Silverwater Correctional Complex in western Sydney is one of NSW’s most notorious prisons, having housed convicts from Rene Rivkin to Kathleen Folbigg since its opening in 1970. It is also one of the busiest in the state – as it not only accepts prisoners convicted under state and Commonwealth law, but also serves as a reception for inmates on remand. Corrective Services Commissioner Peter Severin took us on an exclusive tour inside the prison, discussing the challenges and changes he has faced during a 40-year career on the inside.

Photography: Jason McCormack

Ask Peter Severin to nominate the single-most profound change to hit the prison system in the 40-odd years he’s been in corrections and you’ll likely get a single-word answer: drugs.

When the NSW Corrective Services Commissioner walked into his first jail in north-west Germany in 1980, the most the 24-year-old rookie was likely to find when he tossed a cell was a little bit of cannabis or LSD, perhaps some heroin. The harder stuff – cocaine, opioids, the drugs that send inmates psychotic or kills them in their sleep – was virtually unheard of.

That has changed to the extent that managing drug-affected prisoners is now one of the main challenges for prison officers.

“[A] large number of people come with acute symptoms of withdrawal, or at least it is evident that they have misused drugs,” Severin tells LSJ. “That’s what the staff have to deal with. That’s the reality. And that is quite different to when I started with my job.’’

It has been 40 years since Severin began a career in corrections. The 64-year-old German migrant (Severin’s mother was Australian, his father a German doctor) arrived in Australia a naive 32 year old, armed with a sociology degree and a few years’ experience as a casual prison officer in Germany.

Oddly, it was the degree rather than the job that landed him a role at Brisbane Correctional Centre, then the Sir David Longland Correctional Centre. Severin spent four years working as a social worker at the centre before moving back into the operational end of the prison system. It would not be a stretch to say it was his background in sociology that has guided his approach to corrections.

Prisons will never be places of Aristotelian contemplation and reflection, no matter how creative those who run them are. But, more than most, Severin has tried to emphasise the opportunities for reform of the prison system. Now he is the NSW Corrections Commissioner, a job he inherited from Ron Woodham, an old-school prison boss who ran the NSW system from 2002 to 2012.

The two men couldn’t be more different. Severin is softly spoken and urbane, more schoolteacher than security guard. He began his career on a graduate trajectory, although he has been in his fair share of scraps. No officer who spends more than a few months inside a prison escapes the dangerous reality of prison life. Severin has been king-hit and quelled riots. But these are not the experiences he emphasises when he reflects on his four decades inside the prison system.

“The experiences of having a constructive engagement outweigh the things that you actually unfortunately are subjected to as a prison officer,’’ he says. “For me, it was always really about the experience I had in working with people, staff and prisoners alike.”

Managing prisons is, for most, an unenviable job. The system’s two main purposes – rehabilitation and punishment – are in theory complementary, but in practice often at odds. The politics are tricky. Enlightenment notions of progress and perfectibility fall on sallow ground in an environment that rewards toughness and punishes subtlety.

Few politicians have campaigned and won parliamentary seats on a platform to soften prison conditions and temper the laws that helped create them. The impetus is all in the other direction: “tough on crime” is a more popular stance. Thus, decades of law and order one-upmanship have seen the NSW prison population balloon from around 7,300 in 2000 to 12,800 today.

Today, however, the main challenges the system faces are drugs and mental illness.

Prison officers to whom LSJ spoke on condition of anonymity estimate that at least 60 per cent of prisoners coming in off the streets are in some way affected by drugs. (Severin doesn’t disagree.) The biggest problem is ice, which is readily available and easily smuggled into prisons. It contributes to hyper-volatility among inmates, but also an explosion of mental illness that staff are struggling to manage.

Attempts to keep drugs out of jails have proved as futile as attempts to ban weapons or phones. Prisoners always find a way. Still, authorities must try. Severin’s latest initiative is by banning original hard copy letters.

“Nobody gets an original letter anymore,’’ he says. “They get photocopies of the mail that comes in and the rest is shredded. I can’t have my staff having to finger through mail and identify whether its laced with anything or not.”

Silverwater complex at a glance

Opened in: 1970

Capacity: 1,200 inmates

Facilities:

- One maximum security facility for women.

- One maximum security facility for men.

- One minimum security centre for men.

Construction is currently underway to expand and upgrade the complex.

This includes:

- New 110-bed accommodation blocks.

- New “safe cells” for at-risk inmates.

- Upgrading and supporting infrastructure to meet the needs of a large workforce and inmate population.

Construction is expected to finish in 2021.

At the Metropolitan Remand and Reception Centre, one prisoner we find doing leg-presses using industrial detergent bottles as weights puts the dilemma of prison life more bluntly: “This is the beginning, so nobody’s happy.”

The prisoner is referring specifically to life in a remand centre. The MRRC, better known as Silverwater Jail, is the first footfall for prisoners coming in off the street or transiting through other jails. It’s a shifting, volatile environment where the inmates are unsentenced and the average stay is no more than a few months. Fates are uncertain, hierarchies are fluid. Drugs are everywhere. For prison staff, the challenge is not just in managing a high number of drug-affected prisoners, it is dealing with prisoners about whom they know very little.

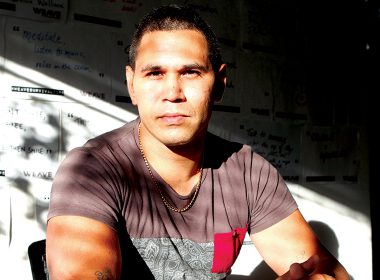

Our guide through the MRCC is a cheerful Islander named Sam Mariner. Mariner has worked at Silverwater on and off for the best of 20 years. He is a friendly, genial sort of chap who one suspects could diffuse most confrontations with a chat and a smile, although his hulking shoulders make it clear he has other means at his disposal, should the situation require them.

“Methamphetamines has changed it,’’ Mariner says of Silverwater. “And gangs.’’

Mariner escorts us through Silverwater’s main reception area, a large cavernous area that once housed lounges and televisions. Outside, truck bays back into holding cells. Silverwater is a hub for the state’s 38 jails. It moves more than 300 inmates a day and all must transit through reception. The reception area is a good example of what can happen when well-intentioned idealism collides with reality. Mariner says the original intention was to have an airport-style departure lounge, where prisoners could repose on couches and watch movies. The reality was chaos: fights, violence and riots.

“It didn’t work out that way,” Mariner observes dryly.

In the Darcy Unit, we encounter the other harsh reality of prison life – mental illness. Rows of safe cells house high-risk prisoners. These are the men at high risk of suicide or self-harm. They live in isolated cells with 24-hour CCTV monitoring.

In one cell, an old man with long grey hair sits barefoot on his bed, his head in his hands. In the one next to him, an inmate lies on a partially severed foam mattress, his food scattered around him like a nest. They are wretched souls, dangerous perhaps, but also ill. Mariner says the prison struggles to cope with the high number of mentally ill inmates. The deinstitutionalisation of mental health, a process that has occurred across the Western world, has had a massive impact on prisons. Men and women who in previous decades would have been kept in a psychiatric institution find themselves on the street or in jail.

“We are in many ways, for a large number of people, almost a substitute emotional and mental health institution,” Severin says. “Which, of course, our staff are not trained to manage, [but] nevertheless do that very well.”

Silverwater is being expanded. Currently, the jail has a maximum capacity of just under 1,200, although the COVID-19 pandemic has forced the numbers down to around half that.

New wings will house an additional 440 new beds. The upgrade is scheduled to be finished next year and the hope is it will relieve some of the pressure on the jail.

For lawyers, that pressure is most keenly felt in the plodding, opaque nature of prison bureaucracy. Gaining access to clients is time consuming, difficult, and frequently unsuccessful. Processes vary from prison to prison. Visits are short and often cancelled at the last moment, sometimes on the slimmest of pretexts.

Carol Younes is a partner at Younes + Espiner, a major criminal law practice specialising in serious matters. She says securing productive face time with clients inside prisons is an administrative nightmare.

“One of the main problems is restricted access and the effort you have to go through to see a client,” she says. “Then there are limitations around what you can take in with you, in terms of devices, and there are inconsistencies around getting approval to do that.”

It is a growing problem as criminal briefs become more complex and more reliant on electronic material. A major drug matter might turn on hundreds of hours of intercepted phone calls or CCTV footage, much of which will require nuanced explanations from clients.

Younes recalls one case, a serious sexual assault allegation in which the accused was eventually acquitted, which involved more than 16 hours of CCTV footage.

“We needed to go through it, and it was almost impossible to get substantial blocks of time with him. Because by the time you go out and they process you, you only get a short window. On one occasion we only got 15 minutes.”

Another problem is prisoners who claim to have been mistreated, Younes says. Many are reluctant to make complaints lest they find themselves mysteriously moved or have privileges like exercise rights or visits suddenly withdrawn. These sorts of punishments, which to the outside observer appear modest but which can take on huge significance in the microcosm of prison life, give prison officers considerable power over inmates.

To Severin, this is a fair cop. He acknowledges shortcomings around access and visitation, but argues the situation is improving. He says the COVID-19 pandemic has compressed years of technological reform into a tighter timeframe.

He says Corrections is rolling out in-cell technology that will in time allow prisoners access to their criminal briefs in their cells via customised tablets. It will also allow them to communicate with counsel via approved numbers of emails at any time.

“I accept that criticism that in some cases it has taken far too long and also that the level of engagement is not long enough because there’s a scheduling system,” Severin says. “But from where I’m sitting, it’s now important that we’re doing something about it and what we’re doing is really rolling out technology much, much faster.”

The other change roiling the system is terrorism and the challenge of containing large numbers of radicalised prisoners. Two decades of radical Islam has deposited around 40 inmates into the system. These are men and women either charged or convicted of serious terrorism matters.

In NSW, authorities have opted to concentrate such prisoners together, a strategy aimed at stemming the flow of radical Islam into the general population but which makes rehabilitation virtually impossible. Although these prisoners are not violent, Severin says they are among the hardest to manage.

“Terrorists are a group of people who simply do not want to cooperate with the system, and they make decisions based on entirely their own motivation,” he says.