“COVID-19 has revealed the full extent to which women are still relied upon to carry the load at home. There are only so many hours in a day; if there isn’t an equitable division of work at home, there won’t be an equitable division of work in the workplace.”

When lockdowns first arrived, the enforced flexibility of working from home full-time was hailed as a game-changer for gender equity in corporate workplaces. COVID-19 was imagined to be the great leveller: an opportunity for all genders to equally share household chores and home schooling, or balance extracurricular duties and volunteering while retaining full-time jobs with flexible hours. If that has been the result, why do women still report bearing the brunt of unpaid domestic work?

Access to flexible working is often proposed as a key solution to gender inequality in the legal profession. But the forced shift to remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic has painted a more nuanced picture, as firms contemplate how to incorporate new, flexible practices for the long term.

When the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered offices and exponentially increased remote working in 2020, some workers began voicing concerns that women were bearing the brunt of increased domestic responsibilities; including extra work associated with schooling from home. These concerns echoed across social media, supported by employment data showing more women than men were dropping out of the workforce or switching to part-time work during lockdowns.

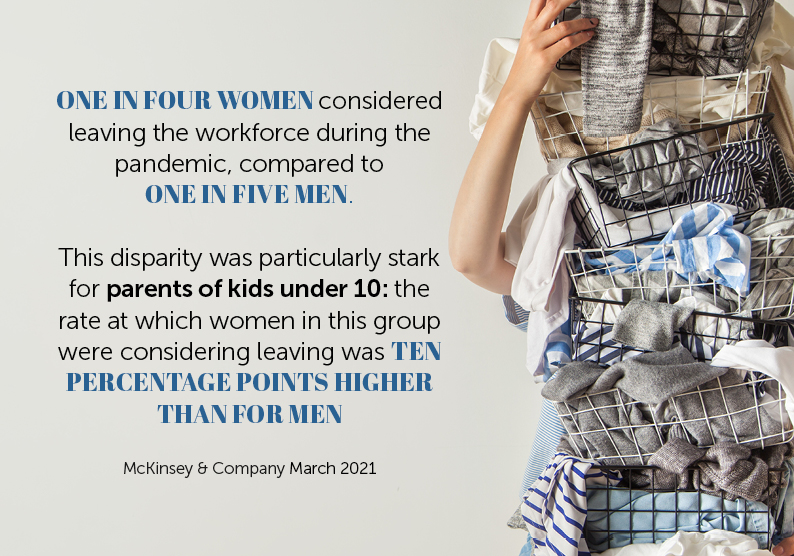

In March 2021, McKinsey & Company reported that one in four women had considered leaving the workforce during the pandemic, compared to one in five men. This disparity was particularly stark for parents of children under 10: the rate at which women in this group were considering leaving was ten percentage points higher than for men.

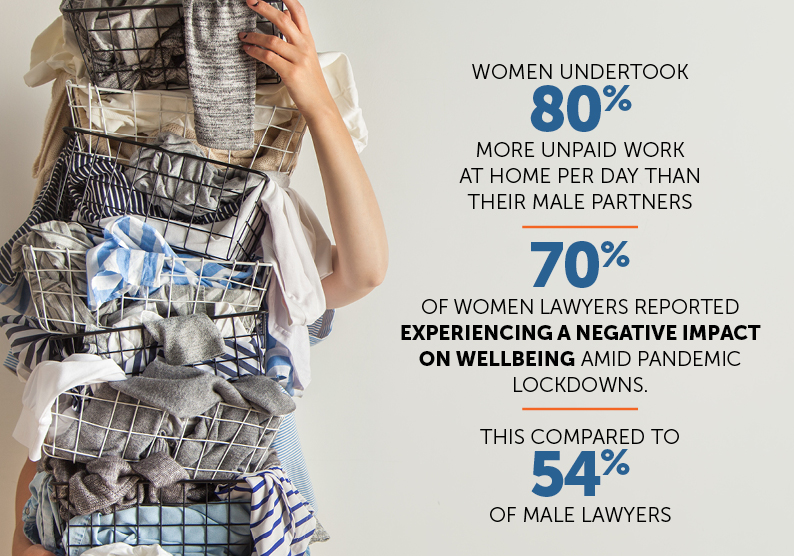

Research on the uneven distribution of domestic duties between genders prior to the pandemic, published by Per Capita in March 2020, shows women undertook 80 per cent more unpaid work at home per day than their male partners. The study notes this often came at a cost to women’s mental health and wellbeing. A more recent study targeting the legal profession, published in 2021 by Thomson Reuters Institute, reveals 70 per cent of women lawyers reported experiencing a negative impact on wellbeing induced by the “new normal” of working from home amid pandemic lockdowns. This compared with 54 per cent of male lawyers. When responding to the survey, women reported a greater increase in work hours than their male counterparts but did not report as much improved productivity as men. Women also reported taking on extra work responsibilities without pay.

Georgie Dent, Executive Director of The Parenthood and a former lawyer, says, “it’s worth noting there is not a level playing field when it comes to ‘working from home’ […] COVID-19 has revealed the full extent to which women are still relied upon to carry the load at home. There are only so many hours in a day; if there isn’t an equitable division of work at home, there won’t be an equitable division of work in the workplace.”

“Australia has had a peculiarly low female workforce participation rate, 70th in the world according to the World Economic Forum Global Gender Gap Report, for a long time despite being the top-ranking country in the world for educating women and girls,” she says. “This is because our systems and structures have not evolved to readily support women’s paid employment and COVID-19 has exacerbated this.”

Clare Murray, Founder and Managing Partner of specialist employment and partnership law advisor firm CM Murray in London, says firms took differing approaches when accommodating the increased load created by schooling and working from home.

“Some individuals asked for leave, for certain periods, some took holidays, some law firms gave extra paid leave to working parents who had these childcare commitments,” she tells LSJ. “Others gave them tremendous flexibility. It took tremendous flexibility on both parts and I think there was, for the most part, a lot of goodwill.”

She says that managers will need to be proactively mindful of hidden challenges, like increased childcare responsibilities, when reviewing performance in a remote workplace.

“Firms may risk direct or indirect sex discrimination claims as if they don’t take that into account when they assess performance and contribution when making salary, bonus and promotion decisions,” she says.

And while the approaching end of lockdowns in Australia should lead to decreased caring responsibilities as schools and childcare facilities reopen, the post-lockdown experiences of countries overseas such as Singapore, which has dipped in and out of restrictions since reopening, are a warning that such challenges may persist.

“Schools even now, in the UK, are having whole classes sent home,” Murray says. “So, there will be ongoing issues on who is going to pick up the strain of that ad hoc home-schooling. And typically, that is women.

“These are big societal problems about the sharing of childcare and eldercare responsibilities, ensuring that there’s balanced responsibility … employers shouldn’t be perceiving women as more of a burden within their workforce because of their greater share of childcare or eldercare commitments.”

The future of legal work

Despite the challenges, lawyers globally have demonstrated support for a flexible approach to stay post-pandemic. Most major firms appear to be taking the hint; with Australian firms like Herbert Smith Freehills, Baker McKenzie, Clayton Utz, Mills Oakley, DLA Piper and Ashurst offering staff the option moving forward to work from home one or two days per week without needing extra approval from management.

In the UK, which came out of its third extended lockdown in June and is a few months ahead of Australia on its journey to reopening the economy, offices have reopened and law firms are experimenting with long-term flexibility.

Murray says, “there’s a clear and consistent commitment from firms here in the UK to hybrid working,” which she says can give “lawyers of all genders the opportunity to have more of a family life, work flexibly, but also, do the networking that they need to do both internally and externally, to build their careers long-term”.

Amanda Lyras, Special Counsel at Clayton Utz and member of the Diversity and Inclusion Committee of the Law Society of NSW, believes the pandemic has reduced any negative stigma around flexible working.

“I do think that some of those former sceptics are going to be embracing this way of working, going forward, which is then going to make things easier for others who want to participate in it for family and other reasons,” she says.

In 2020, the Australian-based legal network Diverse Women in Law (DWL) ran a survey of diverse women law students to understand their experiences of COVID-19 restrictions on in-person interactions. “Diverse” was defined as inclusive of all those who self-identify as women from underrepresented backgrounds ranging from cultural diversity to LGBTI identity or disabilities.

Keerthi Ravi, DWL Founder and Board Member, says the responses were split.

“There will be instances where online engagement is favoured by women who work part-time, have lengthy commute times, or might encounter barriers to engaging in person (for example, where you might have a visual indicator of diversity), but equally there is a whole cohort of people that require in-person connections and networks to thrive in the workplace,” Ravi says.

“In our view, ‘hybrid’ options should continue being offered […] and a safe space should be created for minority individuals to speak about their lived experiences and challenges they are facing as a result of flexible work.”

Ravi emphasises that firms need to take an intersectional approach and tailor future working models to account for the array of different experiences people may face: “there needs to be some structure and guidance around flexible work models for it to work effectively”.

Otherwise, she says, team leader preferences for in-office work could have a disproportionate negative impact on “employees who need to work remotely for a range of reasons”, who are more likely to be diverse women.

Georgie Dent, Executive Director of The Parenthood

Georgie Dent, Executive Director of The Parenthood

Such concerns are backed up by a September 2021 research paper titled ‘Working from home’ by the Australian Government Productivity Commission. The report asserts: “Businesses that enable working from home, but prioritise a physical presence in the centralised workplace, could risk disadvantaging people who choose to work from home in terms of training, career development and access to promotion opportunities.”

Ravi believes “extreme screen fatigue” impacting most professional workers during lockdowns “disproportionately affects diverse women, who are juggling competing priorities: you’re working extremely long hours, juggling caring commitments, potentially living with a disability or mental health issues, unstable work etc in an industry that is fast-paced and not represented by diverse voices”.

She adds, “some of these issues are deep-rooted and trace back to systemic issues around underrepresentation in the legal profession. We need to ask questions on how we perceive success in the legal industry, what is the makeup of the legal industry and why it remains underrepresented by diverse voices.”

“We need to actively facilitate pathways to leadership, source mentors and champions and change our mindsets about productive and efficient working models.”

Invisible women?

Murray believes that so long as there’s a balance between remote working and office working, “it creates more of a level playing field for men and women, if both genders are adopting that”.

That final point is key. Dent explains, “there is a risk the gender divide will deepen if, as we recover, men return to the office and ditch the ‘flexibility’ of working from home, while women remain working from home”.

The Productivity Commission highlights potential disadvantages faced by people who work more from home than others. Its September paper warns of, “missing out on unplanned face-to-face interactions with decision makers, particularly when people worked from home intensively (more than 2.5 days a week)” and “being ‘out of sight, out of mind’”.

John Nerurker, Chief Executive Officer at Mills Oakley reflects that his firm took valuable lessons on this issue, after the experience of transitioning back to in-office working last year.

“When we were transitioning back to the office [I] heard stories of more work being allocated to those who were in the office – not through any conscious strategy, but simply because it was more convenient,” he tells LSJ. “This comes down to a question of unconscious bias and whether the way we operate is creating barriers for staff having the same opportunities.”

New challenges

According to Thomson Reuters’ Transforming Women’s Leadership in the Law: Global Report 2020, “Respondents perceived two main barriers to female advancement: the role of women at home and bias. […] more than half of the respondents referenced the internal cultural issues that cause it to be a problem. Presenteeism, lack of flexibility, and generally old-fashioned values…”.

Lyras believes flexible work has encouraged a shift from “presenteeism” to focus on output. However, Murray worries that “virtual presenteeism” – being online and available to respond to emails or instant chat – is the modern problem facing lawyers. Nerurker notes that remote workers have reported feeling overwhelmed by the sheer number of available communication channels, which lockdown has brought to a head. He says good leadership is increasingly about displaying genuine empathy.

“For example, by engaging with staff and also using the tools we have to monitor logged on time and working hours, partners can see if people are working in ways that may be detrimental to their physical and mental wellbeing which would be obvious if you were working together in the office,” Nerurker says.

In 2019, the International Bar Association’s report Us Too? Bullying and Sexual Harassment in the Legal Profession revealed devastating rates of problematic behaviour across the profession, which disproportionately affected women lawyers and were often cited as a barrier to progress. And while reduced office-based work could reduce in-person incidents, remote working is not immune to problematic behaviour. As managers have less oversight of meetings between other team members, harmful behaviour may go unnoticed.

“It’s too early to tell whether those issues are presenting more so in this remote environment than previously in an office environment,” Lyras says. “But those risks haven’t disappeared due to remote working arrangements, it’s still something that needs to be seen as a work health and safety risk.

“Perhaps there’s the potential for issues like that to take a backseat when organisations and firms are looking at how to respond to the unique challenges presented by COVID-19, but certainly they should remain on the agenda.”

It’s one of many ongoing challenges impacting gender equality in the workplace that firms must reckon with moving forward.

As the report Transforming Women’s Leadership in the Law: Global Report 2020 put it, “Reviewing and re-engineering practices and processes in key areas of the firm, including recruitment, promotion, reward, work allocation and team composition […] should be done with a specific goal of redressing the effects of unconscious bias, and it should be continual.”