A novel based on real events, characters and crimes offers a challenging perspective on life behind bars, and its author highlights the need for changes to Australia’s criminal justice system.

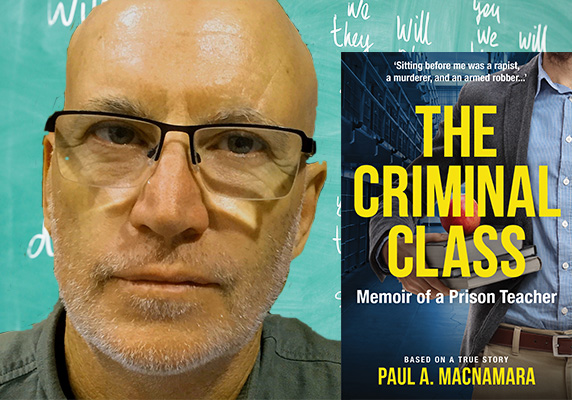

Shining a light on the prison system has created a welcome reception for The Criminal Class: Memoir of a Prison Teacher from both the public and publishing industry alike. This novel, based on the author’s experience of teaching in a prison, has been nominated for the Australian Crime Writers Association’s 2023 Ned Kelly Awards in the category of Best Debut Crime Fiction and also for the Queensland Literary Awards in the category of The University of Queensland’s 2023 Fiction Book Award. It is an impressive feat for the first-time published author, who has had no formal training as a writer.

Working in the prison system was never Paul MacNamara’s intention. The ESL teacher was halfway through responding to a newspaper advertisement seeking an adult education officer when he discovered the posting was at Sydney’s Silverwater Correctional Complex.

“I just thought I’d give it a try and see what panned out from it,” MacNamara explains.

In his first class, MacNamara counted murder, rape, armed robbery and grievous bodily harm among the charges against his students, all of whom were sitting just three metres away. A distress alarm hung by the only door in the room, while sharpened pencils or “potential weapons” perched on each table. MacNamara recalls feeling a bead of sweat rolling down his chest.

“Prisons are one of the few places still left where the more violent you are, the more rewarded you are in terms of status,” he says.

Not long before MacNamara started at Silverwater, the author says, “a guard was seriously attacked and he subsequently died. So when I first arrived, the [atmosphere] was heightened. There’s a pervading sense that at any time, the whole thing could become chaotic. In that classroom situation, you’re outnumbered, and if [the prisoners] wanted to, it could get really ugly.

“I tried to have a coolness to my approach, as if it was just another day at school. Soon after, you realise the needs of the students, you get into teacher mode and things become more normal again.”

This anecdote opens MacNamara’s debut title, a fictionalised account of the six and a half years the author spent working as a numeracy and literacy teacher in correctional facilities across NSW. It’s one of several entertaining, thought-provoking and heartbreaking stories that offer a unique perspective on life behind bars – one that is independent of the viewpoint of both law enforcement and lawbreakers.

While fiction, the characters, events and crimes depicted in the novel are based on true stories. The protagonist Tommy, a newly-appointed teacher, guides readers through The Criminal Class, which spans his first day on the job to the prison being decommissioned. Each chapter also features self-contained stories and first-hand accounts of actual crimes, from drug dealing and theft to battery and assault.

Several overarching themes, including class, race, sexuality and justice, help to unify the novel, but it is the strong portrayal of the characters and descriptive insights into their circumstances that create the deepest impression on readers. This is perhaps not surprising given the relationships the author formed with his students over the course of his prison teaching career.

In several instances, MacNamara begins with the backstory of the character, emphasising who they were and how they behaved in society, before introducing the prison setting following the crime. This juxtaposition helps to emphasise the often tragic and complex causes of imprisonment. As MacNamara says, “most prisoners I encountered were not innately evil. Most came from lower socio-economic backgrounds and the majority were recidivists.”

From an older prisoner who had frequented jail throughout his life not being able to read the daily news, to an inmate who could not understand an analogue clock and was reprimanded for being late to class, MacNamara found “the low levels of literacy and numeracy in the general prison population [to be] extraordinary”.

But while many prisoners “had genuine needs” and a keen interest in learning to read, write and become more job ready, MacNamara says the politics of the prison system complicated the future for inmates. For example, when students who held prison industry roles prioritised their education, MacNamara would receive complaints from their supervisors about stealing their workers away.

‘The low levels of literacy and numeracy in the general prison population were extraordinary.’

But while many prisoners “had genuine needs” and a keen interest in learning to read, write and become more job ready, MacNamara says the politics of the prison system complicated the future for inmates. For example, when students who held prison industry roles prioritised their education, MacNamara would receive complaints from their supervisors about stealing their workers away.

Exposing these organisational tensions is a factor in the author’s advocacy for change within Australia’s criminal justice system, with the book used as a vessel to stimulate critical conversations about issues, including the high recidivism rate, costs to taxpayers pf the prison susyem, and the perplexing nature of legal proceedings.

“People who are currently in the [prison] industry said the book was a really authentic representation of the system, and sadly someone said to me, ‘if you thought it was bad then, you should see it now’,” he says.

“Some people do terrible things and I can understand the idea of locking them up and throwing away the key. But when you explore the backgrounds of certain people, I think about if I were in that situation and where I would have ended up.

“Is the system doing the best it can in this day and age or should it be reformed? Just opening up that question with people, especially taxpayers who are paying for the system, is a key takeaway for me.”

According to the Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services 2023, 42.7 per cent of Australian adult offenders returned to prison within two years of leaving, a figure that increases to 51.5 per cent when also including community corrections. Overall, this rate is higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people than non-Indigenous people, across all states and territories.

The latest report shows that 42.7 per cent of Australian adult offenders returned to prison within two years of leaving, a figure that increases to 51.5 per cent when also including community corrections.

While MacNamara admits he is not “an advocate for releasing everybody”, he believes the community is responsible for reflecting on these high statistics.

“In the six and a half years that I was [working in prison], I would see the same people coming back. As a society, do we think that is a good business model to have, that many people returning? And if not, is there a better way to do that? I’m not an expert and I don’t have the answers, but I think they are questions worth asking.”

It is a particularly poignant reflection when considering the increasing cost of Australia’s criminal justice sector, which was almost $22 billion in 2022, a rise of 3.4 per cent from the previous year. Funding for police services was the largest contributor to this figure (64.5 per cent), followed by corrective services (26.2 per cent) and the courts (9.2 per cent), according to the same Productivity Commission report.

The legal system’s “extraordinary cost” was striking for MacNamara, who notes the financial impact on the prisoners themselves, recalling some using their houses as collateral for their appeals. He was also shocked by the complex language and legal jargon used in court proceedings, particularly as he understood first-hand the poor literacy levels of many prisoners.

“Occasionally I was used as an independent witness in case conferences,” he reflects. “I remember this one case involving a student in my class. I knew how limited his reading and writing were. When the guard was explaining what was happening and asking him to sign a document, which he agreed to, it was all in legalese. I don’t think I actually fully understood what was said, and I knew for sure that he had no idea. The whole law is almost like another foreign language.”

MacNamara concludes: “I knew jails weren’t ideal, but I went in there without any preconceptions. I think the book just gives people an authentic look of what actually does happen – the good things, the bad things, the terrible things, the funny things.”