Unlike legal contracts for office workers, where the hours of work, environment, tasks and deliverables are clear-cut, dancers likely have a single tool – their body.

Dancers are likely to move from company to company, from location to location. An appreciation of what their lifestyle entails is elemental for lawyers to working effectively within the industry.

According to Ausdance National, the peak body advocating for and servicing the dance sector in Australia, data collated in 2013 indicated that there were over 50 dance companies and in excess of 200 choreographers in Australia. Some of the companies are funded by the Australia Council for the Arts (including the Australian Ballet, Bangarra Dance Theatre and Sydney Dance Company), while others rely upon local, state and territory governments, or are self-funded.

Dance is an industry that is “undervalued”, Lizzie Vilmanis, the President of Ausdance, says. The role of legal professionals in working with the dance industry is a complex one, she believes, since there is such diversity in the industry.

As much as COVID-19 impacted the industry, Vilmanis says many of the dilemmas faced by that industry: recognising and providing avenues for First Nations people to be paid for their leadership roles; addressing the power imbalance between independent artists and major organisations in establishing fair deals; and genuine inclusivity of all nations, body sizes and shapes and socioeconomic backgrounds, were only exacerbated by the pandemic.

She tells LSJ how lawyers can work effectively with professionals within the dance performance sector of the dance industry, and what to take into consideration in communications with all parties from executives through to independent dancers and choreographers.

“Everything that dance is about is being human and developing the cultures that we live in, share and build together. For lawyers to do their research into that, to go ‘what is the value of dance?’, enables them to represent dance or deal in dance. When you answer that question, you’ve got the knowledge to be an advocate,” she says.

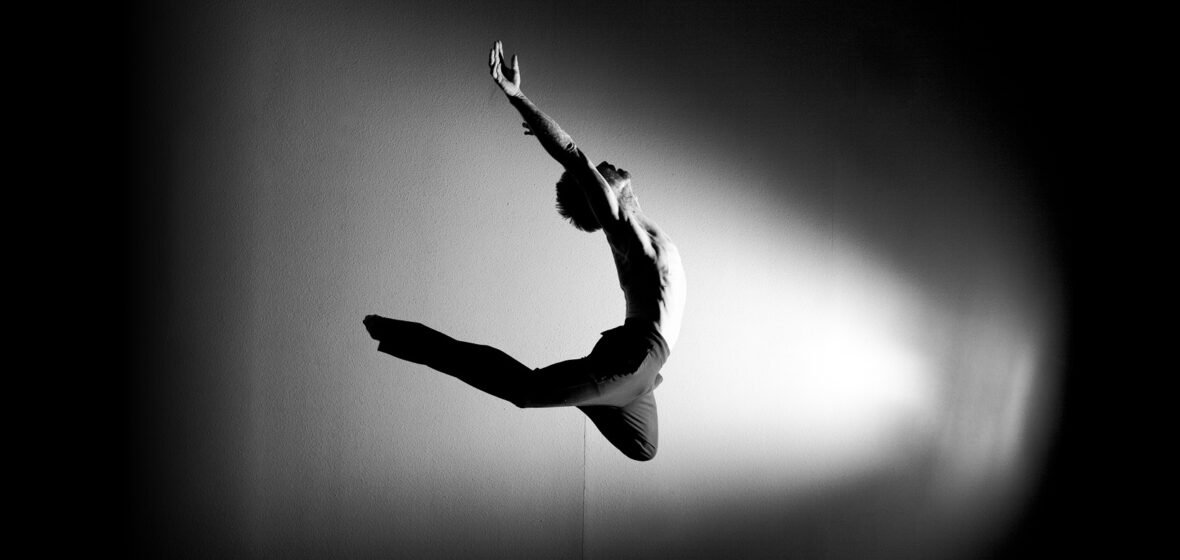

Artists, bodies, professional commodities

Dance is a profession that relies strongly on independent artists, technical and creative professionals. It is also a demanding profession, not least from a physical standpoint. A safety report into the dance industry in 2017 indicated that, of the 195 professional dancers aged over 18 who were surveyed, 97 per cent reported at least one significant injury in their career and 73 per cent had experienced a dance-related injury in the previous 12 months. A concerning 62 per cent of professional dancers believed that there was a stigma in acknowledging their injuries, and only half agreed that they would reveal their injury to an employer.

“The first thing is to be aware that you’re talking about a body, and not something that sits aside from who a dancer is as a person,” Vilmanis says.

”It’s hard to separate yourself from your body as a tool. When it comes to discussing contracts, artistry comes from the person, so it’s important to recognise that your commodity is a human being. Issues arise pertaining to body shape, body colour, cultural background, and mobility – you have to show compassion and understanding regarding most aspects of human rights.”

Working with dance executives

There is complexity in juggling business interests with the creative essence of dance.

“Dance is not always treated as a business,” Vilmanis explains. “A lot of focus is put on the performance element, forgetting that, to support that, you have to run a business. Having the legal knowledge and language to be able to conduct and speak about business is often something that’s lacking for professionals who are trained to dance.

“The change we want to make in the industry is limited by traditional systems and structures that have not been set up to enable more a more diverse, inclusive sector. There’s discussion with lawyers about how we can best make that happen as it involves making changes to our constitution and other policies and procedures.”

Legal contracts for dance professionals?

“In contracts for dancers these days there’s growing focus around matters to do with consent,” Vilmanis says. “There’s a new position being talked about in the industry – that of an intimacy coach – that is looking into the consent that happens within the rehearsal room and performances.

For dancers, issues about working include matters to do with the body: what you are and are not allowed to do in terms of safe dance practice, how long and intensively you can work people for. And directors have quite a collaborative process with artists, so it’s important contracts make it clear who owns the work if a partnership has been involved.

Vilmanis concedes there is a power imbalance the industry needs to address: major organisations are favoured over independent artists when it comes to their intellectual property and negotiating favourable contracts.

She cites the example of a dancer who was contracted to an interstate company, but whose contract did not allow for any financial support in moving to a new state and leaving their established life behind.

There are many other roles in the industry also affected in this way. Choreographers, for example, work as freelancers for hire in most cases.

“Independent choreographers are contracted in to create short works for a season, or one long work, but often they’re not from the company. Often, there’s a certain time frame in which the work is owned by the company. And in that regard, those institutions and companies have access to legal resources that independent artists do not. Independents often don’t have the resources to access legal assistance to understand the contract and what they’re agreeing to.

“It’s very hard to ascertain who owns what in dance. Not everything is written down on paper, so you can identify that you’ve seen that before. Does a bit of choreography belong to someone else, and how do you prove that? We have a common language through the body, but then, what becomes unique to a particular person?”

Legal education and partnerships need to be more comprehensive

To address the power imbalance and increase fairness, instilling a basic understanding of contracts and what independent dance professionals are agreeing to is necessary. This may require a better collaboration between the law profession and the dance institutions.

Vilmanis says, “We very much need legal advice and education from university level so that independents and dancers are schooled in how to read contracts, what kind of insurance they need, who is responsible for that insurance, workplace health and safety, pay rates, clarity around what roles within the industry entail, and intellectual property. Is someone employed to direct, to choreograph, to design their own costumes? There are all these different layers involved in the process and so much of it is not visible.”

Because the industry is so competitive, independent artists who rely upon their reputation and contract work may be fearful about raising concerns or appearing argumentative. Finding a better balance between fairness, business and cultivation of creativity is a difficult task.

An industry requiring sensitivity and inclusivity

Vilmanis believes it is essential for First Nations lawyers to be involved in discussing legal matters and contracts with dance organisations, owing to their cultural knowledge and cultural sensitivities, and the nuances of language and bodies. She would also like to see more legal engagement and education within dance education, and a greater representation of different culture, nationalities, languages and the diversity of Australian society in the dance industry. Equitably, of course.

Whilst it may be difficult to imagine the overlap between the legal profession and professional dance, there is a rhythm between the two worlds. Jess Oehm is a final year law student at Western Sydney University. She has been a dancer since an early age, devoting hours to training, rehearsing and performing, and roles included performances as a young dancer with Bangarra Dance Theatre.

Having to support herself throughout her law studies has been very demanding, but, as Jess says, “My years as a ballet dancer gave me a sense of pride in being presentable, and taught me strict time management and organisational skills.”