Jonathon Hunyor has spent most of his life working with instruments: be it playing the trumpet in a big band or using the law as one to expose privilege and injustice in society. Being a solicitor comes with a position of power, and this is not something the CEO of the Public Interest Advocacy Centre takes lightly. The Law Society Journal gains insight into a man rarely in the spotlight.

Jonathon Hunyor draws many parallels between his 25-year long career as a social justice solicitor and his life-long passion for playing the trumpet. Hunyor, CEO of the Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC), picked up the instrument when he was in grade three at school, well before his path into law was forged. He tells the Journal it was his mother who instilled in him the concept of practising to achieve precision.

“If I was going to play an instrument, I needed to practise. That meant I developed enough technical ability to do things like improvising, which is something you can only do well when you get to a certain level of mastery. That combination of discipline and creativity is something I have learnt from the trumpet,” Hunyor says affectionately.

“When you are really improvising, you are absolutely present in the moment, you are listening to everyone, you’re responding to the mood of the room, you are out of your own body.

“When I am really on my game, I bring that to my work as well. I am present, listening and responding to what is going on. I am making music and that is super exciting.”

As a primary schooler fumbling over licks, Hunyor could never have grasped the far-reaching benefits playing the trumpet would engender in his professional career as a lawyer and as a CEO. The instrument provides a vital outlet that ensures he walks into PIAC’s Sydney office every day with a clear head, focused on leading the non-profit organisation on its mission to tackle systemic injustice and inequality by exposing the laws, policies and practices that entrench disadvantage in communities across Australia.

When his day-to-day is over, the trumpet is always there, played with assurance at “social hours” in a quiet room under his house so his family can tolerate the sound. Hunyor’s natural affinity for teamwork shines every week during rehearsal with an 18-piece jazz orchestra, a group he has been a part of since 2002.

The 50-year-old admits that at times, in his more than four decades of playing, he becomes frustrated by his “limitations” as an amateur musician. He says this mirrors a key challenge for solicitors working in social justice in that one needs to be content with making small inroads on the path to solving a bigger problem.

One of the challenges for lawyers is that we are not always great storytellers, because we tend to locate ourselves in the centre of the story. We can get better at that, and particularly at who we are telling the story about.

“There was a stage, maybe it was a maturity thing, where I learnt to enjoy the fact that for five seconds in a three-hour gig, I did something as good as Miles Davis, rather than being frustrated that I wasn’t Miles Davis the whole time,” he explains, chuckling at the reality.

“I’ve learnt to take pleasure in the brief moments of delight and beauty, rather than be frustrated at all the time I am just Jonathon Hunyor, the amateur trumpet player.

“I hope I can bring that to how I do my job.”

Hunyor has dedicated his career to social justice, specialising in discrimination and human rights, migration and refugee law, Aboriginal land rights, criminal law and coronial inquests. He previously led the Legal Services team at the Australian Human Rights Commission and was the Principal Legal Officer at the North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency (NAAJA) in Darwin.

Despite his impressive resume, Hunyor has deliberately kept himself away from the limelight, a testament to his unwavering priority of championing the communities and people he represents. Deeply humble, Hunyor takes a few deep breaths before the start of his interview with the Journal, noting that talking about his life and achievements does not come naturally to him.

“One of the challenges for lawyers is that we are not always great storytellers, because we tend to locate ourselves in the centre of the story. We can get better at that, and particularly who we are telling the story about.”

“One of the things we do at PIAC is tell the story about community, about people, about change and the impact on individuals and lives. I think that is a far more interesting and engaging story, but it requires us to focus less on what we did and our role, and more on the role of our clients and the communities that we serve.”

Playing the long game

Hunyor explains that PIAC’s remit to influence change is a blank canvas. “Public interest can mean lots of things to lots of people,” he says. But, for the organisation that Hunyor has been at the helm of since 2016, it’s about looking for ways to improve Australia’s legal system, so it works better for marginalised communities and people experiencing disadvantage.

That vision materialises in the form of test cases and strategic litigation, research and policy development, and continuous advocacy on issues like asylum seeker rights, homelessness, Indigenous justice and a fairer NDIS.

“My vision for PIAC is to ensure that it is a strong partner to community. That seems surprisingly simple. But if we can bring our expertise and power as lawyers to the issues that matter to the community, and support them to make the change they want to see, then that is where I want to be. To build trust, credibility and respect from the community, so that people come to us because they want to work with us. When we see that happening on issues like Aboriginal child protection, that is when we know we are nailing it.”

But, when asked about whether the enormity of that task gets overwhelming, Hunyor cites a poignant quote from American author Anne Lamott to explain his composure: ‘Thirty years ago my older brother, who was ten years old at the time, was trying to get a report on birds written that he’d had three months to write, which was due the next day. We were out at our family cabin in Bolinas, and he was at the kitchen table, close to tears, surrounded by binder paper and pencils and unopened books on birds, immobilized by the hugeness of the task ahead. Then my father sat down beside him, put his arm around my brother’s shoulder, and said, ‘bird by bird, buddy. Just take it bird by bird’.”

Hunyor adds: “I don’t find the need to do everything overwhelming. That is probably my mother’s influence; she was a super-practical person and was always about breaking something down and tackling it one thing at a time.

“We are trying to do something audacious across all our work at PIAC; trying to make a fairer society and tackle systemic injustice. One of the ways we can do that is by not being overwhelmed by the enormity of that challenge and working through it with discipline and focus. Bird by bird.”

Pics above: Playing a gig with the NT salsa band ‘Sabrosa’ in about 1999.

With James Morrison, the late Vlad Khusid and Richard Maplass at a tribute concert for Khusid in 2022.

Hunyor with his daughter and Speedy McGinness in 2010 at Kalkarindji. Speedy is a Kungarakun and Gurindji man Hunyor worked with as a Kriol interpreter.

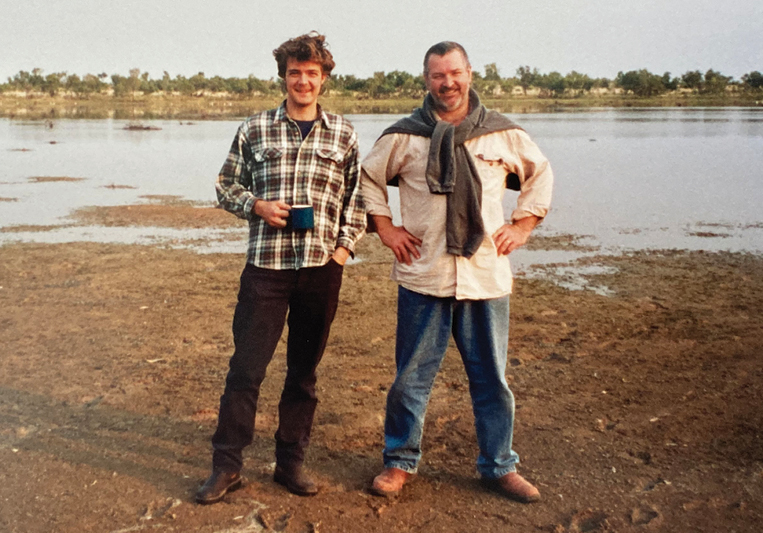

With former colleague Michael Prowse at Boundary Bore in Central Australia with the Central Land Council.

Hunyor is widely praised for his contribution to social justice law. The way he speaks about the cases he has worked on is engaging and fascinating; he never takes the credit for successes, and always uses ‘we’ and ‘us’ as opposed to first-person pronouns.

After graduating from the University of Sydney, Hunyor moved to Darwin to jumpstart his legal career away from the big smoke. He landed a gig as a crime duty lawyer with Legal Aid in the late 1990s, and quickly became involved in the campaign against mandatory sentencing in the Northern Territory (NT). At the time [1997], mandatory sentencing for property offences saw first time offenders serve 14 days; a second offence received three months, and a third landed a person in custody for a year.

“I had a client who was looking at 14 days for having broken a window at a hotel that she punched in anger. That instantly made me see the way a legal system could work unjustly. We fought hard to get change on that,” Hunyor says.

“They watered down the provisions and introduced exceptions, and then, when the Labor Government was elected in 2001, there were some reforms. But only 25 years later [in 2022] have we really seen the end of mandatory sentencing in those forms.”

Almost a decade later – after a stint as a solicitor at the Central Land Council in Alice Springs and his time at the Australian Human Rights Commission in Sydney – Hunyor returned to work in the NT as the Principal Solicitor for NAAJA. A significant part of his practice during his six years in the role involved representing, in the Supreme Court, people with cognitive impairment or mental illness who were not fit to be tried.

“When I arrived in 2010, I was handed a stack of files and told: these are really hard cases that nobody is comfortable doing and you’re the boss, so you have to do them,” he says.

“This meant seeing families struggle with a system that led to their loved ones being indefinitely detained in prison, and the lack of options to be able to get people out. We had to fight just to get people out with the support needed to live in the community, be with their family and go back to country. Those cases have really sat with me.”

Hunyor encountered one of the most memorable cases in his career during his early years in the NT. He led a case for an East Timorese asylum seeker who had come to Australia fleeing persecution at the hands of Indonesian military. The case for whether Australia owed protection obligations to approximately 1,650 people who had fled East Timor had been going on for decades, with Legal Aid NSW and Victoria successfully winning two major test cases. However, the issue had not yet been resolved, and the situation had changed with East Timor’s independence.

When you work on these issues, you have to be prepared to play the long game. I have enormous respect for the people that do. There were lawyers who worked on that refugee campaign for decades, and I came in and ran a case over [just] a few years.

Hunyor, having not long arrived in the NT, inherited a filing cabinet full of the cases of clients seeking asylum from East Timor, and shortly afterwards one of those clients was chosen to appear before a full bench of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal to effectively finalise the issue. Hunyor convinced his manager to let him fly to the war-torn country and collect witness statements from the United Nations and other NGOs on the ground. He was able to establish that, although East Timor had achieved independence and there were transitional government arrangements, it was not safe for his client to return. Hunyor and his assisting counsel won the case, and ultimately the Australian Government allowed the majority of the asylum seekers to stay.

“When you work on these issues, you have to be prepared to play the long game. I have enormous respect for the people that do. There were lawyers who worked on that refugee campaign for decades, and I came in and ran a case over [just] a few years,” Hunyor says.

“The ability to stick with an issue and take on things that are not easy is what I hope we can bring at PIAC. It is not about a quick win, and that is a real gap in the sector that an organisation like PIAC can fill. To be able to take up issues like raising the age of criminal responsibility or reforming the child protection system so that it gets better outcomes for Aboriginal kids and families. Those are long term, systemic pieces.”

Hunyor has taken the reality of practising in social justice and turned it into a lasting legal career, something he puts down in no small part to being “really clear” about what he can and cannot change.

“When I worked at the Aboriginal Legal Service at NAAJA in Darwin, I knew my role. I worked for an Aboriginal board, and an Aboriginal CEO. I had a role in policy and advocacy, but we never saw as much change as we wanted. I could not let that frustrate me, but instead what I could do was run the best legal practice so that our Aboriginal clients were getting the best quality legal service. That was incredibly rewarding.”

However, Hunyor says, accepting that change takes time in the social justice space is not easy. He sees solicitors working at organisations like Legal Aid or in community legal centres become frustrated that while they are helping individuals with their problems they never get the chance to resolve underlying systemic issues.

“Lawyers are by nature problem solvers, and that can be great. People come to us to fix things: they have a problem, and we bring an analytical mind. That is really powerful, but we almost have to check ourselves. It means not taking problems off community and saying ‘we’ll solve it, we are the lawyers, leave it with us’. We must walk with the community. That requires us to be patient, do a lot of listening and be uncomfortable. There is a cultural transformational piece for us as lawyers around that. It’s not necessarily our straight skill set.”

An engine for change

Hunyor has never had a five-year plan, and never thought he would be a CEO. While that may seem off-kilter from a traditional legal trajectory, Hunyor says it is how he developed an ongoing love of the legal profession. When he sits down with the Journal in Sydney’s Hyde Park on a bluebird summer day, he explains that longevity in law for him is about being able to uproot, grow and change.

“I really haven’t planned any sort of career. I’ve always done a job that I thought was one I’d find challenging and rewarding, and where I could contribute,” he says.

“I’ve hoped that if you do a job that you are passionate about, and you do it well, then when it’s time to move on, another opportunity will present itself. Being open to different opportunities is something that has worked for me.”

Hunyor’s entry into law is deeply relatable for many solicitors, in that there was no grand reasoning behind it. Law was a “sensible” option garnered by good grades and hard work at school.

Hunyor candidly reveals that he would love to pin his decision on a grand dream to change the world for the better, but says that would be retrofitting. “At the time, these things happen organically. You have a job, then you have another job, now you have a career, and you have to explain how you got there. Whereas I pursued what I was interested in and passionate about. I never woke up in year 6 and thought ‘I want to be a lawyer’,” he laughs.

While he was studying, the subjects Hunyor found most attractive were about people: anti-discrimination and employment law were standouts for him.

“I did critical legal studies, and really started to think through who the law worked for, and who the law didn’t work for and where we find power. I saw the capacity of the law to be an engine for change and justice. And also the law as an engine for injustice. I found that fascinating, and that was where I saw myself working.”

When asked about his upbringing in Sydney, Hunyor first describes it as “pretty unremarkable”, before stopping and changing tack: “Maybe it wasn’t unremarkable, maybe it was remarkable because I was surrounded by love and support. That made it possible for me to pursue the things I was passionate about and driven by. That is a great privilege.”

Hunyor’s father came to Australia with his family as a refugee after fleeing Hungary at the end of World War II. This, Hunyor says, had a profound impact on his father’s world view, which unconsciously flowed through to him, and is where the roots of his passion for social justice were planted.

“My grandfather was a lawyer in Hungary but came to Australia and never worked as a lawyer again because he didn’t speak enough English. He was at an age where he couldn’t retrain. He died before I was born, but I have read diaries and letters he wrote, which my father and uncle translated from Hungarian for me. He had this incredible gratitude to a country that gave his family safety after fleeing from the war and leaving everything behind. There wasn’t any sense in him of having been cheated in life or having lost this very lovely middle-class existence in Hungary.

“But the opportunity to bring his kids up somewhere safe was something that meant a lot to him. That has been passed down through my father and to me. Gratitude for the safe country we live in, and the opportunities that have been given to my family is something I very much feel.”

Understanding these familial ties, it is unsurprising Hunyor chose to move to Darwin after law school. Propelled by his interest to better understand the human rights and social justice issues that exist in Australia, Hunyor knew he needed to get out of the “Sydney bubble”.

“In a place like Darwin, the themes of the Australian story are really present in a way that I don’t feel they are in Sydney, particularly if you have grown up here and have your established networks. Darwin has that boom/bust feel of a frontier town,” he says affectionately.

“In Darwin, you feel Australia’s relationship with First Nations people and our position on the edge of the country looking to Asia, and the rest of the world. There are the issues around our relationship with the land regarding mining and farming. You see Australia’s obsession with punitive law and order approaches to social problems, and our relationship with alcohol is a very present challenge. All those big themes were a really great opportunity to expand my legal horizons.”

The Top End holds a special place for Hunyor, and he has been back almost every year since he first moved there in 1997, either to live or to visit. He earnestly encourages solicitors, at any stage of their legal career, to get out of the city and work regionally.

“Everyone has a different starting point, but to get out of your comfort zone and out of your bubble is invaluable. To broaden your experience and understanding is so important for anyone. Working remotely is incredibly rewarding if you’re interested in community lawyering and making change, being able to see things from different perspectives, being able to recognise the limitations of your own view and being able to learn to listen better.”

In Darwin, Hunyor experienced a proximity to issues and decision makers that solicitors rarely find in bigger cities. He got to know government ministers because he would see them at the local markets, or because they lived next door. His main advice for achieving a sustainable career as a regional solicitor – and for the profession more broadly – is to be disciplined about separating life and work.

“When I was in Darwin, there was a point in my drive home when I’d turn on to Bagot Road. That was the point I had in my mind to stop thinking about work,” he says.

“I could fulminate over the judge that decided against me, or the staff member complaint I had to deal with, but when I hit that point in the drive, I had to switch off so I was ready and present for my family when I got home. And that was both important for my relationships with my wife and daughter, and also for some self-care, and my own mental health. Finding ways to switch off, to have hobbies outside work, other passions and other relationships, is really important, and that is a critical part of sustainability.”

Hunyor says working in legal assistance – either in the bush or the city – is “a fantastic place to start a legal career”, but it comes with its own unique challenges.

“If you work in a large firm, you could be a cog in a large machine. Whereas the lawyers who do secondments with us at PIAC, for example, they get to see the client, draft court documents and go to court. They see the whole lifecycle of a matter and get their hands on things in a way that makes you a really good lawyer,” he says, nostalgic for his early days in the NT.

“Legal assistance teaches you a lot of important things around effective communication with people from a diverse set of backgrounds. It teaches you to be resourceful. The camaraderie and the collegiality in the sector are powerful, and are things people take with them in their career even if they don’t stay in the sector. But a lot of people get hooked because it is incredibly rewarding and endlessly fascinating.”

Leadership means making sure I have a clear sense of our strategy, that things operationally are working well, that staff feel valued and supported, that we are communicating well with each other, and then making sure that our external relationships are strong and that we are well supported by funding.

He adds: “But salaries are a big challenge. Early in your career, it is less of an issue because you are keen to get your first job and the quality of the work is really important, and also in dollar terms the gap between your salary and the salary of someone in government or in the private profession is small. But that becomes exponentially greater as you go up the scale. We rely on the commitment of people who work in the system, and their love of their work. But it is not something that everyone can sustain.”

An instrument of power

PIAC’s Sydney office is set up as open plan. Hunyor takes the Journal on a tour, and a sense of collaboration is immediately obvious as groups of staff gather at various desks, talking and staring intently at files and papers. “No corner office at PIAC, only a corner desk,” Hunyor says as he reaches his station. Hunyor does not have an example of a “typical day in the life”, only one that he says requires a constant “spinning of plates”. As a leader, he says, he aspires to create a space in which a team of great people can do great work.

“Leadership means making sure I have a clear sense of our strategy, that things operationally are working well, that staff feel valued and supported, that we are communicating well with each other, and then making sure that our external relationships are strong and that we are well supported by funding.

“I got some really good advice from Simon Rice [renowned human rights solicitor and law professor] when I got my first management job at the Human Rights Commission. He asked me how I felt about leading a team, and I said something along the lines of ‘it’s a bunch of really smart people, everyone tends to do their own thing, I think it should be okay’. He very gently suggested that was not the right way to go about it and if I was going to be a manager, I needed to make sure I was committed to that. Otherwise, I would be letting the team down.

“I really took that to heart. It is advice I often pass on and credit to Simon. If you are going to take on a management role, you need to make sure you are doing that part of your job well. Because it does not matter how well you are doing as a lawyer, if your team is not functioning well because they aren’t getting the support they need, then you are not going to be an effective leader.”

It is the people that keep Hunyor coming back to law every day – both his colleagues and the individuals in the communities he meets and represents. Although he has mostly stepped away from court work, Hunyor admits he misses the individual cases that used to light his fire. “I have to take vicarious pleasure in being able to contribute to the work we do, to support our teams to hopefully add value to cases and strategies that we develop. But some days, I wish I was arguing a case in the Court of Appeal in Darwin again,” he says.

When asked about his vision for the legal profession, Hunyor takes several moments to consider the weight of the question. When he finally answers, he says: “Greater diversity in the profession is essential.

“As lawyers we must never lose sight of who the law is working for, and who it is working against. Greater diversity in the profession will help us remain clear about that because it will mean it is not just drawn from the people for whom the law works,” he says.

“I think we all need to take seriously and be more committed to doing something about the way the law, as an instrument of power, can be part of the problem. And our role in that. That is the thing that gets me. That is always on my mind. For me, it’s a matter of being aware of power and where it lies. Society likes to think that the status quo is the natural order of things, but it is an order that has been created to maintain and uphold power. And unless we are prepared to own that, I don’t think we are being entirely honest.”