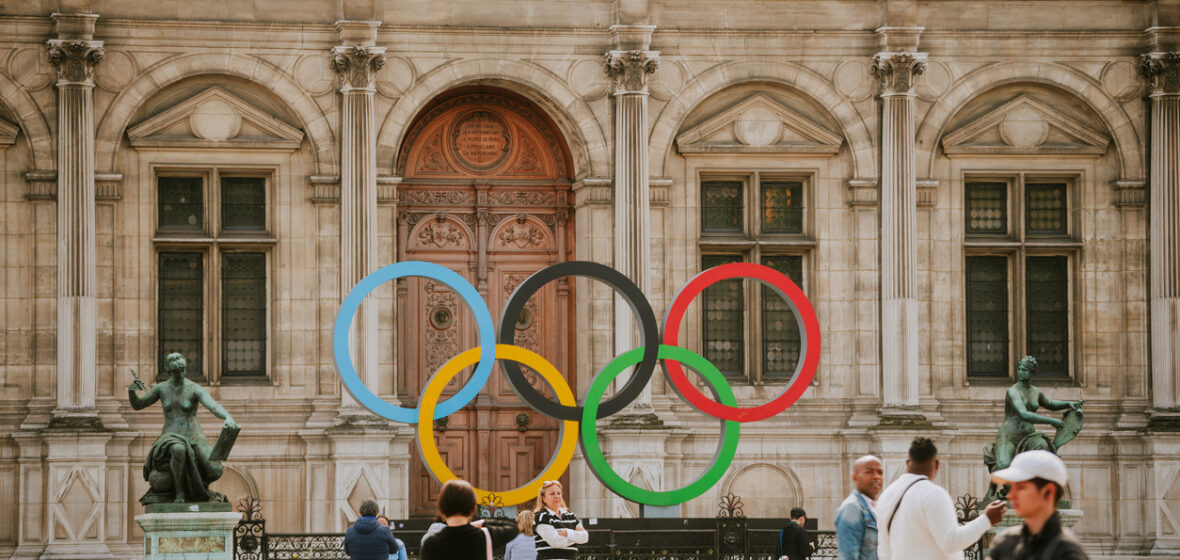

On July 26, Paris officially opens the 2024 Summer Olympics. The event is the culmination of years of work in construction, planning, infrastructure, security technology and in newly introduced legislation.

In May 2023, France introduced new legislation ostensibly to address security concerns around the Paris Olympics. The laws raised concerns amongst privacy advocates for enabling facial recognition, video surveillance augmented by AI to automatically detect security issues, use of body scanners and data retention, plus access to surveillance footage by transport agencies that previously did not have such comprehensive access.

The new laws extend well beyond the Olympics events in Paris, and may set a precedent for future Olympics and for other nations within the European Union. Australians may face a similar conundrum over the extent and intrusiveness of security measures when Brisbane hosts the Summer Olympics in 2032. While laws are somewhat easily introduced, they are much harder to wind back.

As reported by Politico in late April, France has reduced by half the number of people allowed to attend the proposed ceremony on the Seine to around 300,000, while strengthening entrance requirements in acquiescence to growing terrorism concerns.

LSJ spoke with a Polish lawyer with expertise in technology, privacy, and its intersection with human rights and security.

Karolina Iwańska is a Digital Civic Space Advisor at the European Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ECNL), responsible for ECNL’s EU advocacy, particularly on the EU AI Act. She is also involved in research and policy analysis at the intersection of security, counterterrorism, and technology. Prior to joining ECNL, Iwańska worked as a lawyer and policy analyst at the Warsaw-based digital rights organisation Panoptykon Foundation.

As she tells LSJ, “Once an ‘exceptional’ surveillance measure is allowed, it’s very easy to normalise it and make it permanent.”

She says the new laws could extend their remit well beyond the purposes originally stated.

“Once a biometric surveillance infrastructure is in place, the risk of abuse and repurposing it (so-called ‘function creep’) is very high. In addition, we see a dangerous trend of using the excuses of national security for surveilling protests or treating protesters as extremists, in which case surveillance becomes even more secretive, opaque and outside of public scrutiny,” Iwańska says.

In May 2023, France enacted a package of laws designed as a framework for the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games held in Paris and surrounding cities between July 24 and September 8 this year. In January last year, French senators approved legislation for AI-powered video surveillance. Law No. 2023-380 resulted from a series of parliamentary amendments, and includes legal provisions affecting various aspects of the Games. The most controversial aspect is the security measures that Article 7 of this Law enables.

Article 7 of Law No. 2023-380 provides authority to French law enforcement authorities to use intelligent video surveillance (facilitated by AI technology) through to March 31, 2025. The cameras, both installed and attached to drones, will monitor individual and crowd movements to identify suspicious behaviour in real time, with the ability to determine what is suspicious and what may be a cause for sending in authorities (an abandoned bag, for example). Article 10 specifically enables a provision for the use of algorithms to captured images, since the Internal Security Code (Law 251-1) already regulates the installation and use of surveillance cameras and drones in public spaces, and collection of images.

Iwańska says, “In our view, the new law contravenes the principles of necessity and proportionality, two conditions that must be fulfilled under international human rights law to introduce restrictions to rights and freedoms. Algorithmic surveillance of public spaces that France is deploying can have a chilling effect on the freedom of expression and the right to protest. It interferes with everyone’s right to privacy. It also creates the risk of discrimination if it classifies situations such as begging or stationary assemblies as ‘atypical’ or ‘risky’.”

Data collection safeguards

Amnesty International released a statement that said, “While France promotes itself as a champion of human rights globally, its decision to legalize AI-powered mass surveillance during the Olympics will lead to an all-out assault on the rights to privacy, protest, and freedom of assembly and expression.”

In March 2023, 38 civil rights organisations had opposed the introduction of the new laws through an open letter to the French National Assembly.

In part, that letter reads: “The proposal paves the way for the use of invasive algorithm-driven video surveillance under the pretext of securing big events. Under this law, France would become the first EU member state to explicitly legalise such practices. We believe that the proposed surveillance measures violate international human rights law as they contravene the principles of necessity and proportionality, and pose unacceptable risks to fundamental rights, such as the right to privacy, the freedom of assembly and association, and the right to non-discrimination.

“We call on you to consider rejecting Article 7 and to open up the issue for further discussion with national civil society. Otherwise, its adoption would establish a worrying precedent of unjustified and disproportionate surveillance in publicly accessible spaces.”

Additionally, Law No. 2023-380 broadens the interagency cooperation between the Paris Transport Authority (RATP) and National Society of the French Railways (SNCF) agents, who will be granted much greater access to video surveillance images to purportedly enable Paris police to “maintain public order in the Paris Region during the Games”.

Perhaps most concerning to advocates for privacy is the new provision for “screening” of all individuals attending major events. Athletes, sponsors and media will be subject to body scanners upon entry to stadiums and other venues with a minimum capacity of 300 people.

France adheres to the personal data protection provisions within Regulation (EU) 2016/679 and the provisions on information technology, files and freedoms within Law No. 78-17 of 1978. Article 10 prohibits the use of biometrictic identification systems or facial recognition in real time collection of images, however it is possible that police could apply facial recognition measures to the recorded images.

While the new law does not introduce the provision for facial recognition for criminal investigations, this is already allowed via the French Criminal Procedure Code (articles 230-6 and R.40-26) but the significantly expanded surveillance and number of individuals who will be caught on cameras within the Paris area exposes many more individuals to surveillance and police interest than ever before.

Iwańska tells LSJ, “I am not familiar with any existing laws in France that would allow the so-called ‘post’ biometric identification. This type of surveillance would also require compliance with the GDPR and the principles of necessity and proportionality. However, a law allowing this practice explicitly is currently being discussed in the French Assemblee Nationale and is likely to be adopted. This is precisely what ECNL and nearly 40 other CSOs warned against: once an ‘exceptional’ surveillance measure is allowed, it’s very easy to normalise it and make it permanent. This new law, focused on ‘transport security’ would make it possible to analyse CCTV from public transport to be analysed with algorithms way beyond the Olympics, until 2027.”

AI algorithms and inherent discrimination

Algorithms are trained by humans and, for the most part, evidence has indicated it is mostly white men programming AI and, even unintentionally, they are transferring their own biases to the technology.

According to Amnesty International’s “Ban The Scan” campaign, “Facial recognition technology can amplify racially discriminatory policing and threatens the right to protest. The technology is developed through scraping millions of images from social media profiles without permission.

Black and minority communities are at risk of being misidentified and falsely arrested – in some instances, facial recognition has been 95 per cent inaccurate. Even when it “works”, it can exacerbate discriminatory policing and prevent the free and safe exercise of peaceful assembly, by acting as a tool of mass surveillance.”

While Article 7 – III asserts that algorithmic video surveillance systems will not process biometric data, this claim contrasts with the practical application of the technology. Article 4(14) of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) defines biometric data as “personal data resulting from specific technical processing relating to the physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a natural person, which allow or confirm the unique identification of that natural person”. AI-augmented cameras are designed to detect predetermined suspicious activity in public spaces, requiring the real-time capture and analysis of individual people and their behaviour, including their posture, gestures, speed and style of movements, and their appearance. These all equate to “unique identification.”

The new laws seem to enable algorithms to assess body movement, gestures, behaviour and place. How does this make sense when the government claims there is no biometric data recorded, nor unique identification?

Iwanka says, “In my opinion the government’s assessment is entirely incorrect and at odds with EU data protection law. The GDPR defines biometric data as ‘personal data resulting from specific technical processing relating to the physical, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a natural person, which allow or confirm the unique identification of that natural person’. French authorities argue that they will not ‘identify’ people, meaning they will not aim to discover the person’s name, but this is not in line with the GDPR. Even the ability to isolate specific people from the background, singling them out from a crowd or their surroundings, does constitute ‘unique identification’.”

Human Rights Watch (HRW) have argued this law presents “a grave risk to fundamental human rights and existing evidence of actual inefficiency of video surveillance to prevent crime or security threats”. Their concern is that the French government “has not demonstrated how this proposal meets the principles of necessity and proportionality, nor meaningfully engaged with civil society about the measure.”

Article 7, according to HRW, “does not meet the three-part test of legality, legitimate aim, and necessity and proportionality”, conflicting with human rights obligations according to international treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights.

The implications closer to home

Ahead of the Olympic Games taking place in Brisbane in 2032, the Queensland Government is already planning infrastructure and transport projects to house the athletes and international professionals, additional hotels for attendees, while also looking ahead to how the four athlete villages will be transformed into permanent housing after the Olympics.

Whether last-minute security laws, akin to those in France, will be rushed through Parliament remains to be seen.

Iwańska’s concern for the nature of France’s new laws and their ongoing impact on civil rights serves as a public warning, however.

“The mere existence of untargeted algorithmic video surveillance in publicly accessible areas can have a chilling effect on fundamental civic freedoms, especially the right to freedom of assembly, association and expression. Biometric surveillance can reduce people’s will and ability to exercise their civic freedoms, for fear of being identified, profiled or even wrongly prosecuted. Because this measure targets everyone in the public space, it also threatens the very essence of the right to privacy and data protection,” she says.

“The law dangerously expands the reasons justifying the surveillance of public spaces. If behaviours such as begging, lingering or stationary assemblies are classified as “risky”, there is the threat of stigmatisation and discrimination of people who spend more time in public spaces, for example due to their homelessness or disability.”

“In my view, extending this ‘experiment’ beyond the Olympics is already an indication that the possibility to use these systems will be extended. In fact, our concerns that algorithmic surveillance will not be abandoned after 2025 are already unfortunately coming true with the new proposed law on allowing ‘post’ biometric surveillance until 2027, also as an ‘experiment’. This fits into the pattern observed during previous Olympic games which similarly served as a terrain for experimentation with increased state powers later repurposed for non-emergency situations.”