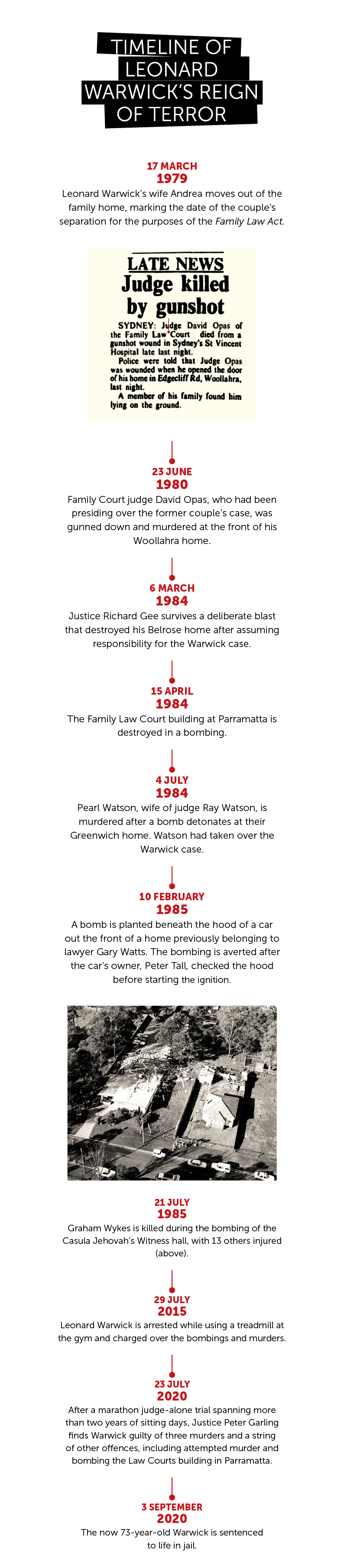

The Family Court of Australia was in its childhood years when Leonard John Warwick unleashed a five-year reign of terror. Judges and their families were targeted and murdered. Homes and the Family Court building in Parramatta were bombed. The judiciary endured decades of fear the killer could strike again or that a new and emboldened attacker would emerge. With Warwick recently sentenced to life behind bars, we explore how the case changed family law in Australia forever.

All images: NSW Police

Alastair Nicholson was the newly sworn-in Chief Justice of the Family Court of Australia in 1988 when he noticed something strange as he walked down the street near the Sydney registry.

“I suddenly noticed two men walking behind me and I asked who they were. I was told they were federal police, there for my security and protection,” he tells LSJ.

“It was a strange feeling but over time I got used to it. And while the fear of the bombings certainly subsided in the years following, the concern was always there.”

Former Chief Justice Nicholson took over the jurisdiction four years after Leonard John Warwick, a firefighter bitter at the loss of power and control following his marriage breakdown, wielded his anger on those he deemed responsible for crushing his world, forcing him to yield at the mercy of court orders.

The Family Law Act 1975 was one of the most significant reforms of the Whitlam government, shifting judgments on the “irretrievable breakdown of a marriage” from state Supreme Courts to a new separate, federal court system. The Act repealed the Matrimonial Causes Act 1961, which had been based on fault. Under this new system, couples did not need to demonstrate grounds for a divorce.

Warwick’s crimes – the murder of one judge and the wife of another, a murder attempt on a different judge at his home, and the bombing of the family law courts building in Parramatta shook the foundation of a jurisdiction barely out of infancy.

It was the first time in Australian history a sitting judge had been targeted. The feelings of terror for judges and staff of the high-stakes and heartbreak plagued jurisdiction were eased, but certainly not eliminated, as the years went on.

In light of Warwick’s conviction, it is almost too easy to forget the lingering fear of his crimes, made more palpable by the fact that for 30 years he went undetected. During the time he was at large, the judiciary also experienced serious threats and dangerous commentary regarding its function to oversee and formalise family breakdowns. This became particularly aggressive in the 1990s with a surging men’s rights movement accusing the court of bias against husbands and fathers.

“It became very fashionable to criticise the court, more so than you would expect,” Nicholson tells LSJ.

On 3 September this year, Warwick was sentenced to spend the rest of his life in jail by the NSW Supreme Court, having been found guilty in July of three murders, an attempted murder charge and the bombing of the court building in Parramatta in April 1984. At the time of the crimes, Warwick and his estranged wife had proceedings afoot in the Parramatta registry.

Justice Peter Garling wrote in sentencing the 73-year-old Warwick: “A sustained period of violence aimed at an Australian Court and its Judges solely in retribution for those Judges properly executing their obligations and functions in peacefully adjudicating disputes in accordance with the law, cannot be viewed as anything other than an attack on the very foundations of Australian democracy. It is an offending which, at its core, is completely antithetical to the very foundations of government in Australia.”

Family Court Justice David Opas, who had briefly blocked Warwick’s access to his child for breaching a family court order, was gunned down at point blank range and killed on the doorstep of his home in 1980.

The court heard that during one exchange in the family court dispute, weeks before his murder, Justice Opas admonished Warwick for not returning a cot to his ex-wife and warned him, “do not play with me. The next time you come to court you better bring your toothbrush if you are going to carry on like this”.

Warwick’s ex-wife Andrea Blanchard told police that, not long after that exchange, Warwick said to her during a lunch break near the court, “You don’t have to worry about Judge Opas, he won’t be there much longer.”

Following the murder of Justice Opas, the home of Justice Richard Gee, who looked after the Parramatta list following Justice Opas’ murder, was also bombed, but he and his family survived.

Pearl Watson, the wife of Justice Ray Watson, was murdered at their home a few years later. Warwick’s matter came before Justice Watson because Justice Gee was in hospital that day with injuries from the explosion at his house and the judge subsequently had carriage of the case.

The Crown case against Warwick also extended to other members of the community that prosecutors alleged he bore a grudge against for his marriage breakdown. He was also convicted of the murder of Graham Wykes at a Jehovah’s Witness hall after holding the congregation responsible for assisting his wife and child rebuild their lives, but acquitted of the murder of his former brother-in-law, Stephen Blanchard.

A killer unmasked

Upon his arrest in 2015, Warwick again confronted a justice system he viewed with spite, this time from behind bars. He pleaded not guilty to all charges and in May 2018 a judge-alone trial began. It would span 207 sitting days.

Justice Garling returned his verdicts with live-streamed remarks in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic on 23 July. He had also heard and ruled on 91 applications, both pre-trial and throughout the trial, of more than two disjointed years in the court. Warwick’s counsel filed a range of motions, mostly concerning subpoenas for witnesses, challenging the admissibility of evidence and attempts to adjourn the case.

Elizabeth Evatt, the first Chief Justice of the Family Court and the head of the court at the time of the bombings, said in her decision: “Nothing can repair the grave harms he has caused to so many.”

“His malevolent violence against the Family Court and those connected with it destroyed many lives and caused deep grief and irreparable harm to his victims, their families and to many of us in the Court,” she said.

“We were deeply shocked and grieved … [but] the families of David Opas, Pearl Watson and the other victims of Warwick’s violence must have some sense of relief now that he has been brought to justice. However, none of us who have been so deeply affected by his crimes can ever forget those who were his victims.”

Justice Garling noted “each of the family members of the Judges who were targeted have suffered substantial harm because of the offender’s crimes. They have suffered, not because of anything they did, but simply because they were family members of a person motivated by public duty to serve as a Judge of the Family Court of Australia.

“They were entirely innocent victims, collateral to the offender’s criminality, and they have suffered over a very long period of time because of it.”

Living in fear

The protection for judges felt scarily necessary in the era. Nicholson recalls Sydney judges in that era had security stationed overnight at their homes. It was not just that the killer remained at large, but harmful rhetoric that sparked fear in many in the judiciary that other attacks could occur.

“When I started as Chief Justice the court was still in a very shattered state. There was a lot of concern, particularly in Sydney,” Nicholson tells LSJ.

“Some were scared and there was a very good reason to be: the person responsible had not been caught. It meant the court had become a place to be fearful in.

“It had a devastating effect and also what did not help was there was a lot of attention and a lot of media, public and political commentary on the court, as though the bombings had been the court’s fault and the court had brought this on itself.”

Justice Garling singled out the judiciary staff for continuing to do their work despite crimes that “could only have engendered sheer terror in the hearts and minds of all Judges and staff of the Family Court of Australia, Judges of other superior courts and the lawyers who practised in those courts”.

“They must have felt absolute fear at the prospect that any one of them might have been the next target for simply doing what all Australians expected and wanted them to do in the course of their public duty,” Justice Garling said in his judgment.

“One of the features which has become apparent in the course of this trial, and which I now wish to publicly acknowledge, is that all of the Judges, their families, the practitioners and the staff of the Family Court of Australia, particularly those at the Parramatta Registry, exhibited extraordinary public service and bravery by continuing to undertake their roles without significant interruption so as to ensure that the Family Court of Australia could carry out its important function in the resolution of disputes involving the breakdown of marriage and the custody and welfare of children. They were courageous to do so.

“They put their public duty, the importance of the litigants and the resolution of their disputes before their own personal safety. These men and women were brave, they were courageous, and they were unbowed by the offender’s vicious and violent attacks. Australia owes them a very great debt of gratitude.”

Nicholson and his colleagues from that era have remained in touch and have followed the case closely.

“It has been an extraordinarily long process and I certainly have been taking an interest in it. I thought the trial judge did a great job,” Nicholson says.

“His comments were very good, and very accurate about the impact the case had on the Family Court.”

He says in the years following there were other threats made to judges, but they were “never regarded as much more than just a nuisance compared to what had happened in NSW”.

Nicholson says comments or criticism suggesting parties in the family court could be driven to such attacks and violence “was most unfair”.

“It completely misunderstood the approach that the court had to its clients, who were often in very difficult circumstances and you do whatever you can to help them,” he says.

Moving forward

In a statement, the current Family Court Chief Justice William Alstergren said: “These events constituted a very dark period in the history of the Court.”

“Throughout this period, the judges and staff of the Court demonstrated enormous courage by keeping the doors open and continuing to deal with the work required of them in what must have been frightening times,” Chief Justice Alstergren said.

“Hopefully [the] outcome provides some relief and resolution for the victims’ families and for the many people who were impacted, including current and former judges and staff.”

Other senior legal figures also marked the end of the case, which Nicholson describes as “a landmark”, by noting its legacy on dispensing justice in Australia.

Law Council of Australia President Pauline Wright said: “These attacks by an individual on members of the judiciary went to the heart of justice in Australia. Any attempt to intimidate a judicial officer to achieve a desired outcome or to punish them for an unfavourable outcome is deplorable and must be condemned.”

Shortly after the sentence, Nicholson spoke with another judge from that era who expressed relief at the outcome.

“The word ‘closure’ can be overused, but I think the fact this man had been caught did give her a sense of closure and relief that this was all over,” he tells LSJ.

“I feel for the victims of this very much. For the judges involved, they were all affected in different ways. For the Judge [Justice Richard Gee, who died in 2017] who had his house blown up while he and his children were there … you don’t ever fully recover from that sort of thing but he bravely continued for many years.”