From the trenches of Gallipoli to settling civilian claims against the Australian Imperial Force on the Western Front, one Sydney lawyer’s military career did not unfold the way he thought it would. On the eve of Anzac Day, LSJ speaks to military historian Tony Cunneen about a man who would become a pioneer among the earliest lawyers in the WWI military forces.

Before the internet age, looking into the past involved sifting through archive boxes housed in libraries. When Tony Cunneen embarked on a project for the Francis Forbes Society for Australian Legal History, it was this kind of careful artefact handling that was necessary before a more complete picture of the person he was researching could be assembled.

In the case of Colonel Arthur Wellesley Hyman OBE (1880-1947), a solicitor from Sydney’s Neutral Bay, a trove of diaries and other materials was stored in the Mitchell Library. Cunneen, a teacher at St Pius X College in Chatswood, recalls finding Hyman’s original papers – still brushed with the mud of Gallipoli in ANZAC Cove – with exhilaration.

“When I went to the library, all these items came out of a box,” he says. “Arthur kept everything. He was a real bowerbird. Australian soldiers used to get packages of comfort from children, and he’d keep the little messages. One message said: ‘To the soldier who opens this package, I hope you have a nice day.’

“He was clearly an emotional and committed man, and his diaries [reflect] someone who was [both] passionate to go away and desperately homesick … He would often write, ‘I can’t function properly, I’m missing Zara and the children so much’.”

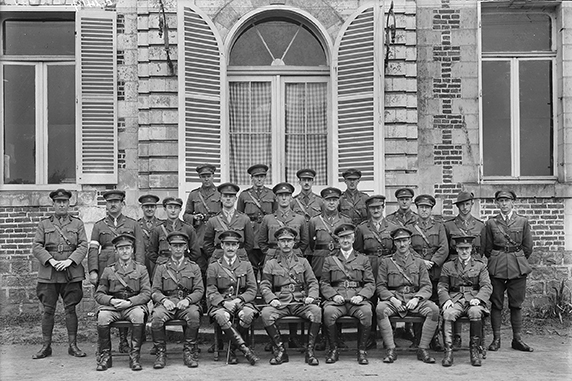

Towards the end of the First World War, Hyman was named an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) at the rank of Major for “continuous good service and devotion to duty as Divisional Claims Officer”. His award was endorsed by Major-General Ewen Sinclair-Maclagan, who described Hyman, of the 51st Battalion AIF, as an officer well worthy of recognition.

“This officer is most conscientious in the performance of his duties, always having the welfare of the Division at heart while investigating claims and, at the same time, safe-guarding the interests of French claimants and the British Government,” the Major-General wrote.

For a man originally of the 7th Light Horse Regiment and who Cunneen suspects was not the best horse-rider, Hyman would go on to have a notable military career. The Tamworth-born 34-year-old was moved from unit to unit (Cunneen suggests this was due to his advanced years), serving abroad for five years and, for a time, on the staff of General Sir John Monash.

“Before Hyman enlisted he was a member of the Light Horse Militia … But I don’t think he was very good rider. He had trouble on horses, he fell off a few times,” Cunneen laughs.

“He may have been a well-placed solicitor, but he wasn’t quite the outback heroic type they were expecting.”

In WWI, Hyman served as a frontline lieutenant with the 7th Light Horse Regiment and was transferred to Turkey in May of 1915. Four bloody and challenging months later he was sent to Malta suffering a terrible case of dysentery, and then transferred on to London. By the time he recovered, the Imperial Forces had withdrawn from Gallipoli, but Hyman’s return coincided with a growing need for skilled solicitors to help administrate the complexity of military law. While Hyman may not have been the best rider, he had fastidious legal skills and attention to detail.

“As the war progressed, legal skills became more in demand. The AIF reached a stage where they would go around and try to find out who were lawyers in the army,” Cunneen says.

“Of course, that was the last thing people wanted to do. They didn’t join the army to be lawyers. They wanted to join the army to fight. They were very passionately loyal to Australia and the Empire. The Empire was a sacred bond of nations and they were going to prove themselves as equal members of that empire.”

The story of claims officers is one of those wonderful, untold aspects of WWI that the legal profession was in and nobody really knows about it.

TONY CUNNEEN

In Egypt, Hyman served on a number of military courts and then sailed to Marseilles in France. From there, he travelled north by train, following a picturesque route through Europe where many other Australian soldiers shared the magical experience of travelling through vistas taken straight from the pages of their school history books – green fields, snow-capped mountains and cathedrals floating on distant horizons as they went along.

“Often for the Australian soldiers it was a remarkably compelling experience. They had no idea what was to come, of course. They thought they would defeat the Germans almost single-handedly,” Cunneen says.

“Hyman was a part of that, but I don’t think he saw any frontline action. He was very soon seconded and went on to become what was known as a claims officer. The story of claims officers is one of those wonderful, untold aspects of WWI that the legal profession was in and nobody really knows about it.”

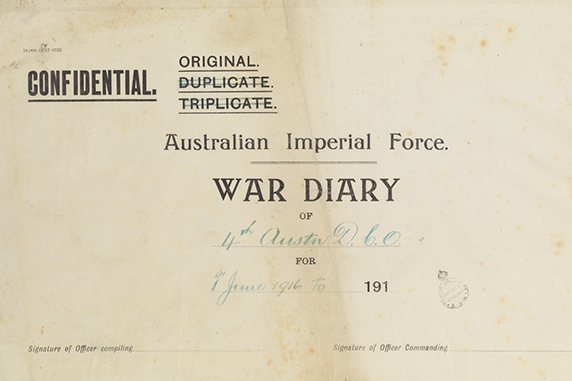

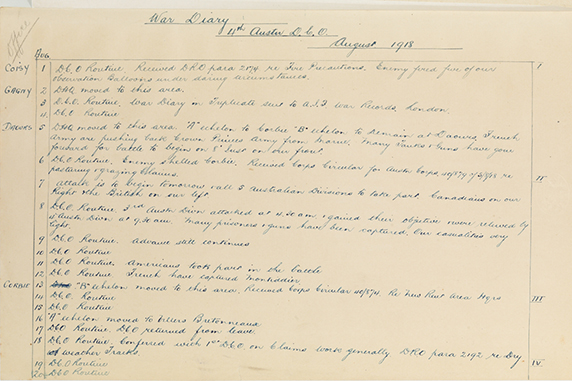

And so Hyman was transferred to take up a post as a divisional claims officer (DCO) in mid-1916. By November of that year, Hyman was made President of all Field General Courts Martial in the 4th Australian Division and presided over courts dealing with hundreds of cases involving non-commissioned officers and soldiers. According to the book Justice in Arms: Military Lawyers in the Australian Army’s First Hundred Years, the majority of charges were for desertion, absence without leave, drunkenness, disobedience, and conduct or acts to the prejudice of good order and military discipline. Some other cases involved insubordination and ‘when in arrest, escaping’.

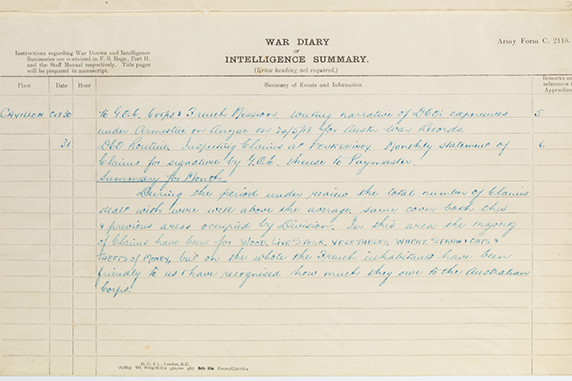

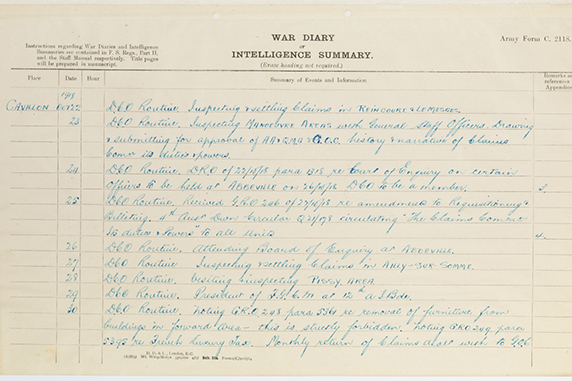

Claims officers would move around with the troops of the division they were attached to, Cunneen says, and Hyman (who distributed well over one million Swiss Francs during his time in the role) would investigate with the assistance of an interpreter about 30 claims in a few days by riding around on a bike. As a claims officer for the 4th Division in France and Belgium, he had to inspect and adjudicate on the worth of claims from local civilians as to damage to property and determine whether compensation should be paid. The property included everything from felled trees to missing poultry.

“I feel it would have been difficult for the soldiers to have been under artillery fire and then have to ask permission [to] dig a hole. It was ridiculous. You need to recognise that sometimes things can get quite out of hand. Someone had to go in the next day and sort it out,” Cunneen says.

The situation facing the soldiers in these foreign villages was complex. It was imperative to have a system of redress, facilitated by claims officers like Hyman, who could mediate disputes and compensate parties where necessary.

Hyman’s own notes recount that, when court martials in the field were held a mile or two from the fighting, occasionally he had to adjourn a court until the enemy’s shelling had ceased.

In WWII, Hyman served as a legal staff officer with the 1st Cavalry Division and went on to lead as President of the Jewish Historical Society and a trustee of the War Veterans’ Home, the Anzac Memorial, and the NSW Jewish War Memorial. He later attained the rank of Colonel with the Army Legal Corps.

As a Gallipoli veteran, Hyman was considered a “genuine soldier” and was able to wield influence and authority that allowed him to move between the civilian and military worlds with ease.

“Hyman was a well-respected solicitor,” Cunneen says.

“He was obviously an articulate, forceful personality.”

Hyman resumed practice as a solicitor in Sydney and joined the partnership of Bradley, Son, Maughan, Hyman & Kirkpatrick in 1930.

He died in Edgecliff in December 1947, aged 66.