome.”