If someone is generating lots of income and there is an undue focus on money, that can produce certain behaviour at the expense of value and purpose.

Toxic cultures are still far too common in law firms, but experts advise that prevention is better than cure when it comes to tackling poor behaviour – even in a lockdown.

When she began her career as a young lawyer three decades ago, Katrina Rathie often encountered overt sexism.

“When I started out, barristers thought it was part of their obligation to hit on lawyers and ask you out. That was the culture in the workplace in the ‘80s,” says Rathie, who is now Partner in Charge of the Sydney office of King & Wood Mallesons.

While she’s pleased to note the really obvious behaviour has mostly disappeared, the statistics show plenty of sexism and bullying are still rife in legal workplaces.

“It’s staggering to see the statistics that still exist in the legal profession,” Rathie says.

“I thought it was something from years gone by. It’s surprising it’s taken so long to change, and I feel there’s been a resurgence in the statistics.”

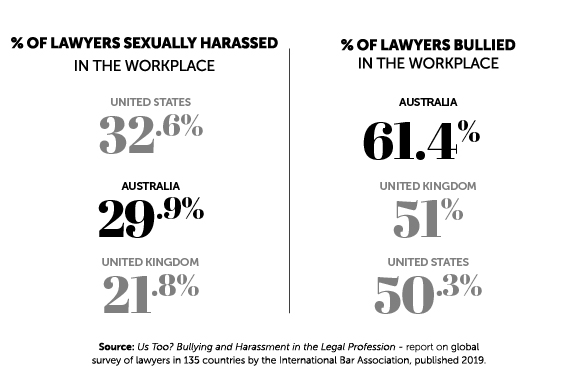

In mid-2019, a global study of lawyers in 135 countries by the International Bar Association called Us Too? Bullying and Harassment in the Legal Profession revealed that these problems remain widespread in the legal profession.

Almost 30 per cent of Australian lawyers who responded to the IBA survey reported experiencing sexual harassment in the workplace, compared with 21.8 per cent in the United Kingdom and 32.6 per cent in the US.

The numbers for bullying were even worse. More than 60 per cent of Australian respondents reported that they had been bullied at work, compared with 51 per cent in the UK, 50.3 per cent in the US, and 43 per cent globally.

Along with this global data, a handful of well-publicised scandals in professional services and law firms emerged in the wake of the #MeToo movement.

Traditional firm structures need to shift

The recently released “Respect@Work: Sexual harassment national inquiry report 2020” by the Australian Human Rights Commission also paints a grim picture of behaviour across Australian organisations. It notes that those working in sectors such as law have a higher risk of experiencing sexual harassment because the workplaces are “organised according to a hierarchical structure”.

But that traditional pecking order is changing, says Rathie.

“I don’t think we have the master-servant model that might have existed in years gone by, but it’s a power imbalance, particularly if you are a junior lawyer,” she says.

“Bullying has been around the hours that people are asked to work or deadlines. There are [now] a lot of programs put in place to make sure we have appropriate conversations with employees.”

Tackling poor norms and behaviour is often about more than rules, however, and even in a pandemic lockdown bullying can still exist.

“I’ve always thought culture was about what people are doing when you are not looking,” says Rathie. “In these [lockdown] times, it’s still about creating a workplace culture although usually you are in the same place. Now we find ourselves in our lounge rooms and, to make sure everyone feels connected, we have to ensure good communication with the team.

“Bullying might occur online, but less so. Physical distance means I don’t think we will be seeing a lot of sexual harassment.”

Experience shows there are some crucial and overt steps needed to spell out what is acceptable in a workplace, says Rathie. Setting standards around respect is one of the key messages she gave the 2020 graduate cohort earlier this year.

“In the office, we stick the details of the EEO [Equal Employment Opportunity] officers on top of the printers for a wide range of people to see,” explains Rathie.

“The standard you walk past is the standard you accept, so you have to have the conversations and call it out.”

Craig Badings

Craig Badings

The talented and powerful must be held to account

Partnerships may be changing but they still often reward certain behaviour, which can make it tricky to take action against a high earner, according to Craig Badings, a partner at reputation risk management firm Senate SHJ.

“If someone is generating lots of income and there is an undue focus on money, that can produce certain behaviour at the expense of value and purpose,” explains Badings.

“In a firm, if the word gets out that that is the way things are done there, it doesn’t become an attractive place to work.”

A failure to tackle bullying can have a serious bottom-line impact. A major crisis which affects reputation, according to the firm’s research, means companies can lose 30 per cent in earnings per share. An estimated 85 per cent of the value of a business is intangible.

There’s a significant downside to getting these things wrong.

“Sometimes media sentiment never recovers or remains negative [towards a business] for years,” says Badings.

“Social media has meant people can record the bullying, so the game has changed but lots of companies are slow to change.”

There are three key drivers of reputational integrity: quality of products, leadership, and culture. Badings says law firm managing partners need to ask themselves, “What is the value of reputation, what do we lose, and why should we spend that money preparing for a crisis?”

Those calculations can certainly help grab the attention of senior executives and partners, who need to be visibly involved and not just paying lip service.

Every year at KWM there are seminars and panels about harassment, Rathie says. The firm makes sure that most senior people are part of that panel and the message comes from the top, including that there are consequences for bad behavior.

Sarah Crellin

Sarah Crellin

There would be a quiet legal settlement. Now we talk about it. The thing that has made the biggest difference is when someone reports we are getting an outcome – and we have sacked some managers.

Toxic behaviour must be confronted

When she started at Seven three years ago, Katie McGrath, Chief People and Culture Officer, was struck by the outdated, male-dominated culture.

“I walked into an organisation that, like most media businesses, was a bit trapped in the olden days,” says McGrath. “Seven was number one for a long time and with that came a sense of entitlement and a culture where people were used to winning.”

She started her job during a tumultuous period for the media company, which was dealing with the fallout from former CEO Tim Worner’s well-publicised affair with his former assistant, Amber Harrison.

Seven, like many mainstream media companies, was facing enormous pressure from upheaval in the sector. Culture change was essential and had to start at the top, says McGrath.

A priority was getting the agreement of the board and CEO about what kind of organisation needed to be created as advertising revenue dropped and streaming services and competitive pressure built, she says.

Tackling bullying transparently was a crucial step in transforming the culture at Seven, McGrath says. In the past, bullying wasn’t addressed and was swept under the carpet.

“There would be a quiet legal settlement. Now we talk about it. For me, the thing that has made the biggest difference is when someone reports we are getting an outcome – and we have sacked some managers.”

Two factors made the most difference, she says. The first was encouraging people to report, and helping those who thought this behaviour was normal to realise it wasn’t. Some executives, McGrath says, had never done any training and reached their seniority level by being the biggest bully in the room.

The second key factor was to begin calling out toxic behaviour and state clearly what is okay and what is not. Bystander training was also introduced, along with a management focus on ensuring employees felt safe.

“The way I argue to the board is to say, ‘It may feel onerous and costly upfront, but it’s better in the end’. If we get these things [identified] we can resolve them,” she says.

After many years of experience dealing with culture problems in professional services firms, Badings says businesses make the same key mistakes when poor behaviour arises.

“Taking no action is damaging and it actually erodes trust in their [senior leaders’] decision making, and they are seen as hypocrites. I find the biggest trap is that there seems to be a huge lack of understanding about how this erodes.”

With bullying, Badings adds, there are two key factors that raise a red flag: leaders being surprised because reporting is low due to fear from complainants that they will lose their job; and the organisation has taken the reports of bullying on board, but they have gone nowhere. He says the second issue is often the worst.

At KWM, the emphasis is on transparency and accountability, according to Rathie, which means employees should feel safe to raise problems without fear of repercussion.

“If you have a culture where people feel, if I do speak up my grievance will be heard and backed up by my partner and the process, then you don’t have the cases,” she says.

“If you have a very toxic, masculine culture, like [Harvey] Weinstein, the blokes protect the blokes and it goes on down the line. If you are culturally diverse and have women who have spoken about the need for respect, you don’t have that ladder.”

Diversity is key

Plenty of work has been done to boost gender equity at KWM, which has one of the highest female equity partnerships in the country, according to Rathie.

The firm uses a number of interventions such as anonymous recruitment, where names and other indicators are removed from job applications to ensure less bias in selection. There is support and mentoring for women and culturally diverse employees, particularly in navigating the career pipeline. But challenges remain.

“It’s been so hard to move the dial of about 23 to 28 per cent women partners for the last 10 years. We have a lot of senior women but can’t put them through. There are structural problems because they can’t reach the same level of financial contribution at that time. We need to help women through this time with structural intervention – the more women equity partners you get, the more you help.”

When McGrath joined Seven, she found she was the only woman around the board table which was dominated by “lots of male, pale and stale media types”. More diversity throughout the organisation was a core part of transforming the culture.

“It’s still my very, very strong view that you don’t get change in diversity unless you do it at the top,” she says. “We now have 50/50 gender split in the executive team. You have to make male executives voice their support and make it part of the culture.”

Newsrooms are the most robust environments, she adds, and putting women into senior positions causes a change to the dynamics.

The hallmark of a good culture is where people get fair treatment irrespective of race or gender, Rathie says. And there’s a fairly simple way to test whether that is the case.

“You know when it feels right if you look around and see old and young, women and men and different nationalities.”

Toxic cultures can be transformed, Badings believes.

“The cultures I’ve worked with over the years know they have stuffed up and are really committed to making it right. The trickish part is how far they are willing to admit a mistake – and hubris can be the problem.”

You can get trust back, he adds, but it’s about commitment and not hollow words.