Zoom and online interactions just can’t replace interacting with real people in the classroom.

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed huge challenges for the university sector, with many law schools struggling to stay afloat as international student numbers drop off a cliff. Students were left learning from their bedrooms, dining rooms and verandahs, and attending lectures via the cloud, with all its stilted communication issues. Will law degrees be taught this way for good?

The COVID-19 global pandemic has dragged even the most reluctant academics and students into the long-mooted virtual future. Yet for all of the benefits – the widespread uptake of under-utilised technological tools, flexibility, dissolved distance between experts – the shift has highlighted a tricky and expensive truth for cash-strapped universities in the gradual return to campus.

This place? It might have hallmarks of the promised land of future legal education, but it is just as marked for what is missing.

“Zoom and online interactions just can’t replace interacting with real people in the classroom,” says George Williams, Dean of the Law Faculty at the University of New South Wales (UNSW).

“It’s exposed some of the difficulties in enabling students to develop relationships, to build team skills. We’re doing the best we can, but we’re learning the benefits of face-to-face teaching.”

In surveys, students have said they are mostly grateful for the option to learn from home; but they’re looking forward to returning to campus.

“They’re missing that personal interaction,” says Williams.

That interaction is fast approaching as states variously enter the third step of the federal government’s plan to reopen the economy, including by increasing gathering sizes and encouraging more face-to-face learning. Universities must work out how to safely run campuses ordinarily heaving with life and activity, bumping shoulders and shared surfaces; barely three months after the dramatic overnight switch to online learning.

Plans vary. Some, like the University of Newcastle, intend to return most classes to face-to-face teaching while larger lectures remain online. For others, like the University of Western Sydney, many classes will remain online as part of a gradual return. The University of Technology, Sydney (UTS) is investing in an “extensive cleaning and hygiene regime across public spaces” – something all will have to do.

George Williams, Dean of the Law Faculty, University of New South Wales

George Williams, Dean of the Law Faculty, University of New South Wales

Lifelines beyond China

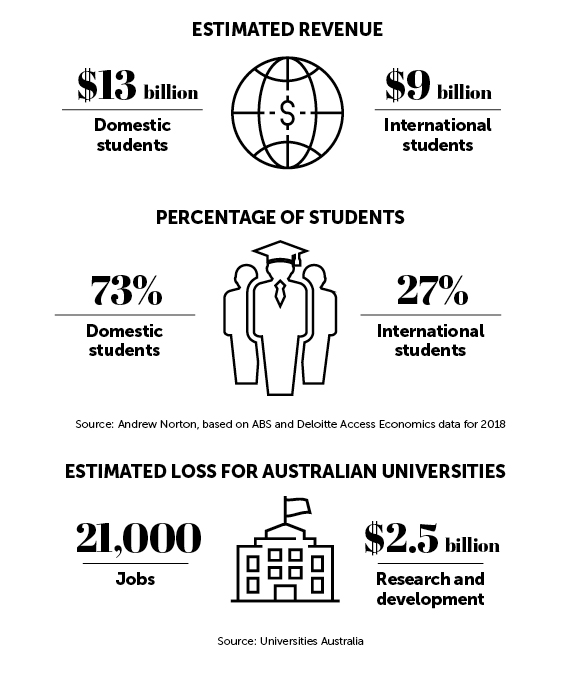

Every effort is overshadowed by the proverbial elephant on campus: nationwide, universities stand to lose an estimated $10-$19 billion in revenue over three years.

Universities Australia, the peak representative body for the university sector, warns up to 21,000 jobs and $2.5 billion in research and development could be lost this year alone. Hundreds of employees have accepted redundancies or reduced hours. At least one childcare centre has closed. Some anticipate mergers; others see that as difficult, including due to the fixed costs of physical sites.

“We’ve gone through immediate and deep cuts – no travel, lots of things – just to manage,” says Williams.

“It’s just a series of difficult, least-worst options. But you have to ask what are we here for – and that’s the students.”

Most of the sector’s expected loss is from foreign students. The Australian National University’s Andrew Norton estimates they pay an 80 per cent premium on average for their tuition and contributed an estimated $4 billion net gain in 2018. The same students financed nearly a third of university research.

Last year, Centre for Independent Studies adjunct scholar Salvatore Babones somewhat prophetically warned of this excessive reliance on overseas student income.

“The day of reckoning may not be far off,” he wrote in a detailed report. He found that more than half of the international contingency at seven prominent Australian universities was seemingly from China, contributing up to 23 per cent of revenue.

Dean of University of Sydney Law School Simon Bronitt is among those hoping Australia’s relatively good COVID performance will attract students from around the world and mitigate losses; as long as there are safe corridors of travel and efficient visa processing.

In the absence of a national rescue package for the $41 billion sector, Bronitt suspects universities will be left to their own ingenuity and global competitiveness. He is keeping foreign students connected and has prioritised diversifying the student population, a goal he has held since taking the reins in mid-2019. He is reaching out to alumni for help, including paid internships, hardship bursaries and embedded practitioners.

There are also hopes for a post-crisis surge in demand for tertiary education as people look to upskill or retrain. Sydney is among the universities considering micro-credentials: shorter, less expensive standalone courses, which could be aggregated and redeemed for a qualification.

“We have to adapt and evolve,” says Bronitt. He and his team are currently in the feasibility stage.

“It’s not this year that’s the worry, it’s next year. We have to protect ourselves as best we can.”

The trend pre-dates COVID-19, driven by a growth in demand for virtual, flexible and less formal courses.

Charles Sturt University’s provost and deputy vice-chancellor for academic, Professor John Germov, expects demand for online micro-credentials to grow and says the university is “innovating across all of its portfolios to meet the growing workforce demand for flexible study options”.

Jeannie Suk Gersen, Professor of Law, Harvard Law School

Jeannie Suk Gersen, Professor of Law, Harvard Law School

The breaking through of imperfection, messiness, sadness, and struggle might bring us all to a different appreciation of our own humanity, showing through the screen.

Lectures – not dead yet

There are concerns the crisis carries such an all-consuming urgency that universities will not have the space needed to rethink business models to improve sustainability.

“To say we might shrink, lay off casual staff – that’s not radical thinking,” says Griffith University Professor of Law and Society John Flood.

“This is a massive opportunity to recreate this and rethink what we do.”

Whatever the ideal settings are, Flood is confident lectures will not only survive, but may have a revival.

“Going online doesn’t save us from having to be social humans with physical interactions,” says Flood.

Australian Catholic University Dean of Law Rocque Reynolds says students have preferred online workshop tutorials to lectures during the pandemic, but she says it shows the need to innovate, both in technology and teaching style.

She says lectures remain “a way of passing on knowledge and love of a subject from generation to generation”. And, done well, a recorded lecture can be “more personal and engaged than a sage on a stage”. Working at the University of New England in the 1990s, online teaching involved posting reading materials and an audio tape. But students loved it.

Reynolds recalls a popular lecturer who taught there for more than 30 years.

“He’d chat away on these tapes, and he’d say, ‘The next bit is going to be really hard, so before you turn it on I want you to go and get a glass of wine and find a nice spot on the verandah’. Or he’d say, ‘Turn it off, think about these three questions, then turn it back on’.”

The gift of the COVID-19 lockdown is it has rapidly upskilled every academic – “even academics who thought they’d never want to teach online”, Reynolds quips – to use tools which have the potential to improve the learning experience. Like other deans, she credits staff efforts as remarkable.

Delivering information to students online, such as via recorded lectures, ahead of interactive face-to-face classes may bring academics closer to the engaged, Socratic-style of teaching many “still fantasise about”, says Reynolds, who admits it means reconsidering the use of lecture theatres.

In a report published in January, a group of University of Western Australia law academics suggested “flipping” the teaching model in this way could be a more “radical response” to declining lecture attendance than efforts to force busy students to come.

Reynolds wants to use technology to increase access to opportunities to develop skills, including advocacy and negotiating, bypassing the need for multiple physical rooms or prohibitively expensive travel.

At Sydney, Bronitt says the experience has released a genie, elements of which may never return to the bottle. He cites colleagues who switched from traditional lectures to 20-minute podcasts and activities ahead of a shorter interactive class.

Still, he does not believe students want “so much flexibility you’ll never need to enter the hallowed halls of the law school”.

At Charles Sturt University, most classes were already online. Mark Nolan, who became Centre for Law and Justice Director in April, says whichever mode is chosen has to be able to deliver in terms of legal knowledge, engagement, resilience and adaptability.

“The future of legal education needs to be focused on achieving those things and not on the mode of delivery,” he says.

“The difficulty is, it’s not a situation where we’ve made a pedagogical decision to provide everything online.

“People are juggling demands they have never juggled before. It’s difficult to say that the feedback is anything other than how everybody’s coping.”

Lessons in resilience

There is one common feeling among academics: exhaustion. Some work twice as long to provide content online. They worry about student equity.

One academic calls it “emergency remote learning”. They miss the classroom energy; the “hums” of agreement or “urmhs” of confusion. “It is a desolate wasteland, and it’s draining,” one laments.

Some fear administrators may streamline content to save costs.

For prospective students, some universities are relieving stress by expanding entry criteria. The ACU is working on a whole-of-school assessment; Reynolds hopes it will spell the end of “one mark” admittance. Western Sydney University is incorporating Year 11 results into its early offer program.

Current students have their own worries. About internship and job opportunities lost. About academic performance. Some universities have ditched participation marks or added a converted weighted average mark; Harvard University has a pass-fail policy.

One fourth-year student calls the experience a write off. “There’s a sentiment amongst my friends that we’ve been ripped off because of the reliance on pre-recorded lessons,” he says.

“I’ve lost a lot of access to academics. They’re not willing to take 180 email queries. It’s a sentiment shared by a lot of my friends.”

A group of parents of students at George Washington University in the United States are so disappointed they are suing for a partial refund of tuition and fees, around $USD30,000 a semester.

It’s a stressful time, but Maddocks Director of People & Culture Deborah Stonley says the use of collaboration tools like Teams could better prepare students for a virtual world.

“There’s more innovation coming into how they’re approaching their university work and assignments that holds them in good stead,” she says.

Gilbert + Tobin Capability and Development Manager Jan Christie says people shouldn’t underestimate the ability and resilience of students: those who succeed are “self-starters”.

Ian Robertson, National Managing Partner of Holding Redlich, similarly thinks the experience won’t affect the quality of prospective graduates.

“The reality of law schools is that they teach the law; what they don’t teach is how to practise law.”

Some students are relishing studying at their own pace and skipping an exhausting commute. One jokes that there are not enough cats in Zoom classes. He wants “a house tour during the break, a garden exploration, or just a check-in”.

Funny, yet his point has merit.

Writing in The New Yorker, Harvard professor Jeannie Suk Gersen says her constitutional law classes via Zoom are “strangely more intimate”.

“The breaking through of imperfection, messiness, sadness, and struggle might bring us all to a different appreciation of our own humanity, showing through the screen.”

For one Berkeley Law colleague, imperfection came in the form of their dog letting out “an enormous fart in the middle of her class on federal courts”.

Whatever happens, COVID has brought the lofty academic world into the real. Exposing real struggles, in real settings, at a time of real need – no matter how remote.