“… the system is completely overloaded … there are a lot of people in jail who never get to see a psychologist or a psychiatrist and, for those that do, depending on the risk assessment, the contact is intermittent.”

A large proportion of prisoners suffer mental health challenges even before they are incarcerated, and prison conditions make things worse.

It’s glib to pretend the existence of absolutes, but there is almost nobody in the justice system who believes that incarceration is a suitable punishment for mentally ill people, or that they might emerge from prison recovered, chastened, rehabilitated or corrected.

And yet 40 per cent of prisoners in NSW jails report that they suffer from a diagnosed mental illness.

“In fact, the percentage is likely to be higher,” says Honorary Professor Richard Cogswell SC, tutor in Mental Health Law and Practice at the University of Wollongong, former District Court judge, and former President of the NSW Mental Health Review Tribunal.

“I’ve assessed roughly 30,000 people in 45 years,” says veteran prison psychologist Tim Watson-Munro. “They all have mental-health issues, in varying degrees of intensity. More often than not, they have a prior history of severe depression, anxiety and overarching substance-use issues.”

The experience of being charged with an offence is intrinsically stressful. “By the time they’re up for sentence, they’re more or less all depressed,” says Watson-Munro.

Prison itself is a depressing place. Many prisoners struggle to cope with their change in circumstance. This is largely unavoidable, though with adequate treatment and oversight adjustment disorder could be managed alongside more severe conditions.

“But the system is completely overloaded,” says Watson-Munro. “You’ve got not enough people to deliver what’s required and, consequently, there are a lot of people in jail who never get to see a psychologist or a psychiatrist and, for those that do, depending on the risk assessment, the contact is intermittent.”

Veteran prison psychologist Tim Watson-Munro

Veteran prison psychologist Tim Watson-Munro

A NSW Justice Health & Forensic Mental Health Network study found that almost 20 per cent of participating prisoners had previously attempted suicide, and their needs have to take priority over those of lower-risk patients.

But a prison is not a hospital, still less a mental hospital.

Damien Linnane, a PhD candidate and former NSW prisoner who has delivered lectures to lawyers about mental health in prisons, says he once reported to prison staff that he was depressed. “The prison doesn’t have any treatment available, but they still have a ‘duty of care’ to make sure you don’t self-harm,” he says. “The only way they can do that is by keeping you under 24-hour observation.”

Linnane was placed in solitary confinement. “The irony wasn’t wasted on me that the way the prison reacted to my depression was to deprive me of exercise, sunlight, the ability to call my family, see my friends and have social interaction,” he says.

“I was only in there for a few days and the prison GP came to see me and she said, ‘Damien, they’re not going to let you out of here until you’re no longer depressed. Do you understand what I’m trying to tell you?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ And she said, ‘Are you still depressed,’ and I’m, like, ‘No, I feel much better now’.”

Linnane says some prisoners choose not to self-report their condition because of the stigma attached to mental illness and the fact they cannot access any useful treatment anyway.

For those whose condition predates their arrest, “I think the solution is that we need more treatment facilities in the community,” says Watson-Munro, “so that we get to them before they break the law to the point where they go to jail.”

Once again, there is almost nobody who is prepared to speak against this idea – but almost no chance of its happening any time soon.

Mental health services in custody are delivered collaboratively, with Corrective Services NSW providing psychology and Justice Health NSW offering psychiatry and mental-health nursing to patients with more severe and enduring mental-health needs. There are about 255 psychologist roles in Corrective Services NSW, including 160 inside correctional centres.

“When a person enters our custody, they are screened and assessed for any risk factors for self-harm or suicide,” says a Corrective Services NSW spokeswoman. “If someone is identified as at risk, it is immediately escalated to the attention of Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network staff and the on-site Risk Intervention Team. Acute cases can be referred to the specialist Mental Health Screening Unit and Acute Crisis Management Units for more focused care.”

While a prisoner may ask to see a psychologist at any time, she says, “all referrals are triaged and allocated a priority which corresponds to the urgency and psychological need.”

What does that mean in practice?

The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), which is supposed to subsidise medicines for “all Australians”, does not operate in jails.

“Because there’s no PBS,” says Linnane, “when you go in, all your medications will be taken off you and, if you’re very lucky, you’ll see a doctor in two or three days – at which point you can try and get some back.

Former prisoner and current PhD candidate Damien Linnane

Former prisoner and current PhD candidate Damien Linnane

“Because there’s no PBS, when you go in, all your medications will be taken off you and, if you’re very lucky, you’ll see a doctor in two or three days – at which point you can try and get some back.”

“It’s normal to have to wait a couple of weeks, “ Linnane adds. “If you’re unlucky, you might wait six weeks. So, people go in on really high doses of anti-depressants or anti-psychotics, and they just go cold turkey – and a disproportionate amount of suicide attempts and violence happen during this time.

“And when they finally get to see a doctor, they don’t necessarily get their medication back – because in prisons [instead of] PBS, they have an approved list of medications.

“So, you might’ve spent decades finding the right medication for your mental-health condition and you go to prison and the doctor might say, ‘No, we don’t have that anti-psychotic, so we’re going to put you on this one instead’.”

A spokesperson for the Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network comments that Justice Health NSW staff endeavour to confirm any current treatment with the patient’s community treatment provider.

“If this cannot be confirmed,” says the spokesperson, “the patient will be further assessed by a Medical Officer or other appropriately qualified practitioner prior to recommencing treatment. As per Corrective Services NSW policy, patients are not permitted to keep medications with them and they are provided to Justice Health NSW for storage. In most circumstances patients will remain on the same medication in custody as they received in the community, to prevent treatment interruptions. This is dependent on individual circumstances and safety considerations attached to certain medications.”

Cogswell says, “District Court judges sentencing prisoners are often presented with psychiatric and psychological reports about the offender. They may be from a treating clinician, or one retained for an opinion. My practice (shared by other judges) was to ask the legal representative whether their client would agree to me sending those reports into custody with their client. Corrective Services’ health providers said they can be very helpful in assessing the prisoner’s initial and ongoing mental (and other) health needs. Not all prisoners wanted their reports sent to prison with them: hence the importance of obtaining instructions.”

Cogswell advises defence lawyers: “If your client is on medication and you are obtaining a report about their mental health, it might be worth asking the clinician to comment on the importance of your client remaining on that particular medication and any warning they may have about abrupt cessation of that medication.”

Honorary Professor Richard Cogswell SC, educator, former judge and President of the NSW Mental Health Review Tribunal

Honorary Professor Richard Cogswell SC, educator, former judge and President of the NSW Mental Health Review Tribunal

“If your client is on medication … it might be worth asking the clinician to comment on the importance of your client remaining on that particular medication and any warning they may have about abrupt cessation of that medication.”

Watson-Munro says he always alerts the system of the dangers ahead. “I inevitably put it in reports: I say it’s unlikely that this person will get the sort of treatment he requires in a custodial environment and this is why they need to be closely watched. You try to fast-track the process, but the problem is that they all need fast-tracking.”

He points out that mentally ill prisoners face difficulties even before they are sentenced. “You’re not going to see a psychiatrist until you’re sentenced and classified,” he says. “People on remand, as a matter of protocol, don’t have access to mental-health practitioners or treatment programs.” They may struggle to get medication and can be moved from one jail to another without notice. “So that adds to the dislocation and instability that they experience anyway by being in jail,” he says.

In 1985, Watson-Munro and Dr David Sime completed a study on suicide in prisons in Victoria, which found that the most vulnerable period for somebody going into jail was the first two weeks, and then 10 years into a sentence: “They’ve got a long sentence, they’ve done 10 years, they’ve got another 10 to go, so the despair creeps in because they’re only halfway.

“So we said you need to have better reception, better classification on reception, you need to have mental-health practitioners assessing them when they come into jail, and you need to have peer-group monitoring: you don’t have them one-out in a cell, you have them two-out, so people can keep an eye on them.”

Incarceration aggravates depression among a population that is already severely depressed.

Incarceration aggravates depression among a population that is already severely depressed.

“That’s why they get into the gear,” says Watson-Munro. “The drug exacerbates the depression and balms the anxiety. Then, going to jail, their mood deteriorates, for all the obvious reasons: they’re deprived of their liberty; they’re worried about their families; if they’ve got a long lagging, it’s very problematic for them.”

How many of his clients have substance-abuse issues?

“It’s more how many don’t,” says Watson-Munro. “In a typical week, I reckon, conservatively, 95 per cent of the people I assess have a substance use problem. And the drug of choice is ice. Ice is like a wrecking machine. It cuts swathes through people’s personalities, their judgement; they have poor impulse control; they need more and more of it; the comedown’s terrible …”

Ice drives mental illness. “There’s a lot of research on this,” says Watson-Munro. “Just about every bloke and woman I assess with an ice addiction will say they hallucinate in the same way that schizophrenics do: they hear things, they see things. They become very paranoid, which makes them dangerous. They get rebound depression, which makes them dangerous. What galvanises all this is ice has a dramatic impact on the pre-frontal cortex of the brain, which is the brain structure that is responsible for judgement, cognition, consequential thinking and integration of personality. So, inevitably, if you use ice you’re going to unravel.”

That said, one of the few positive things that can come out of incarceration is an enforced spell of detoxification. Some prisoners deliberately take the opportunity to come off ice – if only because the drug is expensive on the jail black market and falling in debt to drug dealers can only lead to even worse problems when you are locked up 24 hours a day with your lender.

Another ray of light, for high-risk offenders at least, seems to be the Violent Offenders Therapeutic Program (VOTP), a high-intensity program that runs for approximately 10 months, during which time offenders spend up to 300 hours with psychologists.

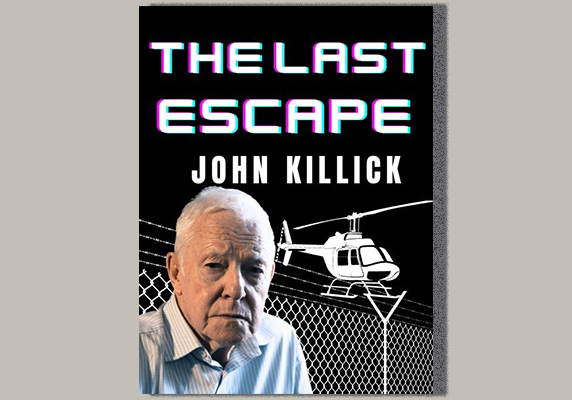

Former armed robber and serial escapee John Killick, who spent 40 years of his life in (and out) of jails in NSW, Victoria and South Australia, began the VOTP in Silverwater Correctional Complex and was eventually allowed to leave jail once a month to attend meetings in Sydney. (This was a step that the jail was reluctant to make, since Killick rose to international fame when his Russian girlfriend hijacked a helicopter and broke him out of Silverwater in 1999.)

Killick describes the VOTP as “the jewel in the crown” of Corrections NSW.

“It gets people out of jail and into town, where they’re treated like human beings by the psychs,” he says. “The psychs take a genuine interest in them and when one goes back into jail, the psychs feel it’s a personal failure. I know they put their hearts into it.”

At first, Killick was uncertain whether he would fit into the program. “I didn’t see myself as a violent offender,” he says. “I was a person who bluffed his way in banks, but armed robberies are considered that sort of offence so they accepted me.”

In the first stages of the program, participants were locked in the wing of the jail where the sessions were held. Other prisoners often assumed they were paedophiles on protection.

“We did a lot of group work,” says Killick, “and we also did one-on-one with psychs.”

Killick never shot anybody during an armed robbery and therefore believed that he had not committed a violent act. “They got through to me how many people I might have harmed by just bluffing,” he says.

He imagined his life partner, Gloria, going to make a withdrawal in a bank in her seventies. “At her age, and if someone ran in brandishing a shotgun, with a balaclava on, screaming at everyone, she could have a heart attack. I never intended to shoot anybody, but I realised it’s a violent crime.”

At a VOTP session, two psychologists run the discussion in a room full of violent offenders and begin by asking how their lives have been going recently.

“They find out what the problem is,” says Killick. “My problem was gambling. They assessed me as a risk-taker, and that’s exactly what I was. So I worked on that. Others had short fuses. A lot of them had to work on impulse control.

“I’m a chess player,” Killick adds, in a voice that suggests a degree of despair about his younger self. “Let’s face it: if I’d really thought it out, I wouldn’t have got into a helicopter. What’re the odds of getting away with it? We nearly got killed.”

He feels the VOTP offered him insights.

“The psychs are smart,” he says. “They ask the hard questions.

“When I first got there, I had a psych yelling at me: ‘You robbed banks! You shouted at people! How does it feel to get shouted at back?’

“She was pretty good.”

Anyone in the room can ask questions of the person in the hot seat, and it’s oxymoronic that violent offenders can be brutal.

“You work hard for six months, then you go in and do therapy,” says Killick. “You listen to other guys, and you hear what they’re doing and you realise, ‘That’s what I used to do.’”

He adds, “Half the guys aren’t serious. They’re just going through a process. But people do come good.”

The Corrections NSW spokeswoman says, “In the 2020/21 and 2021/22 financial years there was a 100 per cent completion rate for this program. In the 2022/23 financial year, there was a 91 per cent completion rate. The average completion rates for similar programs sit at about 70–75 per cent.”

“When I came out,” says Killick. “I kept going when I didn’t have to go. Even when my parole finished, I kept in touch.”

Again, it would be difficult to identify anyone with knowledge of the corrections system who would argue against putting in place more programs to enable less dangerous prisoners to break the cycle of their destructive behaviour.

But perhaps it would be even harder to find politicians who are prepared to argue the case for more public money for mental-health services in jail when there is not enough money for mental-health services outside of jail – which, of course, is a good part of the reason that some mentally ill people end up incarcerated in the first place.

Lifeline: 13 11 14

Solicitor Outreach Service: 1800 592 296