Legal Aid NSW’s Refugee Service has launched a children’s book designed to make refugees aware of its services.

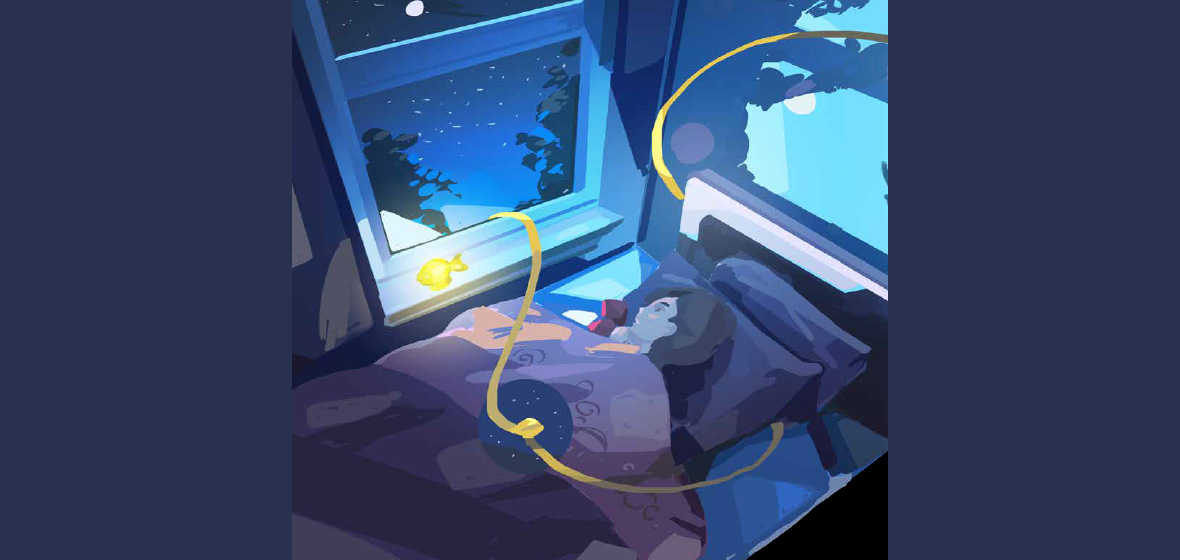

The Ribbon, by Assyrian-Australian writer Monikka Eliah, with illustrations by refugee and illustrator Hussein Nabeel, is written in the voice of a child refugee and was released during Refugee Week (19–25 June).

The book’s central metaphor, says the Refugee Service’s Senior Solicitor, Lyn Payne, “is the ribbon, which is akin to worry or anxiety or stress.”

The worries facing refugee children and their families, as depicted in the book, include parents arguing and financial stresses, as well as sorrow about family left behind in the country the family fled from: “I feel the ribbons tighten when the people we love are kept far away”.

The book offers hope, however, highlighting the support Legal Aid’s Refugee Service can offer: “We are not alone. For the heavy knots we feel, there are special hands that can try to untie them”.

The book will be included in the welcome packs given to people who are picked up from the airport by Settlement Services International when they first arrive in Australia. It can also be accessed direct from the Refugee Service at Legal Aid.

The book’s evolution began in 2020. This lengthy process was partly because of the pandemic, but also because of the need to get it right, says Nohara Odicho, Community Engagement Officer of the Refugee Service.

Odicho, who commissioned the book, tells LSJ it was important to test the tone and translations first: the English version was translated into Arabic, Dari, Swahili and Burmese, as these are the main languages spoken by the cohort of clients with refugee visas.

Odicho sourced the book’s creators through Lost In Books, a multilingual bookshop in Fairfield. “They knew the Refugee Services client cohort and could identify an author for the project, also a refugee, who arrived in Australia when she was young.”

The book is written for mothers to read with their children, aged 0-5 years, but the intended audience is the mothers themselves.

The knot in your stomach

Odicho understands very well the issues the book highlights. She and her father came from Syria as refugees in 2015.

“I know the journey of the clients,” she says, “waiting, the family being apart. All the struggles in your new life in your new country. So, I’m familiar with the challenges.

“In the book, I wanted to reflect for a child the journey of arriving in Australia: at the beginning the voices are all new, everything is big and different, and you feel that knot in your tummy, uncomfortable. I was not even a child when I came, I was 23, and I still had that knot in my stomach.”

Given her background, Odicho is highly suited to her role of connecting the community with the Refugee Service and making them aware of their rights and the services available for them. The service is based in Fairfield (the local government area with the highest numbers of refugees in NSW) but every six weeks Odicho’s team travels around NSW to reach out to refugees who have settled in regional areas.

For Odicho, this team and its work is the ideal place for her. “I always had a passion to work in community,” she says. “In Syria, my favourite author was a social worker. And then when I came here, I thought this is my chance, I can work in the field I always wanted to be in: the community sector.”

She completed her studies at TAFE and started working with refugees in a volunteer role.

Odicho possesses an acute awareness that vulnerable people need to know they can trust the service they are accessing.

One lawyer only

“I tell people that when they come to see a lawyer, they will see one lawyer only. They won’t have to repeat their story with someone else,” she says.“They are avoiding the trauma of repeating their story and building trust.”

“Our clients have a negative relationship with government agencies and law and police in their old country,” she adds, “so building that trust with them takes a long time.”

Her role is also to encourage people to trust the legal system in their new country.

“I chat to them about their rights and responsibilities. I explain the family law system here is fair for everyone and may be different from their home country,” she says. “The main thing I tell them is, if you have legal issues just come to us if you’re not sure. We can help you.”

The Refugee Service can help with almost all legal issues its refugee clients may encounter, Payne says.

“Ours is a generalist service. We all do everything,” she explains.

“None of us specialise in particular areas. With the same client we may work with sponsoring a family member overseas, and then applying for citizenship issues, and then they decide they want to get divorced; we will run all of those. The team also deals with guardianship matters, visa cancellations, insurance issues, fines, driving offences, family law issues, and contested parenting matters.”

The generalist nature of the work fuels Payne’s passion.

The poster child of a holistic service

“I think this is a brilliant service for me, personally speaking, because it isn’t just about refugee law, and about getting people a visa,” she says.

“It also covers the breadth of all of the legal issues that a person might present with. It really is a great area to work in because you get to do pretty much anything. Anything your client presents with you can help them with.

“Because refugees are recognised as a priority client group within Legal Aid we are able to do work for refugee clients in areas of law others might not be able to cover, in recognition of the particular vulnerabilities of these clients.

“We are the poster child of being able to provide a holistic service.”

Payne is as passionate about her team as she is about the work. “We’re an incredibly close team … all the others apart from me come from a refugee background,” she says.

“We’re really fortunate to have the team with the particular skill set and expertise that our clients require, but more than that they bring love and kindness and compassion, which is critical for practice here. As well as being trauma informed and culturally appropriate, we bond with our clients, and they bond with us.”

Payne adds a note of caution: “Whilst we are very committed to our clients we also know when to draw the professional line and say ‘no, we can’t help you with that’.”

‘We’re really fortunate to have the team with the particular skill set and expertise that our clients require, but more than that they bring love and kindness and compassion, which is critical for practice here. ‘

The only area of the law the Refugee Service doesn’t cover is criminal law.

“We give procedural advice but don’t represent clients in criminal matters,” she says. However, the Refugee Service lawyers can make ‘soft’ referrals to colleagues in the Legal Aid and other offices for criminal matters.

Back to the future

“I’ve been a lawyer for a very long time. I started my life as a lawyer with RACS about 30 years ago,” Payne says.

When she was studying law, Payne says, “I thought, refugee law, this is the thing that really does it for me, and then like many people I started volunteering at a community legal centre, which was RACS. And then I was very lucky to get a job there.”

“I’ve been doing immigration law for most of my career,” she adds. “Then, when I joined Legal Aid, I went into different areas and practised in discrimination law and then civil liberties work, and then in 2019 I started with the Refugee Service, so it’s back to the future.”

The Refugee Service began operating in early 2017, responding to the influx of primarily Syrian and Iraqi refugees to NSW in the previous two years.

“Fortunately for us, there was a component of funding for legal services. So that was the beginning of our service,” Payne says.

“Then the funding ended – it was a four-year cycle. But in recognising that we’ve had enormous success in the service, Legal Aid decided to continue to fund us, and so we became a permanent service, funded as part of Legal Aid.”

The numbers tell the story of success: Between January 2017 and 30 May 2023, Legal Aid NSW’s Refugee Service has provided 10,842 services to refugees, including 4,500 over the past two and a half years.

With only four lawyers in the service, Payne says, “we are very busy – and we work very long hours.”

She attributes the success of the service in part to the fact it addresses the real issues refugees are experiencing.

“I think that the dogma of successful integration and settlement, particularly for refugees, is that all that people need is proficiency in English, financial support – whether through employment or access to social security – and a place to live, and then they’re done,” Payne says. She adds, “Refugees have particular challenges, based on the fact that they didn’t choose to leave their home, they’ve been forced to – and the way you service them is vastly different to the way that you’d service any other cohort, including all the other vulnerable cohorts that we service.

“The service delivers resources to clients in ways that connect with them. The book, I think, is a great example of that.”

Recognising vulnerabilities

The Ribbon is one way “of connecting with our clients using resources that recognise their particular vulnerabilities,” Payne says. “And for us it’s not just about creating resources in written language.

“The traditional way is to create pamphlets and assume that would be accessible to people. But it’s much more nuanced than that, and you need the insights of a person like Nohara.”

Odicho agrees traditional resources are not always helpful.

“For some communities,” she says, “their language is not a written language, so we can’t just supply a written fact sheet and give it to them.

“We need to find alternatives – recorded, or short videos and especially for the older women. Often the women have not had any education, so they are illiterate in their own language.”

In some cases, Odicho adds, the husband is literate and will be able to talk about information presented, while the women “are just quiet, and if we see that dynamic, we try to find something more suitable for everyone.”

“That’s how we came up with the idea for this book,” she says.

“During community events we saw mothers pushing prams with hands full with the kids. They would come to the Legal Aid stall and take flyers on DV and family issues and stand there reading them or looking at them, and then putting them back.”

Payne says, “I think the book is a terrific example of service delivery in a way that reaches clients. It answers the questions, ‘How do I get to Legal Aid? How do I speak to a lawyer in my language, without somebody listening in?’

“It’s a safe resource, nothing overt, not just a DV resource, it’s a resource that reaches communities within our community who have not traditionally engaged with our service, for a multitude of reasons.”

“Some of the time,” Payne adds, “people present with an issue and it’s clear this is a pretext for presenting with other issues, and of course, being a generalist service, we can help with that. We can reach clients where they’re at without drawing attention to potentially sensitive legal issues.”

‘Some of the time people present with an issue and it’s clear this is a pretext for presenting with other issues, and, being a generalist service, we can help with that.’

“The demand is increasing, the clients are becoming far more complex,” Payne continues, “and that’s because we are giving advice not just about the simpler legal issues, like bringing the rest of their family here. And once a client sees you about a legal issue, they will continue seeing you for a long time.”

People who arrive with a PR visa are assisted by the Refugee Service for their first six years after their arrival. “During COVID, we extended this to eight years. Even after they become citizens, which you can do after four years, they may still have particular vulnerabilities, so we continue to assist them,” Payne says.

“We say person first, lawyer second. We really try to live like that.”