Cheryl Grossmann is a court stenographer with over 38 years of experience in every jurisdiction in South Australian courts, as well as Federal jurisdictions, mediations, Royal Commissions and government hearings. Grossmann shares her insights.

What does the role of a court stenographer entail?

We’re there to provide a high-quality, accurate, verbatim record of court proceedings. We also need to conform to client requests, style guidelines and service level agreements. Most of my work is real time, so I provide a transcript you can see as it’s happening in court. It enables instant access to the transcript which counsel and the judges can view, search and annotate. We work under pressure in different environments and jurisdictions and there’s often a high degree of confidentiality. A speed of 225 words a minute is required to cope with the pace. We also need a good command of English grammar, general knowledge, common Latin phrases that are used, and legal terminology.

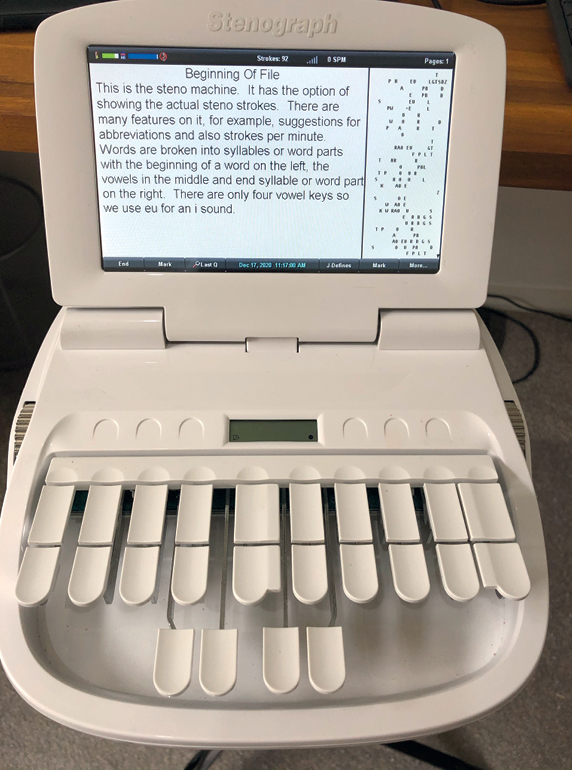

How does the stenotype machine work?

The steno machine is digital and connects to a laptop which has the software program built in. It’s like a small keyboard but it doesn’t have all the letters of the alphabet. It’s based on phonetics and you can hit the keys simultaneously. If you had the word “rough” you would hit the letters “RUF”. It then matches it up to our dictionary which converts everything into English. Sometimes it’s not going to come out phonetically, so we need to finger spell which requires typing every individual letter. There’s a system for doing that which slows you down. It’s a bit like playing the piano. There’s not every letter of the alphabet on the keyboard so we press combinations of letters to form different sounds. There’s no letter “N” so we have to press three keys to make an “N” sound.

Why did you pursue a career as a court stenographer?

I was working at Parliament House in Adelaide and saw a steno in action. Luckily, an opportunity came up for me to join the course. It took me two years before I was fully functional in the courts. I started in 1980 and it’s changed so much since then. Previously, the steno machine recorded our notes on a piece of paper and then we had to manually type it out. When computers came in, it all changed very rapidly.

What have been the most interesting cases you’ve worked on?

I’ve worked on Royal Commissions and high-profile murder trials. No day is ever the same. I did work on the pelvic mesh implant case in Sydney, which I found interesting. There was a lot of specialist evidence in that case. I also worked on a trial that has become a High Court authority, so it often comes up.

What have you learnt in the role?

I’ve learnt about a wide range of subjects from experts in forensic science, DNA, ballistics, medical practitioners and specialists, psychiatric and psychological evidence, car crash reconstructions, company structures, white collar crime and even wind farms. I’ve also learnt to develop coping strategies because sometimes the cases are quite distressing. As a stenographer you can’t show any emotion. You have to remain completely impartial because you’re there for the court.

What are the biggest challenges?

Strong accents, foreign names and if two or more people speak at once. Often witnesses are very nervous and speak really quickly and not clearly. I’ve had weeping witnesses and I haven’t liked saying “could you repeat that?”