A recent decision to edit the works of Roald Dahl for a new generation has sparked criticism from other authors and household names. However, the practice of adapting children’s stories to new generations is perhaps more common than most realise.

A decision by Roald Dahl’s UK publisher to tweak and revise some of his works stoked the flames of censorship in the era of so-called “woke” appeasement. But are the criticisms warranted, or is there a good reason to update beloved children’s classics to remove racial stereotypes and reflect changing gender norms?

“The picture showed a nine-year-old boy who was so enormous he looked like he had been blown up with a powerful pump”. This is how Roald Dahl describes Augustus Gloop in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

Except, it isn’t. In the author’s words, and in the version you may have read before, Gloop is described as not just “enormous”, but “enormously fat”.

In early March, Roald Dahl’s publisher in the UK, Puffin books (owned by Penguin books), revealed they are republishing the author’s most famous children’s books with updated, more inclusive language. The example above is innocuous, and not many readers would have noticed had it been quietly changed without much fanfare, but other changes are more evident.

In The Witches, the revelation that witches are bald underneath their wigs is now followed by the addendum: “There are plenty of other reasons why women might wear wigs, and there is certainly nothing wrong with that”.

Two whole verses from James and the Giant Peach, “Aunt Sponge was terrifically fat / And tremendously flabby at that,” and “Aunt Spiker was thin as a wire / And dry as a bone, only drier”, were replaced by “Aunt Sponge was a nasty old brute / And deserved to be squashed by the fruit,” and “Aunt Spiker was much of the same / And deserves half of the blame”.

“Small men” becomes “small people”, and “female” is replaced with “woman”. Mrs Twit is not “ugly and beastly” anymore.

Puffin has made over 100 changes to the original texts with the help of Roald Dahl Story Company and Inclusive Minds, a group that works to add a more inclusive language to children’s books.

According to Alexandra Strick, co-founder of Inclusive Minds, the aim is to “ensure authentic representation by working closely with the book world and with those who have lived experience of any facet of diversity”.

This included removing references that correlate ugliness with being evil (Matilda’s Miss Trunchball is not “horse-faced” anymore), pejorative representations of minorities – like Charlie and Chocolate Factory’s Oompa Loompas – or just general terms that can be reappropriated or misconstrued to cause harm or offence.

Is it an overreaction? Perhaps, but for the Roald Dahl Story Company, which manages the estate of the late writer and was purchased by Netflix in 2021, an expected one.

“When publishing new print runs of books written years ago, it’s not unusual to review the language used alongside updating other details, including a book’s cover and page layout,” a company spokesperson said.

“Our guiding principle throughout has been to maintain the storylines, characters, and the irreverence and sharp-edged spirit of the original text. Any changes made have been small and carefully considered.”

James and the Free Speech

As quick as Puffin books announced the changes, reactions from social media started pouring in from other writers, politicians and other household names. The main take was that this change constituted censorship and a breach of the right to free speech.

Salman Rushdie, who knows what it means to have his voice silenced, tweeted: “Roald Dahl was no angel, but this is absurd censorship. Puffin books and the Dahl estate should be ashamed”.

Phillip Pullman, the author of His Dark Materials, suggested instead to stop printing his books. “It doesn’t do everything very much. If it does offend you, let him go out of print,” Pullman told a British radio host.

PENAmerica, a group of thousands of writers dedicated to preserving free speech in literature, expressed concern about the changes. Suzanne Nossel, their CEO, posted a thread on Twitter about the organisation’s concern about the proposed changes.

“The problem with taking license to re-edit classic works is that there is no limiting principle. You start out wanting to replace a word here and a word there and end up inserting entirely new ideas (as has been done to Dahl’s work),” she said.

Reactions were not exclusive to the literary world with British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak releasing a statement calling for a defence of the right to free speech and expression.

Charlie and the Controversy Factory

After a week-long social media storm following the announcement, Puffin Books decided to make both edited and classic versions available.

“We’ve listened to the debate over the past week which has reaffirmed the extraordinary power of Roald Dahl’s books and the very real questions around how stories from another era can be kept relevant for each new generation,” the publishing house wrote in a statement on their website.

Adapting children’s books is nothing new, and for a good reason. Sensibility changes with time, and what is deemed acceptable one day can quickly become taboo the next day. For adults, it’s easy to discern this difference, but children may struggle with understanding context.

Children do not watch Disney’s Dumbo because of the offensive racial representation. No one would miss the scene if the “controversial” crows were not in it. A child watching that scene without knowledge of its context can be more damaging to its development.

This is why Disney added a disclaimer in front of the film on their streaming platform. But on the remake released in 2019, the whole sequence with the crows was removed from the script.

Children’s books require a different approach. They are not only consumed by children but hold a special nostalgic place in the heart of the adults who read them. But throughout the years, it has been common practice to change and update these works so they can still impact a new generation.

In 2021, the estate of Dr Seuss decided to cease the publication of six books deemed too hurtful and racist.

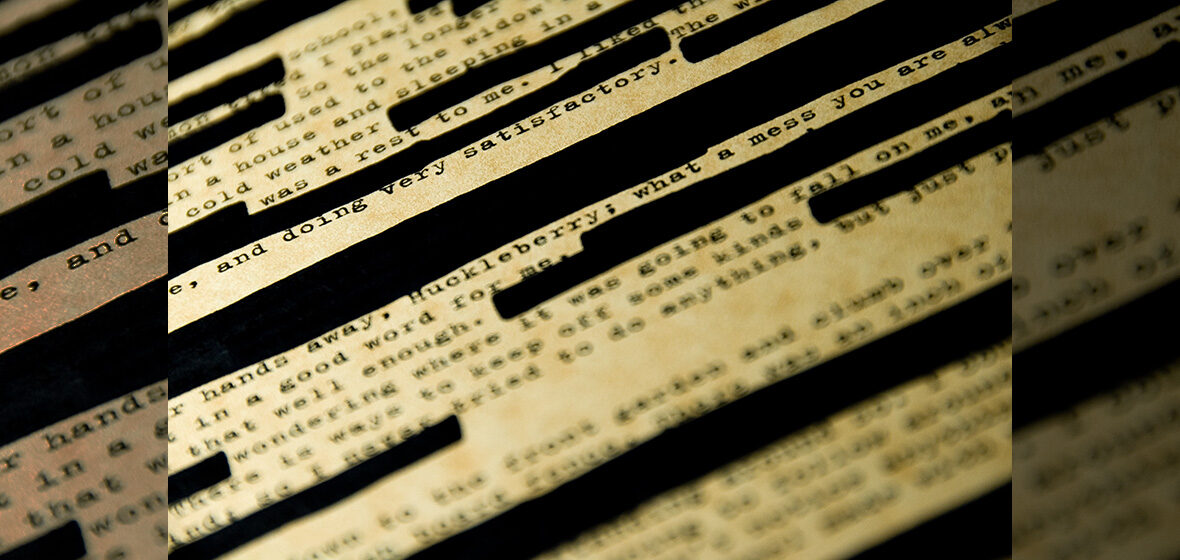

Over ten years ago, the publisher of Mark Twain’s novels removed the offensive racial slurs from the texts.

And Roald Dahl agreed to edit his work when he accepted a request from the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) to replace Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’s Oompa Loompas, who were portrayed initially as African Pygmies.

It’s a standard process but not exclusive to children’s literature.

The Big Friendly Bigot

Salman Rushdie’s reaction refers to Dahl’s controversial character. While a beloved and decorated author, Dahl was extensively criticised for his open antisemitic views. Dahl made public comments outside his books and perpetuated offensive Jewish tropes about media and world domination. In 2019, his estate apologised for the nasty comments.

But while that doesn’t come through explicitly in his works, there is a grave nastiness to his characters that, even at the time, other beloved authors criticised him for.

Maurice Sendak, the author of Where the Wild Things Are, said, “the cruelty of his books is off-putting”, and Earthsea writer Ursula K. Le Guin commented that “there’s a cruel streak to Roald Dahl”.

“One of my daughters was very fond of his earlier books. I was very happy when she outgrew him, I have to say. There’s something a little gross and a little cruel in his work,” Guin said.

A Time Magazine profile revealed that some of Dahl’s most famous works had to be edited before publication for his offensive portrayals. The BFG included a drawing of the Giant in the tradition of black minstrel shows, which prompted the comment from the editors that it was “a derisive stereotype”, to which Dahl replied, “the negro lips thing is taken care of”.

Stephen Roxburgh, who edited most of Dahl’s books, had a hand in removing many offensive remarks in the original texts. In a text published for Publishers Weekly, Roxburgh reminisced about his time working with Dahl, particularly the experience with The Witches.

In one of Roxburgh’s notes, he shows concern about the portrayal of women, with which Dahl disagrees.

This portrayal of women in The Witches is addressed in the new 2023 changes. Dahl’s description may seem harmful, but even before it was edited it was being flagged by his editors as a point of concern.

The new inversion includes that extra note that tries not to demonise people with wigs. In retrospect, it makes sense without removing elements from the story.

But its importance is better summarised by a Billy Bragg tweet. The British singer-songwriter made headlines in 2021 when he decided to change the lyrics of his song ‘Sexuality’ in an effort for them to be more inclusive. “Although music cannot change the world – it has no agency – it can change your perspective and challenge your prejudices,” he said.

If a song, why not a book? Bragg wrote about the changes to Dahl’s book, specifically the line about bald women: “Suppose your mom wears a hairpiece because of chemotherapy and the kids in her class call her a witch because they read in Dahl’s book that all witches wear wigs”.

Like in Australia, copyright laws in the UK include the protection of “moral rights” that protect the personal relationship between a creator and his creation when they don’t own the copyright of the work anymore.

Included in the Copyright Act 1968, it’s a right that can’t be relinquished or sold. Instead, it is inherited by a personal representative or estate upon the creator’s death. It’s a way to protect the integrity of the work, even after its creator has passed, by putting the onus of that responsibility on those related to them.

So something like this can still happen in the future in Australia. In 30 years, we can discuss the author’s intent again when Mem Fox’s estate decides that the lamington plate is now in a bakery in Hobart instead of a casino.