“The people I am bringing voice to in this place, are very concerned that our flag has been colonised given this is the colonisers’ headquarters and they’ve just purchased our flag”

The Federal Government recently announced it had “freed” the Aboriginal flag for all Australians to use without fear of copyright infringement. Some people are celebrating the news, while others are disappointed. Here's why.

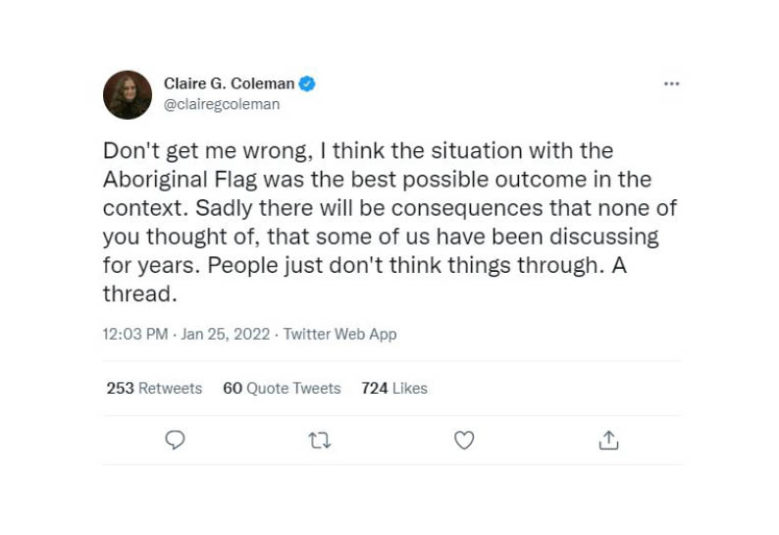

Two days before Australia Day in January 2022, the Australian Federal Government announced it had “freed” the Aboriginal flag for all Australians.

In legal terms, the government had struck a $20 million deal to take over the copyright of the Aboriginal flag design from original creator, Luritja artist Harold Thomas. With the copyright now under Commonwealth control, the government promised all Australians would be able to replicate the flag design on sports apparel, websites, in paintings, artworks and in any other medium without fearing legal action for copyright violations. Many Australians celebrated the Prime Minister’s announcement. Others are sceptical.

The genesis of the #freetheflag campaign

Thomas, an activist from Luritja lands around Alice Springs, originally designed the Aboriginal flag to lead a demonstration in Adelaide in 1971 during what is now NAIDOC (National Aboriginal and Islander Day Observance Committee) Week. The iconic red, black, and yellow design has since become a symbol of resistance and unity for Indigenous Australians.

The design became so ubiquitous it’s fair to say many Australians had not considered that copyright might apply to it. The flag has appeared on many iconic occasions: flying at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy protest in Canberra in 1972, wrapped around the shoulders of 400m sprinter Cathy Freeman when she embarked on a victory lap after claiming gold in the Sydney 2000 Olympics, printed on sports team jerseys during Indigenous playing rounds.

But copyright law automatically applies to creators of original artistic works – including flag designs – for the life of the author and 70 years thereafter. The Copyright Act 1968 prevents others from copying or communicating the author’s material without their permission.

“I do think people assume it is a national flag and they wonder, how can somebody can assert ownership of it?” said Terri Janke, a Wuthathi/Meriam woman and intellectual property lawyer. Janke has practised in intellectual property rights for almost 30 years and is considered an international authority on Indigenous cultural and intellectual property rights.

“People get confused as to whether you are allowed to display the flag or march with the flag – you could always do those things. But the reproduction rights are what have been under question.”

Greens Senator and DjabWurrung Gunnai Gunditjmara woman Lidia Thorpe

Greens Senator and DjabWurrung Gunnai Gunditjmara woman Lidia Thorpe

Thomas established a licensing agreement with Australian flag manufacturer Flagworld in the mid-1980s, giving the company exclusive use of the copyright to make and sell flags bearing the design. He also sold exclusive rights for using the design on clothing to non-Indigenous fashion label WAM Clothing. It meant when Indigenous social enterprise Clothing the Gap began putting the flag on its clothing, WAM slapped the organisation with a “cease and desist” letter – threatening legal action if Clothing the Gap did not sell all flag stock within three days. It also issued notices to organisations like the AFL and NRL for using the flag design on player jerseys during Indigenous football rounds, and to small Aboriginal community groups including charities and health organisations.

In response, Clothing the Gap started an online campaign to “free the flag” from copyright laws. A petition quickly drew nearly 50,000 signatures of support and put the issue in front of media and government to consider over the following two years.

“This is a question of control,” the petition read. “Should WAM Clothing, a non-indigenous business, hold the monopoly in a market to profit off Aboriginal peoples’ identity and love for ‘their’ flag?”

The Commonwealth now ‘owns’ copyright – is that a good thing?

In September 2020, the Federal Senate set up a parliamentary inquiry to look at options to “enable the flag to be freely used by the Australian community”. The upshot of its final report was a recommendation to negotiate with Thomas to acquire the copyright of the Aboriginal flag – which the Federal Government eventually did in January 2022. It was revealed in Senate estimates in February that Thomas received $13.75 million while WAM Clothing received $5.2 million.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison was quoted in a press release on 25 January saying: “All Australians can now put the Aboriginal Flag on apparel such as sports jerseys and shirts, it can be painted on sports grounds, included on websites, in paintings and other artworks, used digitally and in any other medium without having to ask for permission or pay a fee.”

But not everyone welcomed the news. Greens Senator and DjabWurrung Gunnai Gunditjmara woman Lidia Thorpe accused the government of “colonising” and “assimilating” the Aboriginal flag.

“The people I am bringing voice to in this place, are very concerned that our flag has been colonised given this is the colonisers’ headquarters and they’ve just purchased our flag,” Senator Thorpe said in Senate estimates on 18 February.

Indigenous author, artist and Gunai woman Kirli Saunders said she was excited the flag had been released from copyright restrictions, however, she had strong reservations about the new owner of copyright.

“What’s worth noting is that the copyright for that flag now belongs to the same settler colonial government who have harmed our communities immeasurably,” she wrote in a post on her Instagram page.

“I don’t think we can talk about the flag being freed or celebrate freedom while there is no treaty, no government recognition of our sovereignty and no voice to parliament.”

Janke told LSJ the difficulty with Australian copyright law is that copyright cannot be handed over to a non-specific group of people. It must be owned by a person or a legal entity.

“I can see they [Thomas and the government] had this problem – what entity should own the copyright? Because copyright has to be owned by someone. There is no national independent Indigenous legal entity [that is not partially funded by government] that could own it at the moment,” she explained.

“We are now in a place where people don’t have to get permission from Harold [Thomas] or the licensee to use the design, other people can reproduce it. The football teams that wanted to use it on jerseys, schools that wanted to use it as part of their Indigenous activities for NAIDOC Week, those sorts of things. I think it’s a good thing that people can do that and not be in fear of a copyright infringement action.

“But I’m aware it does hand the ownership of the flag to the Commonwealth, which is like the colonial power owning the colonised flag.”

A broader issue for Indigenous intellectual and cultural property

Janke said she hoped the Commonwealth’s acquisition of copyright was a first step towards placing the flag design under Aboriginal control.

“I’m hoping we’re on a road to something more … I note the recommendations of the Senate inquiry was that the flag should be Indigenous owned and controlled,” she said.

She said she hoped the situation had opened the eyes of the public as to how copyright laws work and may shed light on the broader problem of Indigenous cultural property being used without permission from the copyright owners.

“If you go shopping in any of those souvenir markets, it’s evident that probably 80 per cent of what you find is not authentic. There are all sorts of appropriations in the fashion industry that are using Aboriginal art,” she said.

“The Aboriginal arts movement in Australia is one of the biggest in the world. But you see these rip-offs coming in and it harms on two levels. There’s the cultural harm – people are copying artworks that come from country and tell stories of place that Aboriginal people are sharing to educate. It’s their iconography and just copying it demeans their cultural practice.

“And then the other harm is the economic harm that these rip-offs cause to Aboriginal art centres, Aboriginal artists. It’s very hard for those visual arts industries to be strong and enforce their rights because they don’t often have the money to take action for copyright infringement.”