“A conviction is very damaging to future employment prospects. For addicts, the last thing you want to do is scar them for life in terms of future employment, earnings, travel.”

The war on drugs hasn’t worked and it’s time to change our approach, say experts. In NSW, where community attitudes have been shifting over the past decade, research shows increasing support for treating illicit drug use as a health issue rather than a criminal justice problem. Is it time to consider reform?

She was the golden girl of her middle-class family. University medallist, student of medicine, the recipient of a doctorate in clinical psychology. Few could have guessed Emily* – a pseudonym she goes by to protect herself from the stigma of a criminal conviction under her former name – would succumb to heroin or crystal methamphetamine (ice).

“No one thinks it will happen to them. No one thinks, ‘I’m going to start using to intentionally f*ck up my life,’” she tells LSJ.

Emily is sharing her story on an anniversary of sorts. It’s the 7th of September, exactly three years since she first went to jail. Police raided her social housing apartment to find a stash of heroin, and she was convicted of deemed supply (three or more grams of heroin is “deemed” to be supplying other users).

But it wasn’t prison that changed her life irreversibly and forced her to bury her former identify in favour of a pseudonym. That happened six years ago, in 2015, when she received her first criminal conviction for drug possession.

She was leaving court on a good behaviour bond when a newspaper photographer snapped her. The next day, her photo was splashed across the crime pages, publicising her fall from grace. The article revealed details from Emily’s hearing including that, just two years earlier, she had become a prostitute and was caught stealing letters from mailboxes to find cash to pay for ice.

“Before that [court appearance], I had no crime or legal issues. I had never spoken to a cop,” she says.

“Within a month after trying ice for the first time, I was arrested for the first time. My landlady, who had known me for 11 years as a nice normal, clean girl, saw my photograph in the paper and asked me to leave. I became homeless. Everything went to sh*t at a really fast pace.”

In her 20s, Emily had sought treatment to successfully kick a heroin addiction, and she had remained clean from drugs throughout her 30s. When she relapsed and was caught with ice at 41, she lost her career in psychology, her eastern suburbs Sydney apartment lease, and was later evicted from social housing. Now 49, she drifts between homelessness and women’s refuges. She is on a doctor-prescribed methadone program, but often the urge to use heroin and ice is too strong. She reveals she has used in the past two days.

“All the anti-drug TV advertisements are so easy to dismiss as someone other than yourself,” she says. “They show people with no teeth and scabs all over their arms and their faces. Everyone thinks, ‘Oh, that won’t happen to me. That’ll never happen to me. I just smoke ice occasionally, when I’m tired at work.’

“The thing is, you don’t have to go all the way to scabs and no teeth for your life to be devastated.”

Addiction in the system

Although Emily’s story made headlines for a day, it is not unique to local courts.

Data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) shows illicit drug offences were the third most common principal offence among defendants finalised in magistrate’s courts across Australia between 2019-20. Almost 45,000 defendants faced courts on drugs charges that year. Of those, more than two thirds of defendants were charged with possession or use offences. Meaning: most were caught with relatively small amounts of drugs – not enough to be trafficking or supplying other users.

Many defendants found guilty of drug possession in NSW will escape prison. Magistrates often let first-timers off with an informal warning; by dismissing the charges under Section 10 of the Crimes Act, which sends them home without a criminal conviction on a good behaviour bond. But dismissal is not guaranteed: the maximum legislated penalty for possession in NSW is two years in prison. And when addicts like Emily return to court multiple times, or are caught using drugs again, they often wind up behind bars anyway.

“Jail just hits the pause button,” Emily says. “It was a very abrupt pause button, and I managed to stay off heroin and ice but there are other drugs in jail. There’s a whole economy of needles that get shared around … I can’t see much rehabilitation value in terms of prisons.”

According to the AIHW, more than three-quarters (78 per cent) of police detainees who provided a urine sample in 2019 tested positive for at least one type of illicit drug. In contrast, rates of drug use among the general population were substantially lower, with 1 in 6 (16.4 per cent) people aged 14 and over reporting the use of any illicit drug in the past 12 months.

Tim Leach, the director of Community Legal Centres (CLC) NSW, speaks on behalf of CLC lawyers when he tells LSJ, “we think drug use needs to be considered a health issue rather than a criminal justice issue”.

“The current laws undermine a public health response to drug use and treatment,” he continues. “They cost a lot of money to enforce, they’re not effective, they push people who aren’t criminals into the criminal justice system. They push young people into the justice system when that serves no purpose and we know the consequences can be very negative.”

According to the Productivity Commission, the annual cost of prisons in Australia reached more than $4.6 billion in 2017-18. This equates to $302 per prisoner per day. In comparison, a study by Deloitte in 2012 found diverting drug offenders into residential treatment costs between $200-$280 per client per day. The report found treatment also significantly improved mortality and quality of life, resulting in total estimated public savings of $111,548 per offender.

Leach explains that a criminal conviction shows up on background checks in many job applications. It puts a professional career out of reach for former drug offenders, and prevents them travelling overseas to countries that do background checks on travellers, like the US and Canada. Leach says these impacts can be serious and lifelong for young people caught experimenting. For addicts, they impede recovery and intensify social stigma by labelling them criminals.

Shifting community attitudes

Stories like Emily’s add to a growing body of research linking drug addiction with criminal recidivism and provide the backdrop to changing perceptions about how we deal with drug use in the justice system. Lawyers, judges, and cabinet ministers alike are at loggerheads as to how we should treat addicts who are weighing on police and local court resources with repeat possession offences.

The discussion revolves specifically around possession; being caught with a small quantity deemed only for personal use. Quantities vary between state and federal jurisdictions but in NSW, less than three grams of heroin, ice or cocaine is considered a “small quantity” for a possession offence. Most groups agree we should continue to clamp down hard on larger-quantity offences of trafficking and supplying drugs.

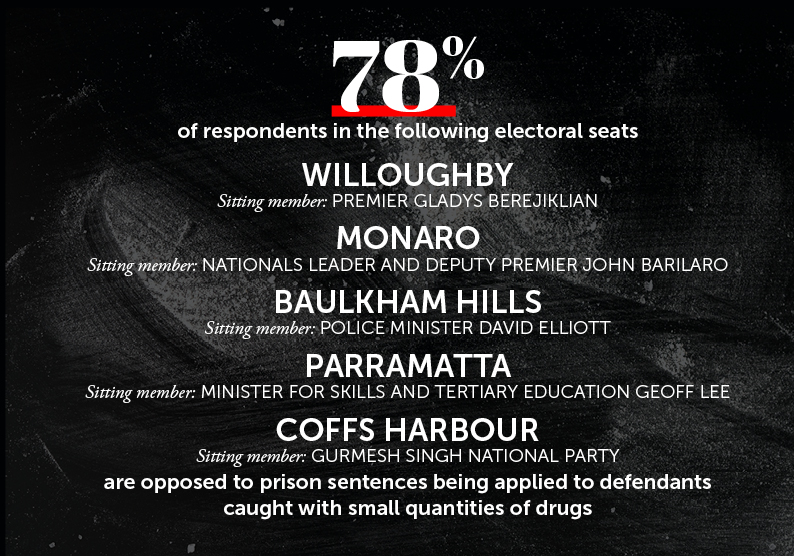

A study by Uniting Church published in September recently polled five traditionally conservative electorates held by government members who have previously rejected calls to decriminalise or “de-penalise” possession of drugs. They were Willoughby (Premier Gladys Berejiklian’s seat), Monaro (held by Nationals leader and Deputy Premier John Barilaro), Baulkham Hills (Police Minister David Elliott), Parramatta and Coffs Harbour. The phone survey polled more than 3200 people, finding the majority – more than 78 per cent of respondents – were opposed to criminal sanctions being applied to defendants caught with small quantities of drugs.

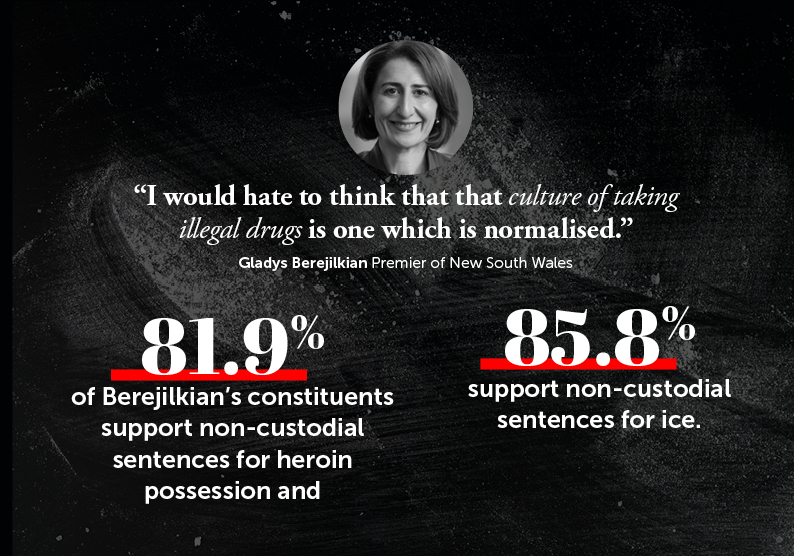

Among Berejilkian’s constituents, 81.9 per cent supported non-custodial sentences for heroin possession and 85.8 per cent supported non-custodial sentences for ice. This is despite the Premier previously stating she is firmly opposed to easing her tough stance on drugs. She ruled out the possibility of decriminalisation after her government’s 15-month Special Commission of Inquiry Into the Drug “Ice” recommended it. She has also long resisted calls to introduce pill-testing at music festivals, telling media in 2018 that, “I would hate to think that that culture of taking illegal drugs is one which is normalised and one where pill testing is seen to be the absolute end to fixing this problem.”

Emma Maiden, the Head of Advocacy and Media at Uniting and a former employment relations lawyer, says her organisation was inspired to conduct the research after government leaders rejected previous attempts to discuss drug law reform.

“The most recent National Drug Strategy Household Survey in 2019 showed there was 68 per cent support among Australians for non-custodial options – rather than sending people to prison caught with small amounts of drugs,” she says.

“But when we meet with MPs to talk about drug law reform, they tend to say, ‘That might be what the national survey shows, but that is not what people think in my electorate.’ We [Uniting] really wanted to test that hypothesis.”

Former Director of the Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) Don Weatherburn says he has watched community attitudes towards drugs change over almost three decades of examining the data. Weatherburn, who in 2019 became a professor at the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (NDARC) at UNSW, once might have believed prisons to be the correct place for drug offenders – but his work at BOCSAR transformed his thinking.

“I didn’t always hold this view. I formed it by watching the evidence roll in. When the facts change, you change your mind. It became clearer and clearer that prison was not a deterrent to drug users,” he says. “How do I know this? There are endless studies of arresting drug-dependant people and putting them in prison.”

One of those recent studies was conducted by BOCSAR alongside NDARC and published in September 2020. It showed treating offenders with rehabilitation through the NSW Drug Court program – which sentences defendants involved in drug-related offences to rehabilitation and medical treatment rather than prison – was far more effective than sending them to prison. Drug Court participants were found to have a 17 per cent lower reoffending rate than those not placed in the program. Participants also took 22 per cent longer to commit assault or an “offence against the person”.

Weatherburn shows LSJ some of his latest work: yet-to-be-published research drawing data from the 2013, 2016 and 2019 National Drug Strategy Household Surveys. It reveals Australians’ support for cautions, warnings and treatment for drug use has grown – particularly for cannabis and ecstasy possession. Only 3.7 per cent of respondents in 2019 believed possession of cannabis should send a person to prison. About 20 per cent of people believed prison was the correct place for people caught possessing ice or heroin – but there was increased support for education and treatment of drug addiction as alternatives.

“A conviction is very damaging to future employment prospects. For addicts, the last thing you want to do is scar them for life in terms of future employment, earnings, travel,” he says. “I think the public is coming around to that view. They hear public debate, some stick to their guns, but some listen. Some might see stupid things that kids do and they aren’t going to repeat. A big proportion of the current generation have smoked dope, and that has an impact on attitudes.”

A new approach

NSW Attorney-General Mark Speakman responds to the results of the Uniting Survey with an attitude that might once have been considered progressive. In September, he told local newspaper The Leader that the current criminal justice response to illicit drug use “is not working”. In an interview with LSJ on the issue, he says, “the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results”.

“Looking at court diversion or pre-court diversion is not being soft on crime. It’s about addressing the underlying health causes, and ultimately reducing reoffending.”

Speakman emphasises decriminalisation is off the table because “we want to make sure that we’re not normalising drug use”. However, he reveals his government is considering other alternatives.

“We’re considering the recommendations [from the ice inquiry]. There are a whole lot of different permutations and combinations you can have in diversion. In NSW, at the moment, we have a diversion scheme for drug possession at music festivals. A criminal infringement notice is issued to the person in possession, and they pay a $400 fine. If the fine is paid, they don’t get a criminal record.

Don Weatherburn

Don Weatherburn

“What we don’t want to do is focus on punishing people for being drug users, rather than trying to help them with a health response. At the end of the day, this is a health issue, not a criminal justice issue.”

It’s an approach that might have helped recovered heroin addict Kevin Street access treatment decades earlier. Street, 65, became an advocate for Uniting’s “Fair Treatment” campaign after getting clean from a 35-year addiction.

“Funnily enough, I had my first injection of heroin in jail, while on remand,” he says. “People are shocked at that … When I was released from prison after my trial, I was able to seek it out on a daily basis because I liked the way it made me feel.

“I didn’t know it at the time but when I started using [heroin] I was probably medicating for post-traumatic stress syndrome. Dealing with sexual assault because I grew up in child welfare institutions in NSW.”

Street reached a turning point when he started taking his heroin at Sydney’s Medically Supervised Injecting Centre, which is run by Uniting and staffed by professional doctors who talk to users about treatment options. Doctors there convinced him to try a buprenorphine treatment program and booked him for counselling regarding the underlying mental health issues he had carried since childhood. After 2659 visits – he has kept all his patient notes – Street got clean.

“For so long, the stigma of being called a criminal and an addict made me too scared to ask somebody for help,” he says.

“A much better way to approach this would be to start talking about decriminalisation, to remove some of the stigma around drug use. We should treat it as a health issue than a criminal issue – if you come into contact with the police, you’re referred on to health services rather than the courts.”

Lawyers’ attitudes

The legal community has broadly supported diversionary measures for drug possession crimes when the issue has come up in recent years. As many as 60 organisations, including the NSW Bar Association, voiced support in 2018 for Uniting’s Fair Treatment campaign, to have illegal substances decriminalised for personal use. At the time, a report by the Penington Institute showed annual drug deaths had almost doubled in the decade to 2016, with 142 people in Australia dying every month from accidental overdoses.

Law Society of NSW President Juliana Warner says her organisation is in favour of diversionary measures.

“It is the Law Society’s long held position that diversionary measures are generally a more effective alternative to imprisonment in reducing recidivism in drug and alcohol related, as well as other, offences,” she says. “This view is backed by a number of studies conducted by the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR).”

President Warner notes the Law Society has made “extensive submissions to a number of inquiries, including the Ice Inquiry”, and already supports existing diversionary systems including the Drug Court and Magistrates Early Referral into Treatment (MERIT) program. She says continuing to shift the focus on drug use from a law enforcement problem to a health issue “will require a commitment from the NSW Government to substantially increase resources to improve services and support drug users”.

“The Law Society looks forward to the NSW Government’s final response to the remaining recommendations from the Ice Inquiry and continuing to engage with the Government on the practical implementation of the recommendations and any subsequent legislative changes.”

*name has been changed to protect anonymity